Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

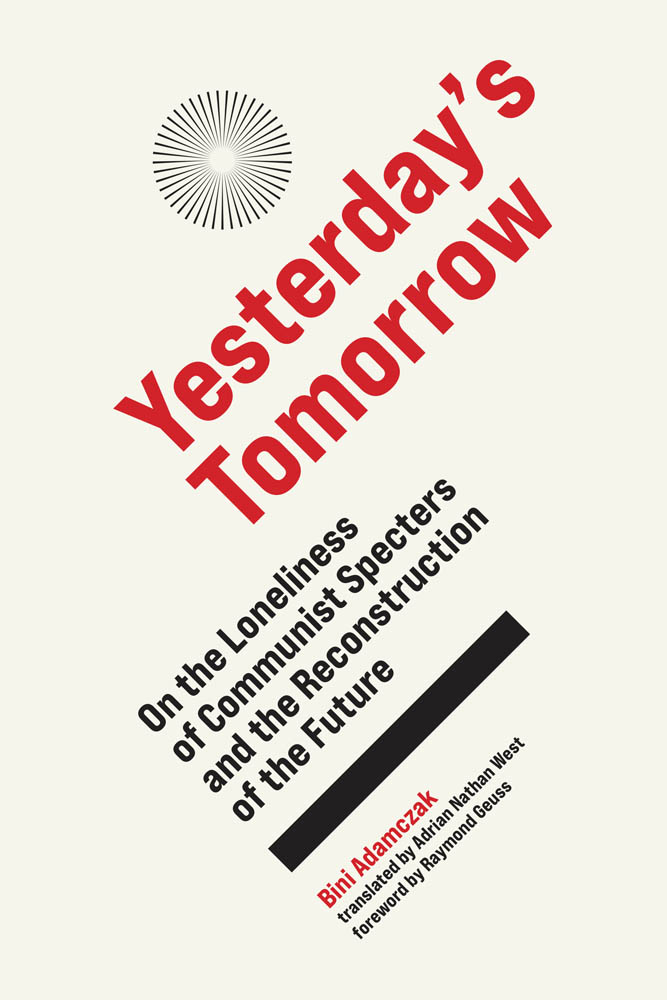

Yesterdays Tomorrow

On the Loneliness of Communist Specters and the Reconstruction of the Future

Bini Adamczak

translated by Adrian Nathan West

foreword by Raymond Geuss

The MIT Press / Cambridge, Massachusetts / London, England

2021 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Originally published in 2007 asGestern Morgen: ber die Einsamkeit kommunistischer Gespenster und die Rekonstruktion der Zukunft(c) edition assemblage & Unrast Verlag 2011.

Foreword by Raymond Geuss originally published inRadical Philosophy186 (2014): 5859, Radical Philosophy Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Adamczak, Bini, author.

Title: Yesterdays tomorrow : on the loneliness of communist specters and the reconstruction of the future / Bini Adamczak ; translated by Adrian Nathan West ; foreword by Raymond Geuss.

Other titles: Gestern Morgen. English

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, 2021. | Originally published in German under title: Gestern Morgen. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020021696 | ISBN 9780262045131 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: CommunismHistory. | CommunismSoviet UnionHistory. | Soviet UnionHistory1917-1936.

Classification: LCC HX40 .A48513 2021 | DDC 335.43dc23

LC record available athttps://lccn.loc.gov/2020021696

d_r0

WE WHO WANTED TO PREPARE THE GROUND

FOR FRIENDLINESS

How much earth will we have to eat

With the taste of our victims blood

On the way to the better future

Or to none, if we spit it out

Heiner Mller,Werke 1: Die Gedichte

Contents

Foreword

This is a book about communist desirethat is, about the deep-seated moving force within people that impels them to strive to give their lives self-chosen collective meaning by opposing oppression and arbitrary coercion, abolishing hierarchical structures, and ending the various forms of alienation. The attempts to act on this desire in the twentieth century were a series of colossal and catastrophic failures. What took place in the huge region of Eurasia that was once organized as the Russian Empire and then became the Soviet Union between 1917 and 1939 provides an instructive instance of the way in which utopian hopes, energies, and aspirations can turn against themselves, becoming more destructive the more well founded and disciplined they seemed to be. How, in the face of this, can it be at all reasonable even to try to keep any kind of grip on the utopian contents of communist desire?

