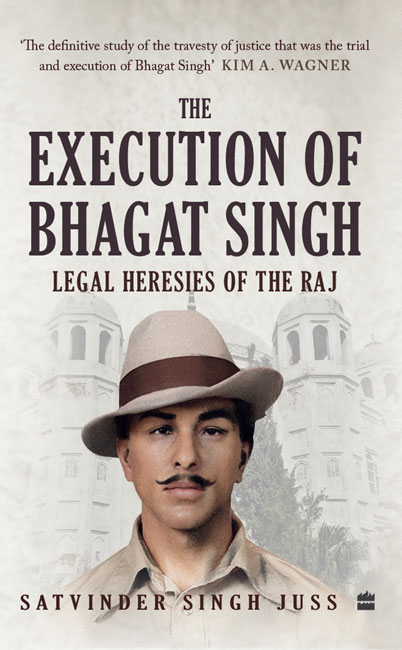

The Execution of Bhagat Singh

Here you can read online The Execution of Bhagat Singh full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Execution of Bhagat Singh: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Execution of Bhagat Singh" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Unknown: author's other books

Who wrote The Execution of Bhagat Singh? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Execution of Bhagat Singh — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Execution of Bhagat Singh" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Khush Raho Ahle Watan,

Hum toh Safar Karte Hain

Stay contented,

And pay no attention to my plight, my countrymen,

for I am but a traveller in this world,

Who now leaves you to pass on to the next.

Bhagat Singh, shortly before his death

To my parents

We are sorry to admit [that] we who attach so great a

sanctity to human life, we who dream of a glorious future,

when man will be enjoying perfect peace and full liberty,

have been forced to shed human blood.

The Hindustan Socialist Republican Association

4 June 1929

Across India today, and largely ignored in the West, the largest labour protest in human history of 125,000 farmers has been taking place. It is in retaliation to the three laws on agricultural marketing designed to alter its structural basis, passed by the Modi government on 5 June 2020, with a view to modernising Indian agriculture by opening it up to market forces. By the fourth week in December 2020, thousands had occupied several kilometres of the Tikri border between Delhi and Haryanas Bahadurgarh. As their ranks were fortified, Punjab and Haryanas new-found cultural unity was even expressed in musical performances, such as that of the Haryanvi raginis, dedicated to an Indian freedom fighter by the name of Bhagat Singh, a man barely known in the West, but reported by India Today magazine to be the greatest Indian, ahead of Gandhi and Nehru.

That his name should be on the lips of everyone is not surprising. Bhagat Singh was born in the cauldron of revolt and revolution. His birth was auspicious. As he was arriving into this tumultuous world on 27 September 1907, his uncle Ajit Singh was just returning home after being released from prison. He had made a fiery speech on 23 March 1907 at a farmers meeting in Lyallpur, where he had asked the masses to prepare for a no-revenue campaign, protesting the Punjab Colonisation Bill 1906, which, like the present-day farming laws, was designed to modernise farming. Yet, within five years the Colony Act 1912 had abandoned state-controlled supervision of progressive cultivation. So, in 1907, with her family of Ghadarites reunited, his grandmother had much to be pleased about. She accordingly nicknamed the new-born Bhagonwala (the Blessed One).

But Bhagat Singh was Bhagonwala in one respect only. He was a daring witness to the travails and tribulations of his nation at close hand. Bhagat Singh was twelve years old when the Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre took place in 1919; when the colonial government passed the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act 1919 (the Rowlatt Acts) allowing political trials to be conducted in the absence of a jury; and when the Punjab Rebellion occurred in 1919. He was fourteen when the Nankana Sahib Gurdwara Massacre took place in 1921 and scores of pilgrims were murdered by government-appointed priests for demanding democratic control of their places of worship. He was not quite fifteen when he enrolled in the National College in Lahore in 1921 and was taught from English books by radical socialist teachers like Bhai Parmanand, Principal Chhabil Dass and Professor Jayachandra Vidyalankar, who introduced him to revolutionaries like Sachindra Nath Sanyal.

