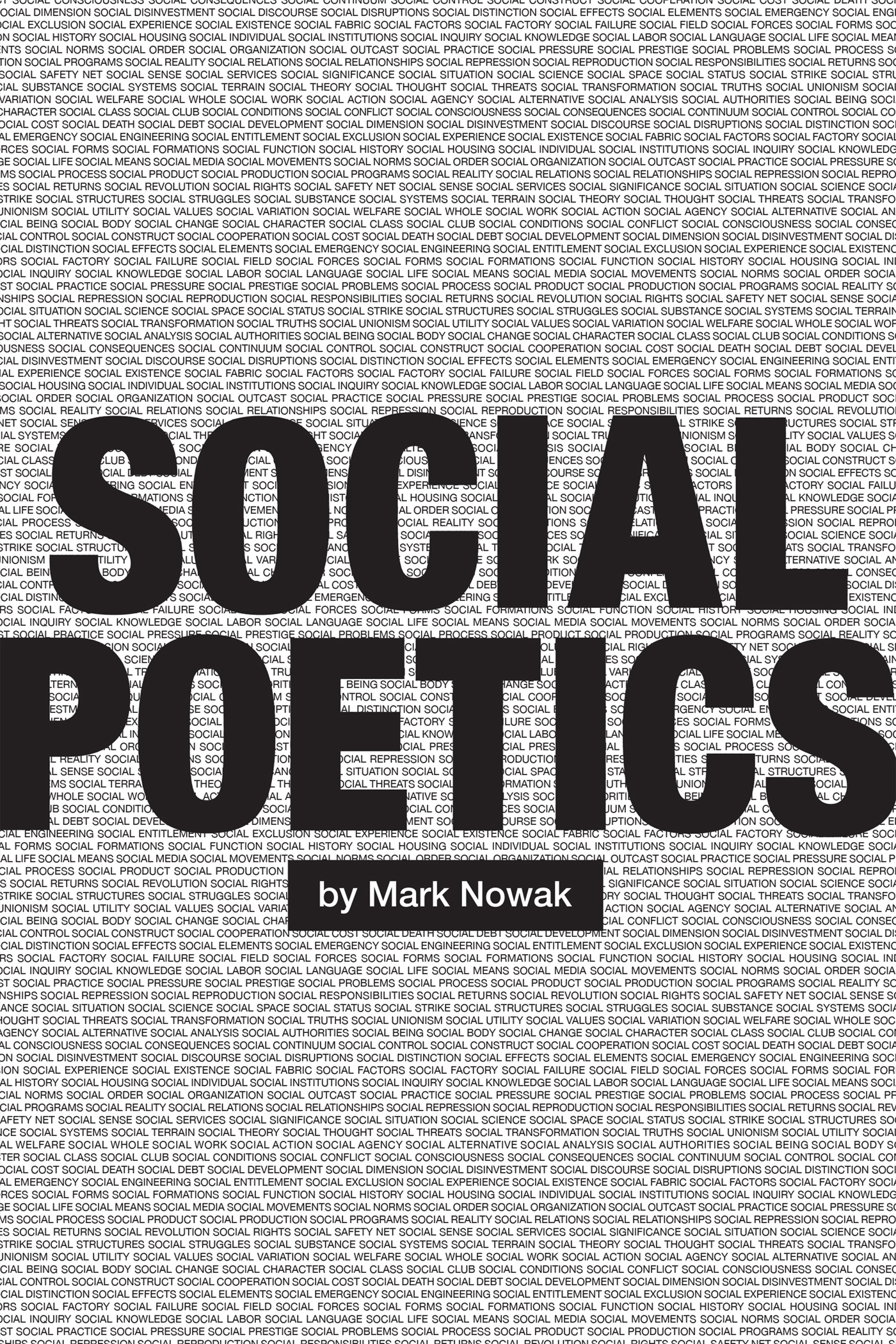

SOCIAL POETICS

Also by Mark Nowak

Coal Mountain Elementary

Revenants

Shut Up Shut Down

SOCIAL POETICS

Mark Nowak

COFFEE HOUSE PRESS

Minneapolis

2020

Copyright 2020 by Mark Nowak

Cover design by Nica Carrillo

Book design by Sarah Miner

Coffee House Press books are available to the trade through our primary distributor, Consortium Book Sales & Distribution, .

Coffee House Press is a nonprofit literary publishing house. Support from private foundations, corporate giving programs, government programs, and generous individuals helps make the publication of our books possible. We gratefully acknowledge their support in detail in the back of this book.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Nowak, Mark, 1964 author.

Title: Social poetics / Mark Nowak.

Description: Minneapolis : Coffee House Press, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019023637 (print) | LCCN 2019023638 (ebook) | ISBN 9781566895675 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781566895750 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: PoetrySocial aspectsHistory. | PoetryPolitical aspectsHistory. | Working classPoetryHistory. | Literature and societyHistory. | Nowak, Mark, 1964Political activity. | PoetryHistory and criticismTheory, etc. | Poetics.

