Joseph Maran - Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce

Here you can read online Joseph Maran - Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Oxbow Books Limited, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

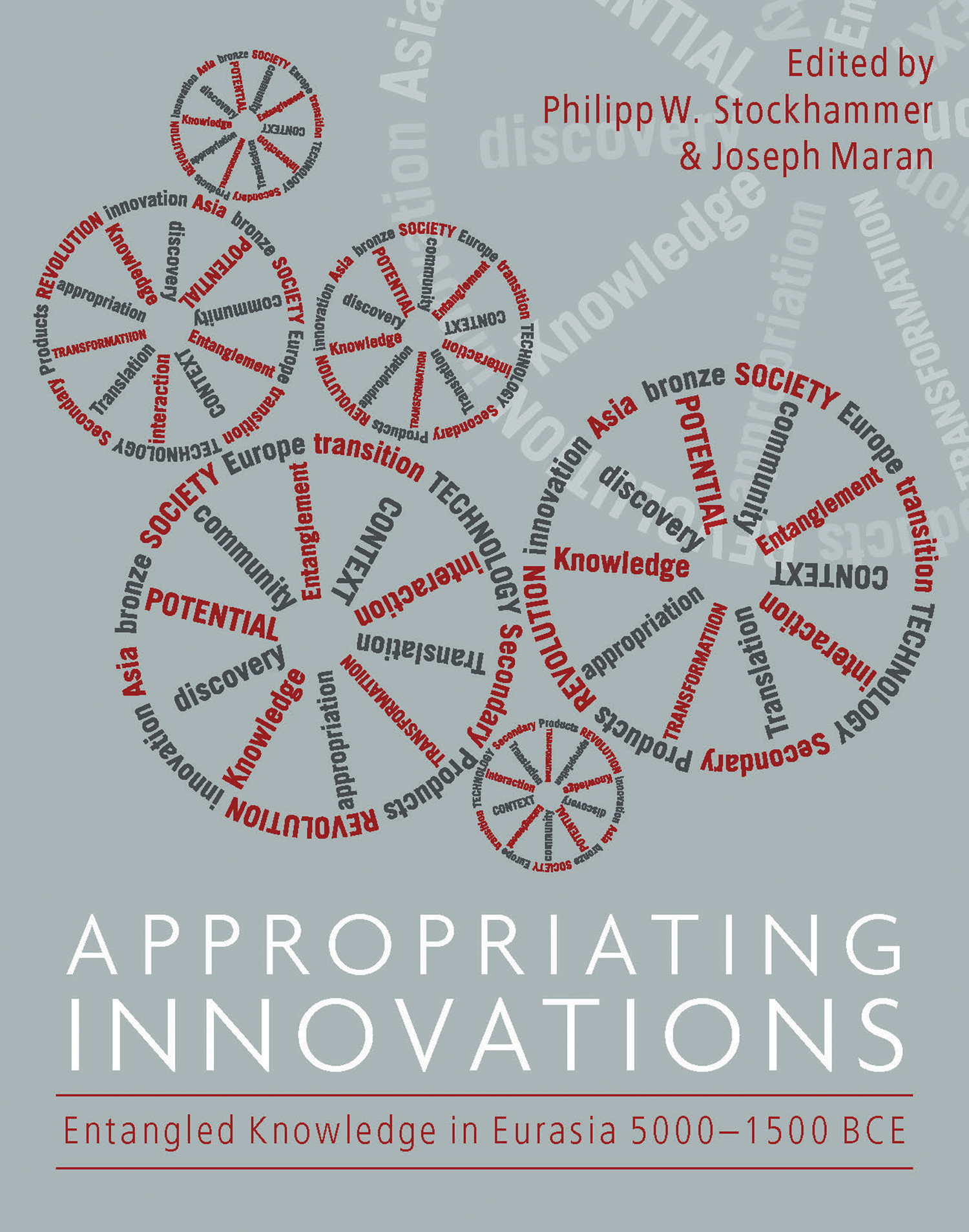

- Book:Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxbow Books Limited

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Joseph Maran: author's other books

Who wrote Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

E NTANGLED K NOWLEDGE IN E URASIA , 50001500 BCE

Edited by

PHILIPP W. STOCKHAMMER AND JOSEPH MARAN

Published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the individual contributors 2017

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-724-7

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-725-4 (epub)

Mobi Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-726-1 (mobi)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINGDOM

Oxbow Books

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

Email:

www.oxbowbooks.com

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Oxbow Books

Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

Front cover: Wheels of Innovation, Jelena Radosavljevi

The question of how to conceptualise the role of technological innovations over the last 12,000 years is of crucial importance in understanding the mechanisms and rhythms of long-term cultural change in prehistoric and early historic societies. Although the accelerating force of the advent of agriculture and sedentary village life during the early Holocene is widely acknowledged, the changes that have come about since then have often been modelled as gradual and linear. Already back in the 1920s such an approach was challenged by Vere Gordon Childe (1925; 1929), who insisted on the importance of technological and economic innovation coupled with human mobility and communication between societies in Asia and Europe in triggering periods of upheaval that he envisaged as revolutionary in their consequences. Childe was rightly criticised for his belief in teleological progress and his oversimplified idea of diffusion as an almost natural force spreading from a few civilizational cores in the Near East and Egypt to peripheral areas. Yet, his ideas were ground-breaking in their emphasis on coupling societal change with interaction and technological innovation.