From that point Bhagat Singhs destiny was marked out. Bhagonwala had his revolutionary fervour fashioned on the anvil of Indias most traumatic events in the build-up to Independence. He left National College in 1924 without graduating and joined the newly formed Hindustan Republican Association. On 17 December 1928, at the age of twenty-three, he shot and killed a British official, J.P. Saunders, mistaken for his boss, J.A. Scott, the superintendent of police, who had been in charge when nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai was lathi-charged and injured by police batons in October 1928 while protesting against the Simon Commission, which wanted to delay self-rule for Indians. When Lajpat Rai succumbed to his injuries in hospital on 17 November 1928, his death at the hands of the Punjab police gave rise to a new round of political violence, and inspired Bhagat Singh to set out to avenge his death. It became the event that transformed the political landscape of India.

After he was arrested on 8 April 1929, Bhagat Singh and twenty-five other accused were tried in the Lahore Conspiracy Case in 1931 in one of the British Empires most controversial trials. As the trial began on 10 July 1929 before Rai Sahib Pandit Sri Kishen, a regular magistrate, the 1929 Manifesto of the Hindustan Socialist Republic Association (as it was then known) proclaimed that Revolution is Law, Revolution is Order and Revolution is the Truth and that the youths of our nation have realised this truth. Bhagat Singh and his fellow revolutionaries would walk into court with clenched fists thrown into the air amid shouts of Inquilab Zindabad (Long Live the Revolution).

The call for revolution was not, however, to be misunderstood. It was not a single event. Nor was it necessarily violent. What it represented was an eternal, everlasting and permanent search for renewal and revitalisation of the present. After the trial had run for ten months, during which some two hundred witnesses had been called, Governor-General Lord Irwin decided that the proceedings should be transferred to a Special Tribunal. He signed off from the hills of his residence on 1 May 1930 the Lahore Ordinance III of 1930, even though a condition for doing that under section 72 of the Government of India Act was that there had to be an Emergency, and the Ordinance had to be for the peace and good governance of India or any part of it. This was not fulfilled. The three-judge Special Tribunal, which sat to hear the Lahore Conspiracy Case on 5 May 1930 in Poonch House in Lahore, did not allow the 457 prosecution witnesses to be cross-examined, and even though two of the three judges had been sacked two weeks later, a verdict of death was returned within five months, in October 1930. On 23 March 1931, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were hanged in Lahore Jail. The year 2021 will mark the ninetieth year since their deaths. It is a time when India faces yet more soul-searching about what it is and what it was meant to be, and whether it is headed in the right direction.

Independent India has not honoured Bhagat Singh and his fellow revolutionaries like it has others. Too often his legacy has risked being consigned to oblivion. As early as 1949, Congress politician and Bhagat Singhs one-time lawyer Asaf Ali lamented in a Pune newspaper how only a few years earlier Bhagat Singh had been a household name but now stood to be a page of history which has grown dim. Thirty years later in 1978, G. S. Deol also wrote how Bhagat Singh risked being seen only as freedom fighter and how this would do injustice to the work of this great son of India.

Today, when India is caught in the throes of ethno-nationalist politics as never before, retired Indian Supreme Court Justice Markandey Katju recently lamented how [t]he path of Gandhi and his associates like Nehru, Patel, etc. resulted in parliamentary democracy, which in India really means appeasing and appealing to caste and communal vote banks. For him, [c]asteism and communalism are feudal forces which must be destroyed if India is to progress, but parliamentary democracy further entrenches them. It is in this way that the path of Gandhi and his associates continues to divide India on caste and communal lines, whereas if we had adopted the path of Bhagat Singh we would have become united in our struggle against poverty, unemployment and other evils, and like China emerged as an industrialised and powerful nation, with our people enjoying decent lives.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

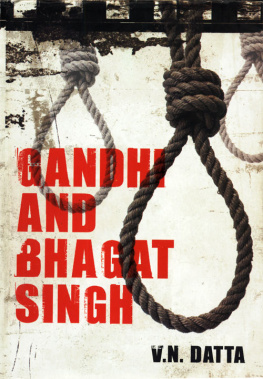

Similar books «The Execution of Bhagat Singh»

Look at similar books to The Execution of Bhagat Singh. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Execution of Bhagat Singh and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.