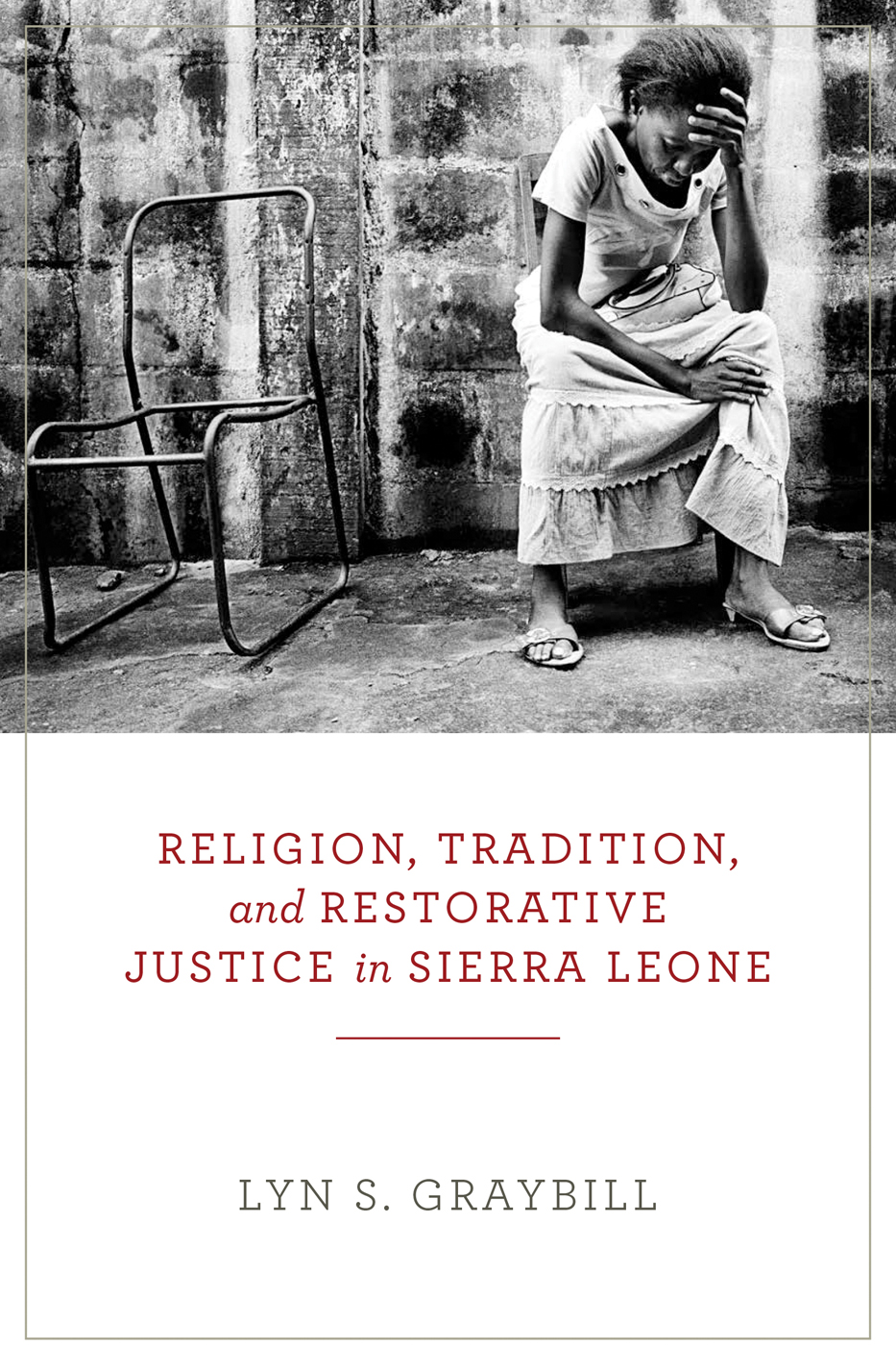

Religion, Tradition, and Restorative Justice in Sierra Leone

LYN S. GRAYBILL

Religion, Tradition, and Restorative Justice in Sierra Leone

UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME PRESS

NOTRE DAME, INDIANA

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

www.undpress.nd.edu

Copyright 2017 by the University of Notre Dame

All Rights Reserved

Published in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Graybill, Lyn S., author.

Title: Religion, tradition, and restorative justice in Sierra Leone / Lyn S. Graybill.

Description: Notre Dame : University of Notre Dame Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016058507 (print) | LCCN 2017005371 (ebook) | ISBN 9780268101893 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 0268101892 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780268101909 (pdf) | ISBN 9780268101916 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Sierra LeoneReligionHistory20th century. | Religion and politicsSierra Leone. | Sierra Leone. Truth and Reconciliation Commission. | Transitional justiceSierra Leone. | Reparations for historical injusticesSierra Leone. | Restorative justiceSierra Leone. | ReconciliationPolitical aspectsSierra Leone.

Classification: LCC BL2470.S55 G73 2017 (print) | LCC BL2470.S55 (ebook) | DDC 201/.7209664dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016058507

ISBN 9780268101916

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at .