It is not the aim of this volume to develop a non-linear perspective for the large number of technological innovations that have shaped human existence since Childes Neolithic Revolution. Instead, we focus on two major clusters of innovation, namely the Secondary Products Revolution (Sherratt 1981) and bronze casting. What the introduction of the Secondary Products Revolution and of bronze casting have in common is that, roughly until the 1980s, they were mostly addressed with explanatory frameworks that relied on the concept of diffusion. In the early 20th century, diffusionist thought was a very potent factor in the emergence of what was later called Kulturkreislehre and soon became the most influential current of culturehistorical ethnography in German-speaking academia (Trigger 1996, 235241; Rebay-Salisbury 2011). Its proponents aimed to distinguish cultural circles by charting the distribution of certain aspects of social structure, material culture, technology, language, religion, music and myth. These circles were believed to be so definitive that even similarities in the form of specific cultural traits between extremely distant regions were regarded as meaningful and used to reconstruct cultural origins by unravelling sequences of diffusion or migration in space and time. The Kulturkreislehre introduced the concept of diffusion to archaeology. Its most influential champion was Vere Gordon Childe.

In the 1970s, archaeology understandably tried to rid itself of the influence of diffusionism and to develop new approaches explaining the appearance of similar cultural traits in different areas. Unfortunately, this quest for new approaches sometimes led to a wholesale abandonment of the study of intercultural contacts, replacing it by explanations rooted in the notion of independent, autochthonous development in various regions. Only in the last decade have new approaches emerged that aim to overcome the division between diffusionism and autochthonism. It was in line with this recent line of thought that we designed the conference Appropriating Innovations (1517 January 2015, Internationales Wissenschaftsforum Heidelberg) on which the present volume is based. The aim of the conference was to map out alternatives to the impasse that research on the introduction of innovations in early societies had manoeuvred itself into by opting either for diffusionism or autochthonism, that is either for unidirectional flow from a few civilizational cores towards peripheral areas or polycentric invention occurring independently in different areas.

One of the most critical flaws of diffusionism was its obsession with questions of origin. It emphasised the importance of clarifying when and where an innovation was first discovered. The question of why such innovations were taken up by other societies never occurred to proponents of diffusionism, who held it to be self-evident that, once the practicability of an innovation was proven, it would automatically be adopted by other societies because it was so useful. In contrast to previous research, we set out to shift our perspectives away from diffusion and towards the concept of translation. To accomplish this, the discussion of innovations in archaeology needs to gravitate away from a focus on when and where they were developed and towards an investigation of how these innovations were ingested by societies and how this affected the lives and worldviews of the people constituting them. In this context, it is particularly interesting not only to address the question of what societies did with innovations, but especially to deal with the dialectically related question of what innovations did with society (Maran and Kostoula 2014).

During the first period of the Heidelberg Cluster of Excellence Asia and Europe in a Global Context from 2008 to 2012, our research focused on the local appropriation of objects coming from faraway places. At the Materiality and Practice conference in March 2010 our chief concern was with the transformation of functions and meanings of objects and related practices in contexts of intercultural encounter (Maran and Stockhammer 2012). Since 2012 our focus has shifted from objects to innovations, but it is still the process of translation and appropriation of what we archaeologists define as foreign that lies at the heart of our research. Nevertheless, the transfer and translation of innovations requires different forms of intercultural contact than the transfer of objects: objects can be exchanged without any instructions for use and sometimes develop their transformative potential especially when the recipient lacks any further information. The objects are appropriated, which is why our analytical focus has been on the transformative powers triggered by individual actors interaction with objects of distant provenance. From a conceptual point of view, however, such objects can hardly be translated as the notion of translation implies and even emphasises reaching out (Fuchs 2009) in the sense of acquiring knowledge about, and from, actor(s) from a long way off and creating local knowledge within this process of negotiation with the other. Innovation transfer requires personal contact and an exchange of ideas and knowledge in the framework of encounters with people from faraway places. As every technology is socially constructed, not only technological knowledge is exchanged in the context of these personal encounters, but also non-technological knowledge, i.e. ideas and world-views connected with the innovation in question. Unlike the exchange of objects, the exchange of innovations is always connected with an overspill of information about foreign world-views that hinders rather than enhances acceptance and appropriation, as not only technological but also non-technological knowledge has to be translated into individual world-views.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce»

Look at similar books to Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Appropriating Innovations: Entangled Knowledge in Eurasia, 5000-1500 Bce and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.