Classification: LCC PN1081.N69 2020 (print) | LCC PN1081 (ebook) | DDC 809.1/9355dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023637

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023638

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 201 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Contents

Social Poetics

Social Poetics (An Introduction)

L angston Hughes, no doubt reflecting on his own wide-ranging political activities in and beyond Jim Crow America during the first half of the twentieth century, once described what he felt to be a central difference between the social poet and those poets who were more exclusively concerned with aesthetics and craft: I have never known the police of any country to show an interest in lyric poetry as such. But when poems stop talking about the moon and begin to mention poverty, trade unions, color lines, and colonies, somebody tells the police. Hughess crucial essay, published in W. E. B. Du Boiss Phylon magazine in 1947, is titled My Adventures as a Social Poet. Hughes describes his early poems as social poems because they were about peoples problemswhole groups of peoples problemsrather than my own personal difficulties. And, as he reminds his readers in this essay, The moon belongs to everybody, but not this American earth of ours. That is perhaps why poems about the moon perturb no one, but poems about color and poverty do perturb many citizens. Social forces pull backwards or forwards, right or left, and social poems get caught in the pulling and hauling. Sometimes the poet himself gets pulled and hauledeven hauled off to jail.

Social poeticsmy shorthand for a new formation within both literary practice and socialist political practiceborrows much from Langston Hughes. Just as he immersed himself in political organizations like the In an era when many communities of poetry continue to embed themselves deeper and deeper into elite institutions (private colleges and elite universities, costly academic conferences and writers retreats, black-tie book award ceremonies, and the like), social poetics remains a radically public poetics, a poetics for and by the working-class people who read it, analyze it, and produce it within their struggles to transform twenty-first-century capitalism into a more equitable, equal, and socialist system of relations.

Langston Hughes was, of course, far from the only poet to invoke the social in the context of twentieth-century poetry. Many might be surprised, for example, that one of the cornerstones of the U.S. poetry magazine world, the Chicago-based journal Poetry, published an issue on the social in the turbulent 1930s. While many academic scholars are no doubt aware of the celebrated objectivist issue of Poetrythe February 1931 volume, edited by Louis Zukofsky, that included work by Carl Rakosi, Charles Reznikoff, George Oppen, and othersfew readers are familiar with an issue that appeared five years later, the May 1936 issue edited by Horace Gregory and titled the Social Poets Number. The social poets gathered in this issueEdwin Rolfe, Kenneth Fearing, Josephine Miles, Muriel Rukeyser, and othersare poets who have been, except for the recent resurgence of interest in Rukeyser, largely ignored or erased from various lineages of and conversations about contemporary poetry and poetic practice. The long- and well-established literary tradition of erasing social poets and social poetics from literary traditions and canons is one of the many practices that will concern me here.

The 1930s, overall, were a watershed decade for social poetics. As Michael Denning writes in The Cultural Front, the communisms of the depression triggered a deep and lasting transformation that he calls the laboring of American culture.as writers, cartoonists, actors, musicians, and others sought to organize and unionize their workplaces. Work itself became a central subject of U.S. culture as working-class artists flooded cultural spaces previously occupied only by elites.

Writers such as Meridel Le Sueur, for example, made bold steps in the 1930s to open spaces of creative culture to working-class artists. In addition to her own novels and short stories based on working-class and communist themes, Le Sueur developed a pamphlet for the Minnesota Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1939 to help the peoples writer, the true historian create a true history of the future. Early in the pamphlet, Le Sueur implores working people, Dont tell yourself that it is not up to you to write the true history. Who is to write it if not you? You live it. You write it. She invokes the social early in her opening section, writing that language and the word are among the most social of tools. She further avows that the word as a tool is going back to the people. She urges her working-class readers to become working-class writers by getting a notebook, keeping a diary, and creating a day-by-day chronicle of their experiences. I had the title and contents of Le Sueurs pamphlet Worker Writers at the front of my mind when I created two unique working-class organizations, the Union of Radical Workers and Writers (URWW) and the Worker Writers School (WWS), groups that Ill discuss in much greater detail in later chapters.

Among poets from more recent decades, Amiri Baraka, one of my personal mentors and likewise an inspiration for my own social poetics, invokes the social in myriad forms. In the mid-1960s, the term served as the subtitle of his collection Home: Social Essays as well as the fulcrum of his thinking in one of the volumes central essays, Expressive Language. As Baraka writes in this essay, Social also means economic, as any reader of nineteenth-century European philosophy will understand. The economic is part of the socialand in our time much more so than what we have known as the spiritual or metaphysical, because the most valuable canons of power have either been reduced or traduced into stricter economic laws.

Since the 1960s, and especially during the 1970s and 1980s, Ngg wa Thiongo has consistently engaged in the practices of social poetics as I am defining them here. For example, shortly after his release from Kenyas Kamt Maximum Security Prison in 1978, Ngg compiled his prison notes into a memoir,

Next page