Dedicated to the Honors Political Science Class of 2010 at Fourah Bay College: Mohammed Dukulay, Lindsay Ellis, Dennis George, Yayah Jalloh, Albert Jusu, Christocia Ebu Kawaley, Sahr Kendema, Manjia Success Kobba, Joseph Mallah, Osman Kabiru Mansary, Sidiru Deen Tejan Moiguah, and Edward Bai Turay.

CONTENTS

I wish to express gratitude for friends and colleagues who read earlier versions of the manuscript, especially Daniel Philpott, Scott Appleby, and John Paul Lederach at the University of Notre Dame. I appreciate the valuable comments of the anonymous reviewers and also those of David Keen, whose critiques I incorporated in this final version. I am especially indebted to Stephen Wrinn, Stephen Little, and Robyn Karkiewicz for shepherding the project to publication.

The book could not have been completed without the generous funding of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), whose grant afforded me the opportunity to travel to Sierra Leone in the summer of 2007 to conduct interviews. The Fulbright Scholarship Program also supported my work in Sierra Leone in 200910. Dana van Brandt, the public affairs officer at the US Embassy in Freetown, and Amy Challe, the Fulbright coordinator, were most helpful in facilitating my research. I also am grateful for the friendship of the other Fulbrighters: Jimmy Kandeh, Zoe Marks, and Niloufar Khonsari.

Two people in particular in Sierra Leone deserve mention. I learned much from the Reverend Moses Khanu, former director of the Inter-Religious Council (IRC), and at the time a member of the Sierra Leone Human Rights Commission. He opened up the archives of the IRC to me and graciously provided me his own written account of the role of the IRC during the war and postwar period. I also am indebted to John Caulker, executive director of Fambul Tok International. I met with him several times between 2006 and 2010 to learn more about the traditional methods of reconciliation his organization fosters. I appreciate all the people who were kind enough to be interviewed; their names are included in the appendix and bibliography.

I would be remiss in not mentioning Abdul Bah, driver extraordinaire, friend, and confidant. Thanks also to my husband, Jamie Aliperti, who read every word of the book multiple times and whose skillful editing improved the prose immensely. I dedicate this book to the students in my Honors Political Science class at Fourah Bay College, whose encouragement and support were unwavering.

When my book, subtitled with the unanswered question Miracle or Model?, on the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (SATRC) was published in 2002, Sierra Leone had just begun its path to truth and reconciliation, largely on the basis of the South African model, suggesting that the South African case had not been a onetime occurrence but would likely be replicated elsewhere on the continent.1 The criticisms against the Sierra Leonean TRC, while not unlike those made against its South African predecessor, were moderated by the existence of the Special Court, operating at the same time, and thus met the objections of those who worried that human rights violations would take place with impunity unless there was also punishment. In short, and to simplify many different arguments, critics of the SATRC found its emphasis on reconciliation rather than on justice undesirable.

In particular, secular critics were suspicious of the use of religion and tradition in proceedings they believed should be governed by reason, law, and objectivity. One letter to the Mail and Guardian newspaper expressed the common complaint: I understand how Desmond Tutu identifies reconciliation with forgiveness. I dont, because Im not a Christian and I think its grossly immoral to forgive that which is unforgivable.2 A young woman opined, What really makes me angry about the TRC and Tutu is that they are putting pressure on me to forgive. I dont know if I will ever be able to forgive. I carry this ball of anger within me and I dont know where to begin dealing with it. The oppression was bad, but what is much worse, what makes me even angrier, is that they are trying to dictate my forgiveness.3 Anthropologist Richard Wilson complained that, Commissioners never missed an opportunity to praise witnesses who did not express any desire for revenge. The hearings were structured in such a way that any expression of a desire for revenge would seem out of place. Virtues of forgiveness and reconciliation were so loudly and roundly applauded that emotions of revenge, hatred and bitterness were rendered unacceptable, an ugly intrusion on a peaceful, healing process.4

Were these critics onto something? Did people harbor negative views about the process their leaders had chosen for them to deal with the past? Or was this religious-redemptive model broadly accepted by South Africans, who are also overwhelmingly Christians?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the South African TRCs chairman, believes that reconciliation is not just biblically based but is also central to African tradition embodied in the notion of ubuntu. In African traditional thought, the emphasis is on restoring evildoers to the community rather than on punishing them. Tutus own description of ubuntu is enlightening: Ubuntu says I am human only because you are human. If I undermine your humanity, I dehumanize myself. You must do what you can to maintain this great harmony, which is perpetually undermined by resentment, anger, desire for vengeance.5Ubuntu, then, emphasizes the priority of restorative as opposed to retributive justice. Critics like Wilson who challenge this view argue that to view African tradition and law as completely excluding revenge is wishful romantic naivet.6

This debate fascinated me. To what degree were South Africans in particular, and Africans in general, more supportive of restorative approaches? Or was this approach pushed on people by religious personalities like Archbishop Tutu, when it did not actually resonate with their beliefs, understandings, and perspectives? While opinions about the success of the South African TRC are divided, and many people wish it had done more in the way of making reparations to victims, the basic supposition that acknowledging wrongdoing can promote reconciliation is not generally challenged (although most South Africans criticize how few perpetrators ultimately confessed their deeds).

Next page