Kinshasha Holman Conwill - Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies

Here you can read online Kinshasha Holman Conwill - Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Amistad, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies

- Author:

- Publisher:Amistad

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

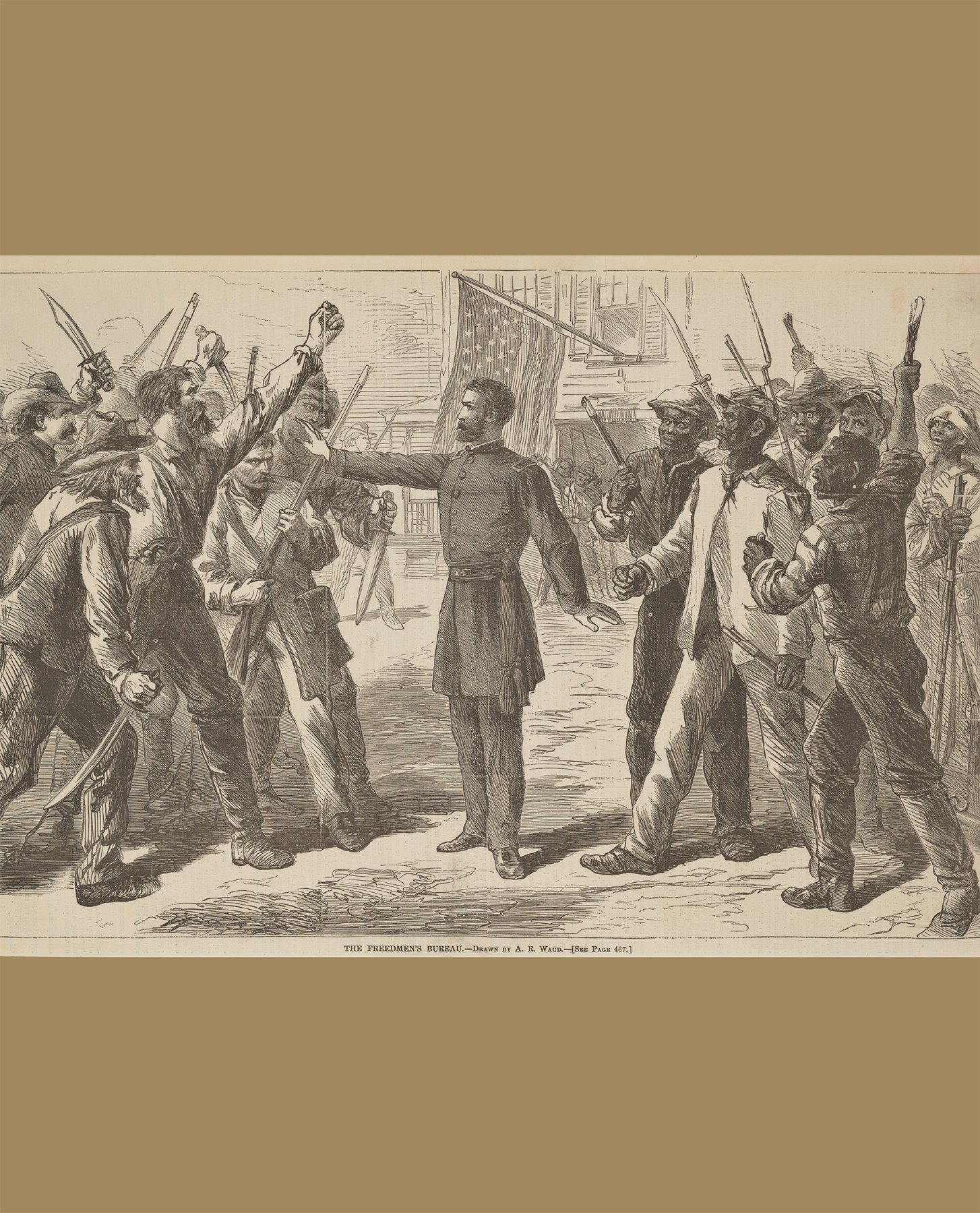

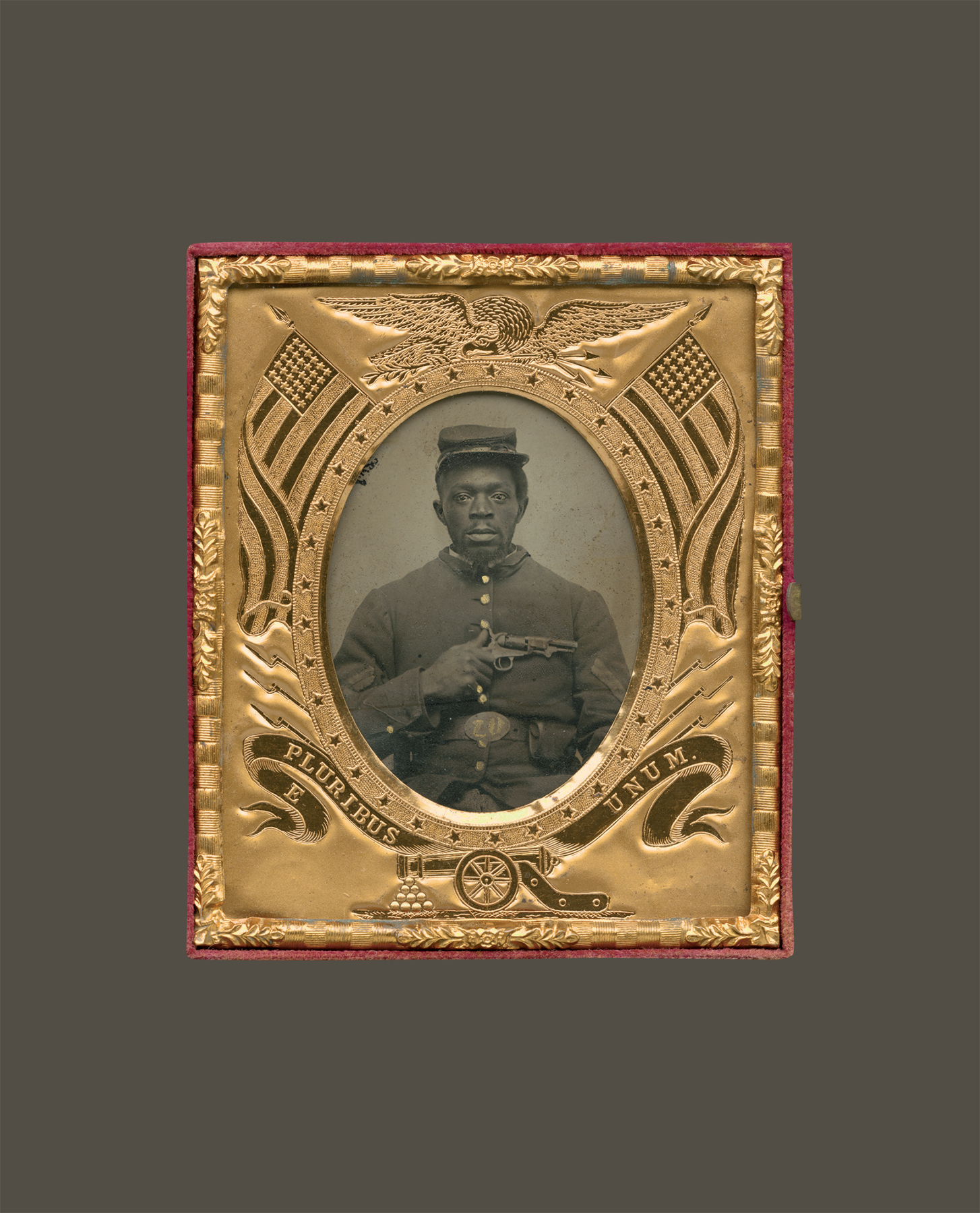

The companion volume to the Smithsonians National Museum of African American History and Culture exhibit, opening in September 2021

With a Foreword by Pulitzer Prize-winning author and historian Eric Foner and a preface by veteran museum director and historian Spencer Crew

An incisive and illuminating analysis of the enduring legacy of the post-Civil War period known as Reconstructiona comprehensive story of Black Americans struggle for human rights and dignity and the failure of the nation to fulfill its promises of freedom, citizenship, and justice.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, millions of free and newly freed African Americans were determined to define themselves as equal citizens in a country without slaveryto own land, build secure families, and educate themselves and their children. Seeking to secure safety and justice, they successfully campaigned for civil and political rights, including the right to vote. Across an expanding America, Black politicians were elected to all levels of government, from city halls to state capitals to Washington, DC.

