Thomas Lorman - The Making of the Slovak People’s Party

Here you can read online Thomas Lorman - The Making of the Slovak People’s Party full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Making of the Slovak People’s Party

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Making of the Slovak People’s Party: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Making of the Slovak People’s Party" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Making of the Slovak People’s Party — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Making of the Slovak People’s Party" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Making of the Slovak Peoples Party

International Library of Twentieth Century History

The International Library of Twentieth Century History comprises monographs for scholars and libraries focusing on historical events of the 20th century, with a special focus on World War II and European History. The series presents original research and as such aims to widen our knowledge of the period by publishing new voices in the field.

Published

Terrorism in Pakistan: The Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the Challenge to Security , N. Elahi

Americas Forgotten Middle East Initiative: The King-Crane Commission of 1919 , Andrew Patrick

The Hidden War in Argentina: British and American Espionage in World War II , Panagiotis Dimitrakis

Women, Antifascism and Mussolinis Italy: The Life of Marion Cave Rosselli , Isabelle Richet

Historians at the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial: Their Role as Expert Witnesses , Matthew Turner

Forthcoming

Armenia and Europe: Foreign Aid and Environmental Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus , Pl Wilter Skedsmo

Censorship and Propaganda in World War I: A Comprehensive History , Eberhard Demm

The Making of the Slovak Peoples Party

Religion, Nationalism and the Culture War in Early 20th-Century Europe

Thomas Lorman

Contents

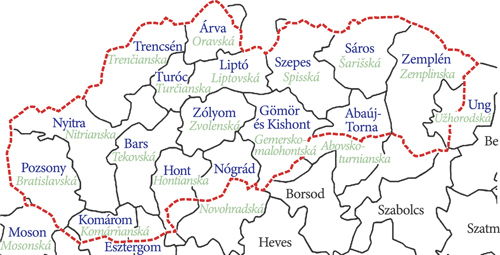

Map

Former Hungarian counties that were incorporated into interwar Slovakia

Figures

Frantiek Skyk, the first leader of the SS.

A party meeting in northern Hungary.

A caricature of Slovak nationalists attempting to be parliamentarians.

As this book has been over a decade in the making, I have depended on the help and the patience of many people. My first thanks must go to the staff of the marvellously efficient British Library in London, the staff of the National Szchnyi Library in Hungary who provided such a fruitful place to work, the staff of the Slovak National Library in Martin who went out of their way to make me feel welcome, the ever-helpful staff of the library of UCLs School of Slavonic and East European Studies and the staff of the Bodleian Library in Oxford who were always attentive and efficient. In addition, the staff of the Slovak National Archive in Bratislava, the Slovak State Archives in Byta and Nitra, the National Archive of Great Britain in London, and the Primates Archive in Esztergom, Hungary were all invaluable in promptly providing me with the materials from which this book is partly woven.

I would also like to extend my thanks to the many colleagues who have given their time and knowledge. In particular, I owe a debt of gratitude to Philip Barker, Thomas Croft, Simon Dixon, Andrew Gardner, Rebecca Haynes, Philip Howe, Katya Kocourek, Kati Lacey, Daniel Miller, rpd Poply, Martyn Rady, David Short and Trevor Thomas. I am especially grateful for the advice provided by the anonymous readers of I.B. Tauris, and the combination of guidance and patience offered by my commissioning editor which also helped bring this book to fruition.

Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends whose company over the years provided refreshment when the struggle to do justice to the topic of this book seemed overwhelming. It is for them, and especially for G and for D, that this book is dedicated.

Labelling any group of people by an ethnic category is problematic. The nationalist politicians with whom this study is concerned were convinced that all the peoples of Central Europe could be squeezed into narrow ethnic boxes. Nevertheless, defining who belonged in which box was always a contested process, riddled with generalizations and intolerant of ambiguities. The debate about who was a Slovak, and what it meant to be a Slovak, has continued throughout the past two centuries. Official statistics for the period examined in this book provide little assistance. For example, no official census prior to 1939 recorded the number of Slovaks. In Hungary, censuses in this period simply asked respondents to list their mother tongue (except practising Jews who were defined according to their religion) while censuses in interwar Czechoslovakia asked people to declare their national identity, but did not accept that a separate Slovak nationality existed.

Nevertheless, a long campaign to persuade speakers of Slovak (a branch of the Slavonic language family) that they were members of a Slavic or Slovak nation, the so-called Slovak national awakening, had achieved considerable success by the end of the nineteenth century. Even the Hungarian government accepted by that point that there was a Slovak nationality although not a Slovak or Slavic nation. In spite, therefore, of the fact that this nation building project remained incomplete in the first half of the twentieth century, for the sake of simplicity these Slovak speakers will be called Slovaks.

This book will also follow a useful convention and distinguish between Hungarian(s), when referring to the entirety of Hungarys inhabitants and state institutions, and Magyar(s) when referring to the specific ethnic group and their language. Place names will be given in the version that can be easily located on a modern map, although their Magyar equivalent will usually also be provided. As, however, the counties were abolished shortly after Hungary collapsed, their names will first be given in Magyar.

Former Hungarian counties that were incorporated into interwar Slovakia.

In the early afternoon of 14 March 1939 church bells rang out across Slovakia to celebrate the destruction of interwar Czechoslovakia and the creation of the first Slovak state in recorded European history. It was a triumphant moment for Slovak nationalists and specifically for the Slovak Peoples Party (Slovak: Slovensk udov strana , hereafter SS) which, during the previous thirty-four years of its existence, had struggled against a series of governments that had officially denied the existence of a separate Slovak nation. During this time, the SS had become the most popular Slovak party in pre-1918 Hungary and the most popular party in interwar Slovakia. Electoral success, however, occurred in tandem with a long process of radicalization. The SS repeatedly claimed that it alone had the right to represent the Slovak nation. It also incessantly denounced its opponents as a threat to the survival of the nation and the morality of the people. Moreover, the party leadership was prepared to circumvent the electoral process in order to advance its objectives. For example, in 1918, it helped break the Slovaks away from Hungary with the help of the invading Czechoslovak army, and in 1939 it helped break the Slovaks away from Czechoslovakia in tandem with the invading Wehrmacht.

A useful starting point to understand why the SS flourished within, and then turned against, both Hungary and Czechoslovakia, is the first series of radio broadcasts by party leaders that heralded the declaration of independence on 14 March 1939. The first broadcast was given by Alexander ao Mach, the chief of the propaganda office of the Slovak government, shortly after the Slovak parliament had unanimously hailed the formal declaration of independence. A brief interlude of patriotic music had not completely died away when the thirty-six-year-old leader of the radical wing of the party, who had once dreamed of becoming a priest, but had eschewed clerical vestments in favour of a jet-black paramilitary uniform, came over the radio waves. The state broadcaster had promised that Mach would bring joyful news for the entire Slovak nation, but his high, melodious voice struggled to provide sufficient gravitas. He began his broadcast by addressing those he considered his only true compatriots: Slovak men, Slovak women from the will of the Slovak nation and in the name of God, he proclaimed, we have, in the last half hour, proclaimed an independent

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Making of the Slovak People’s Party»

Look at similar books to The Making of the Slovak People’s Party. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Making of the Slovak People’s Party and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.