Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For

Peggy, of course

and for

Geoffrey and Ursula, Kathy and Rick

and for

Julia, Maggie, Anna, Coles, and Emily

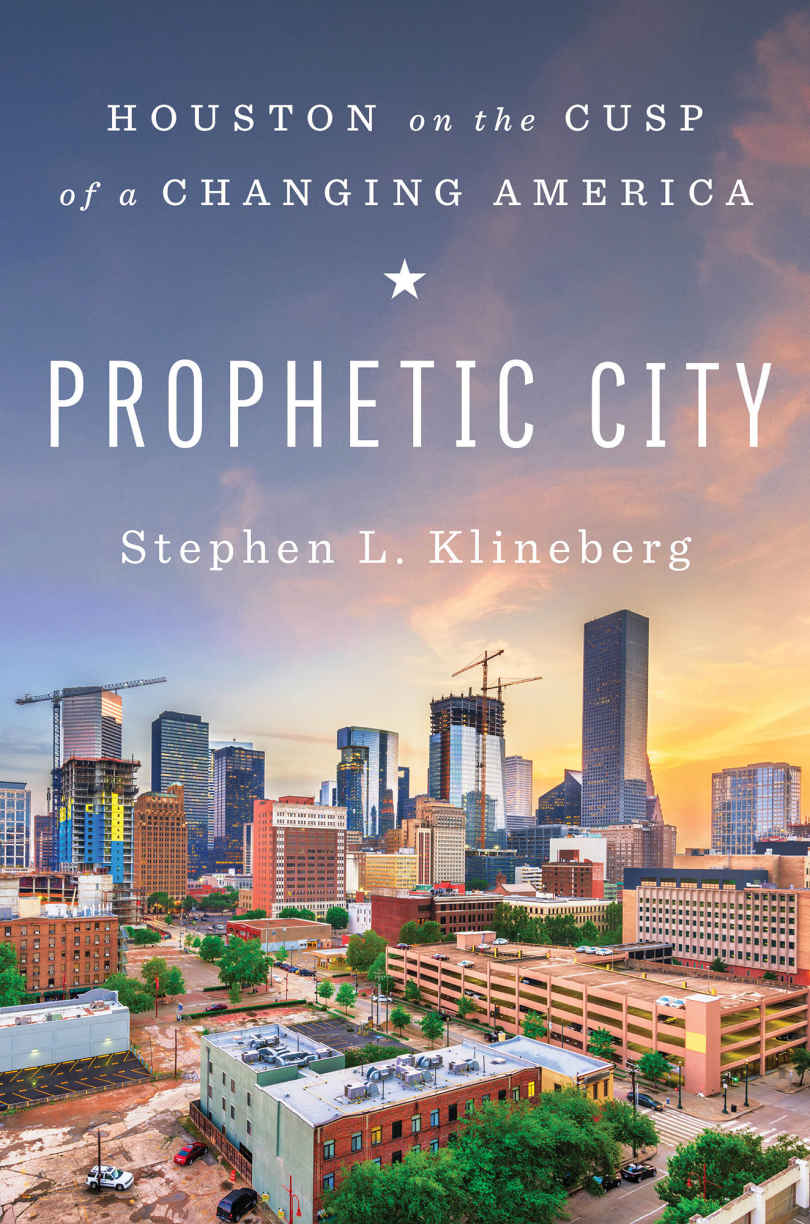

Authors Note

H ouston, Americas fourth largest city, has been largely ignored as a subject of thorough study for the better part of the last thirty years. The two most recent comprehensive analyses of the city were published in 1988 and 1991 (Feagin, Free Enterprise City; Thomas and Murray, Progrowth Politics), and both have long been out of print. This book renews Houstons claim to serious national attention.

In the spirit of nearly forty years of collectingthrough systematic survey researchthe thoughts, feelings, and attitudes of Houston-area residents, we have allowed the voices of Houston to drive the writing of this book. We have interviewed dozens of people whose perspectives have greatly enriched the narrative, and we sincerely apologize to those many other worthy voices whose perspectives we were unable to include. When requested, we have changed names and identifying details.