Part of the answer, Bini Adamczak argues in this book, must lie in a reflection on the history of the failures of the communist project in the twentieth century. We can only reasonably hope to retain and cultivate a communist desire for a utopian future if we understand the nature of past utopian desires and the specific ways in which they failed. Each of a series of chapters in Adamczaks book is devoted to exploring one historically concrete situation in which this failure became manifest: the HitlerStalin Pact, the Great Terror of 19371939, the failure of the Left in Central Europe to stop the advent of National Socialism, Joseph Stalins rise to power, and Kronstadt. Adamczak puts particular emphasis on the way in which agents in the past did or did not realize while it was happening that their commitments were turning against themselves, transforming them into their opposite, and becoming destructive. The failures, the author holds, are real failures, and although much can be said about how they are to be best understood, nothing is to be gained cognitively, morally, or politically by closing ones eyes to them, pretending they did not occur, or trivializing them. It is also essential to the future survival (or revival) of hopes for a better future that the work of understanding and mourning be completed in such a way as not to give succor to those who would systematically root out communist desire.

The order in which the failures are presented and discussed in Adamczaks book is the reverse of the historical order in which they occurred (the HitlerStalin Pact first; Kronstadt last). This is part of a conscious strategy of the author, who thinks that those who broadly share the ideals and aspirations of the major agents and victims in this story have a natural tendency to think of the history of this period in this way, looking back from the present and locating at some point in the past a moment of unmitigated good that however passed, was lost and then initiated a historical process of degeneration. The natural question to ask is, Where and when did it go wrongwhen Stalin signed the pact with Adolf Hitler, or already in 1933, or with Kronstadt? Part of the point of the book, as I understand it, is to reject this as the right way to understand and come to terms with what happened. There was never a single moment in the past in which an aboriginally pure revolutionary will or unsullied communist desire was fully present and on the point of realizing itself, which then passed, was lost, and was perverted or corrupted. When you peel the layers of the historical onion back, you come not to a pure onion at the heart but to nothing. This does not mean that an onion is not an onion, or that nothingness is the core of the onion, but rather just that one must think about the onion in a different way.

Although the above description may give the impression that this is a book of history, it is in fact a particularly admirable feature of the book that it does not fall into any of the usual categories. If I had to describe it, I would say it is a lyrical and philosophical reflection on history in the service of a rekindling of utopian desire. Lyrical is not a word that is automatically associated with sober analysis, realism, or scholarship. This work has all those virtues, but also a remarkable lightness of touch, and an unsentimental ability to enter into the mental and psychic worlds of those who are now dead and present their world (including the nonworld of their unfulfilled aspirations) in a way that retains its full human vitality. Real historythe story of what did happenand the history of utopian desirean account of what people at any given time thought ought to happenare not only compatible but also require each other if we are to retain any hope for the future at all.

Raymond Geuss

1End

In every generation there must be those who live as if their time were not a beginning and an end, but rather an end and a beginning.

Mans Sperber,Wie eine Trne im Ozean

The last warm rays of the sun expire. Not a single bird takes off from the leafless trees, not a single wing beat can be heard. As if they have forgotten the point of flying, have lost the faith in being borne up by the air, the creatures perch on the slender branches. Slowly the long shadows of the telegraph poles, once meant to connect a continent to come, retreat in the harvested fields. The odd forgotten blade of grass waits motionless in the windless early dusk, in the distance scattered woodlands mingle with border villages history has forgotten. Its getting dark.