But those gains were short-lived. By the mid-1870s, the federal government stopped enforcing civil rights laws, allowing white supremacists to use suppression and violence to regain power in the Southern states. Black men, women, and children suffered racial terror, segregation, and discrimination that confined them to second-class citizenship, a system known as Jim Crow that endured for decades.

More than a century has passed since the revolutionary political, social, and economic movement known as Reconstruction, yet its profound consequences reverberate in our lives today. Make Good the Promises explores five distinct yet intertwined legacies of ReconstructionLiberation, Violence, Repair, Place, and Beliefto reveal their lasting impact on modern society. It is the story of Frederick Douglass, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Hiram Revels, Ida B. Wells, and scores of other Black men and women who reshaped a nationand of the persistence of white supremacy and the perpetuation of the injustices of slavery continued by other means and codified in state and federal laws.

With contributions by leading scholars, and illustrated with 80 images from the exhibition, Make Good the Promises shows how Black Lives Matter, #SayHerName, antiracism, and other current movements for repair find inspiration from the lessons of Reconstruction. It touches on questions critical then and now: What is the meaning of freedom and equality? What does it mean to be an American? Powerful and eye-opening, it is a reminder that history is far from past; it lives within each of us and shapes our world and who we are.

Kinshasha Holman Conwill: author's other books

Who wrote Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.