The experiences we have recorded here exemplify both the remarkable changes that are underway across America and the ongoing efforts to address effectively todays most critical challenges. It is not yet clear how the general public, either in Houston or in the nation as a whole, will ultimately respond to the new realities that are refashioning the political and social landscape across the nation. What is clear is that those cumulative responses will determine the future of this city, state, and country as the twenty-first century unfolds.

PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

CHAPTER 1 Getting to Houston

Men resemble their times more than they do their fathers.

Arab proverb

I am not a native Houstonian, nor did I ever travel to Texas until I went there to teach as a college professor. I grew up near New York City, the youngest of three children, and I was raised as a Quaker, a religious tradition that has continued to be an important influence in my life. I spent parts of my childhood in So Paulo, Geneva, and Paris. I majored in psychology at Haverford College, and received a masters degree in clinical psychology (psychopathologie) from the University of Paris and a PhD in social psychology from Harvard. I taught for a time at Princeton.

My path seemed set: Life would be lived along the Northeast corridor, somewhere between Philadelphia and Boston, with occasional stints abroada traditional Yankee destiny. But in 1972, I landed as an associate professor at a university I had known by reputation only. It was in a city I had never thought much about and where I surely would never have chosen to live. Yet it would turn out to be a perfect setting for the research trajectory I was on, an intriguing window into the changes that were occurring across America.

From the beginnings of my life in academic research, I have been intrigued by questions about the psychological impact of social change, the shifts that take place in peoples attitudes and self-perceptions as they respond to (or resist) the new realities. During the thirty years of broad-based prosperity in the United States after World War II (19451975), the experience of profound social change seemed to be happening somewhere else. Most American social scientists thought Western societies had basically arrived at a new plateau, and all the rest of the world was trying to become as much as possible like the worlds developed countries.

The nations of the First World were showing to the Third World, Karl Marx had claimed, the face of their own futures. So if you wanted to study social change during those halcyon postwar years in America, you needed to go to countries where older civilizations were colliding daily with the new realities of the twentieth century and trying desperately to reinvent themselves in order to succeed in the modern world.

In 1969, a yearlong fellowship from Princeton gave me the opportunity to explore these questions in Tunisia, on the North African Mediterranean coast. Led by the enlightened dictatorship of Habib Bourguiba, the traditional Arab culture was being challenged daily by the widespread determination to build a modern country. Working closely with Tunisian colleagues and graduate students at the University of Tunis, we conducted a systematic survey of families with teenage children living in the inner city, asking both the adolescents and their parents in face-to-face interviews about their assessments of the present and their perspectives on the future.

There is a well-known Arab proverb that I heard many times during that year in Tunisia: Men resemble their times more than they do their fathers. I watched this prophecy come to life in the perspectives of the younger generation of Tunisians: They were coming of age in a profoundly different world from that of their parents, far more comfortable with new ideas and new people, and feeling at home in the wider world beyond the closely guarded one in which they had grown up. Meanwhile, their parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles were having much more difficulty accepting the new social order and its challenge to traditional assumptions. One generation wanted to turn back the clock, while the other was eager to embrace the future.

Returning home in the summer of 1970, I saw America undergoing its own dramatic transformation. The country was being torn apart by Vietnam War protests, radical changes in sexual mores, and growing concerns about the environmental and social costs of rapid economic growth. You could already see the early signs that the well-paying, low-skilled, blue-collar jobs and the broad-based economic prosperity they had generated during the years after World War II were beginning to disappear, portending the Rust Belt decline of the 1980s.

Moreover, after four decades of Americas doors being closed to all but northern Europeans, immigration was back on the agenda, bringing intimations of a demographic transformation, with America just beginning the epic transition that would make it progressively less European and more Hispanic, African, Caribbean, South Indian, and East Asian. It no longer seemed necessary to go abroad if you wanted to gain a deeper appreciation of the human dimensions of social change.

The American nation, as it grew from a few settlers in the northeastern colonies, had absorbed cultures from many older (predominantly European) worlds as it spread across the continent, becoming vast and complex both culturally and politically. Using the arbitrary state lines to try to make sense of the way the countrys various economic and cultural characteristics are distributed across the continent would turn out to be an exercise in frustration. In 1981, while putting together a series of articles on American values, Washington Post editor Joel Garreau ran into exactly this problem.