The author would like to expresses his gratitude to Oleg Alexandrovich Smirnov, CEO of the SNS Group of Companies for sponsoring publication of this book.

P eoples attitudes to tobacco cover a whole gamut of emotions, from I cant live without a cigarette to I regard tobacco as one of the vilest enemies

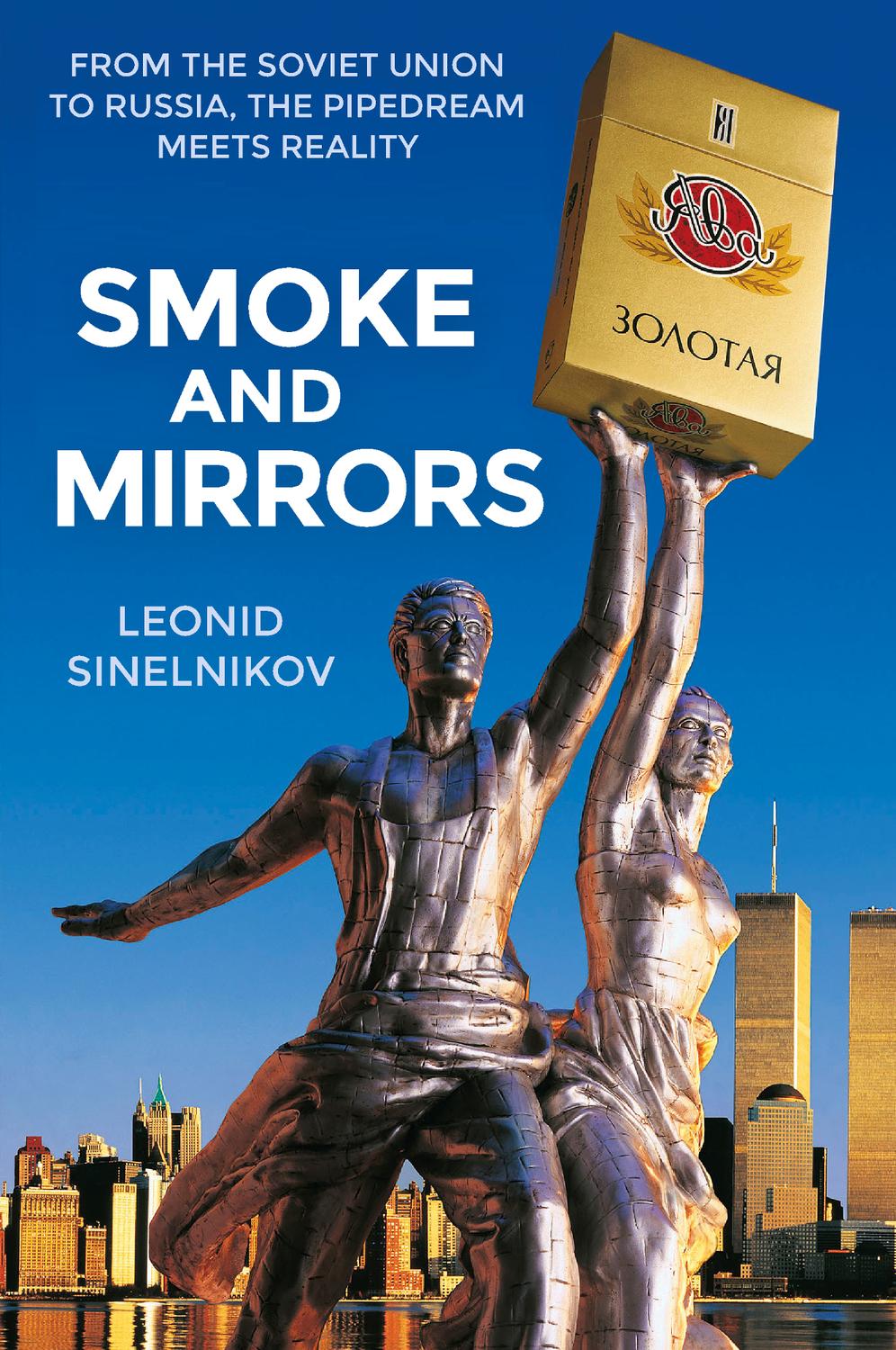

If you ask me about tobacco, you will risk getting the answer, Read my book! because in my case, tobacco has been my lifes career. There is probably no point now in dwelling on whether or not I chose the right path. In any case, back when, as a freshly baked Moscow college graduate, I was sent to work at the tobacco factory, I had little choice in the matter. Ill do a stint at the Yava factory, I told my parents, not imagining that this stint would go on for half a century.

I never thought that I would witness such changes in attitudes to smoking as we are seeing now the world over. Even in Russia, where people are fairly conservative in their habits, cigarette consumption is in decline. In the USSR, cigarettes were considered a vitally important product without which consumers simply could not live a view borne out by the serious unrest that broke out whenever there were tobacco shortages. This is why the countrys leadership paid great attention to ensuring that the country was properly supplied with tobacco products, putting tobacco on a par with bread and vodka. In the rest of the world too, of course, smoking was a major influence in society and something that governments kept a watch over, but the problems there were of a different nature from those in Russia.

Now, smokers are giving up or cutting down on cigarettes of their own accord. They are switching to electronic cigarettes or other products that mimic traditional smoking but without the burning of tobacco. I will touch upon this topic in the concluding part of the book. However, my main subject is much broader than the traditional production of cigarettes. In this book, dear reader, tobacco is also a pretext to describe the people I have known and the events that I have been involved in and witnessed, to talk about the difficult times our country has faced and about the fates of people who made their contribution to Russias development.

Was the tobacco industry in the USSR just an anomalous weak point in a viable system, or were we all, by constantly plugging the holes in a shortage-based economy, propping up an illusion of the sustainability of the command system? To use an English expression, was it all just smoke and mirrors? That is for you to judge. The purpose of my account is to help the next generation draw the right conclusions from the lessons of history.

I began pondering over the fundamental problems of the system when it became clear that our country had hit a dead end. The sequence of deaths of one elderly General Secretary after another provided us with a fecund source of bleak jokes, but precious little in terms of hopes for the future. And when a new leader, Gorbachev, appeared atop the political Olympus, no one expected his appointment to turn the life of this vast country upside down. That era, which became popularly known throughout the world as perestroika, may without any exaggeration be called the brightest period in the history of the USSR. Events that brought long-established stereotypes crashing down and had life-changing consequences for the whole country occurred in rapid succession. The man who instigated and inspired these momentous changes was the General Secretary himself, Mikhail Gorbachev, who very astutely identified the primary targets of long-overdue reforms.

Almost immediately after he came to power, concepts that were fundamentally new to Soviet power were suddenly proclaimed as policy. Perestroika and glasnost were designed to overcome the worst vices of the Brezhnev era: stagnation and the concealment of the real state of affairs in the country from the people. There was particular awe over the way Mikhail Sergeyevich interacted with members of the public. People sat in astonishment at television reports covering Gorbachevs visits to various places around the country. It was in the course of Mikhail Sergeyevichs frank and open engagement with the public that the catchphrase we cannot live like this was born.

I think that those of my compatriots who these days like to criticise Gorbachev, accusing him of all the mortal sins, would do well to remember how we lived before he bravely took on the challenge and responsibility of breaking a monstrously vicious circle.

I shall begin with what I remember well, with an account of my earliest impressions of the country in which I was born and raised. I was thirteen when Stalin died. Did I understand then, as a studious secondary school pupil, that the death of the tyrant would offer a way out of the brutal totalitarianism under which we had been living? Of course not. It had never entered my head that the poverty in which we lived resulted from the way we were governed. Indeed, it was only later that I realised how badly we had been living. But at the time? Poverty was the norm, and thoughts about material well-being did not even arise. We had been taught that we had to work in the interests of the state, to help rebuild the country after the devastation of the war. As for material comforts that was all bourgeois prejudice.

My family lived in a two-storey building next to Rizhsky (then Rzhevsky) railway station. The rooms led off a communal corridor. There were eight families living along our corridor. Heating came from coal-fired stoves. No one had a kitchen. The women of each household would cook on a kerosene stove on a little table positioned next to the door of her apartment. The toilet and washbasin were located at the end of the corridor next to the cold stairwell. There was no question of a shower. Each morning, when everyone was in a rush to get to work, a queue would form to the so-called communal facilities.

It amazes me to this day to think how my parents managed to get through those unthinkable times. They would go to work early in the morning and come home at around eight in the evening. While mama began to cook, my father would put on a bodywarmer, fetch firewood and coal from the shed and set about heating the stove. The air was damp, and the warmth did not linger long. By the time I got home from school, it was cold in our room. My most fervent wish was that it could be warm and cosy.

The working week lasted six days. On the only day off Sunday my father and I would go to the market to buy food, and then the whole family would go to the bathhouse. Getting into the bathhouse meant standing in a queue for several hours. And so life would go on, week after week. This was how the majority of Muscovites lived. It was no better for those who lived in packed communal flats (kommunalki) were reserved for important officials. But even then, there was a price to pay, since people in that category were at an especially high risk of falling victim to repressive measures. These living arrangements were in keeping with the Stalinist ideology of extending the principles of collectivism even to citizens personal lives, so that people spent as little time as possible on their own or in the family circle and had minimal opportunity for heart-to-heart conversation.