The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Maybe you arent 100 percent sure what the secretary of defense does all day. Or youre feeling a bit iffy as to what free speech actually means. Perhaps youve been pretending you know the definition of federalism.

What luck, then, that youve found yourself in possession of the basics of this democratic republic all in one place. This is your users guide to American democracy, giving you the fundamentals on everything from the presidency to our election system to our basic civil rights. We parse the great hulking mass of our government into essential knowledge.

In order to enjoy and preserve this democracy, we have to know how it works. Understanding your rights as an American citizen can protect your job, your health, and your freedom. An awareness of the way things work around here is valuable armor. But its a lot to remember, so we wrote it down in a book for you.

We do this for a living as the hosts of a public radio show and podcast, Civics 101. We guide people through the maze of American democracyfrom the Bill of Rights to executive privilege to Congressional investigations. Our show is a primer that leaves listeners better prepared to be engaged, aware citizens. Civics 101 was started in 2016 as a response to a flood of questions coming into the station, including, Can he/she/they really do that? What does the secretary of state do all day? What is the Defense Department? and How is the House different from the Senate? It was a wonderful opportunity for us to admit we barely knew the answers ourselves, and to call up the experts who do. Weve relied on the information weve gleaned from them to write this primer. The information in these pages was gathered from our countrys most primary sources, the foundational documents, and what we found to be the most helpful of the nearly 250 years of scholarship and debate that have swirled around this democratic experiment since it first launched.

Within this book youll find what we have learned over years of wait, what? and so thats how it works, and can you explain that to us one more time? Weve played democracys interpreter so you dont have to. As far as your family is concerned, youve always understood the finer points of McCulloch v. Maryland.

YOU CANT HAVE IT ALL

If theres one thing you have to know about the power structure of our federal government, it is that it, like Gaul, like Lears kingdom, is divided into three. Our U.S. Constitution is the longest-surviving government document, and the first thing it does (after it says hello) is lay out who does what. This system is dependent upon the separation of powers and checks and balances. And these are not the same thing.

Separation of Powers: This just means that our government is divided into three branches, and no branch has the same powers as any other; they are completely independent and complementary.

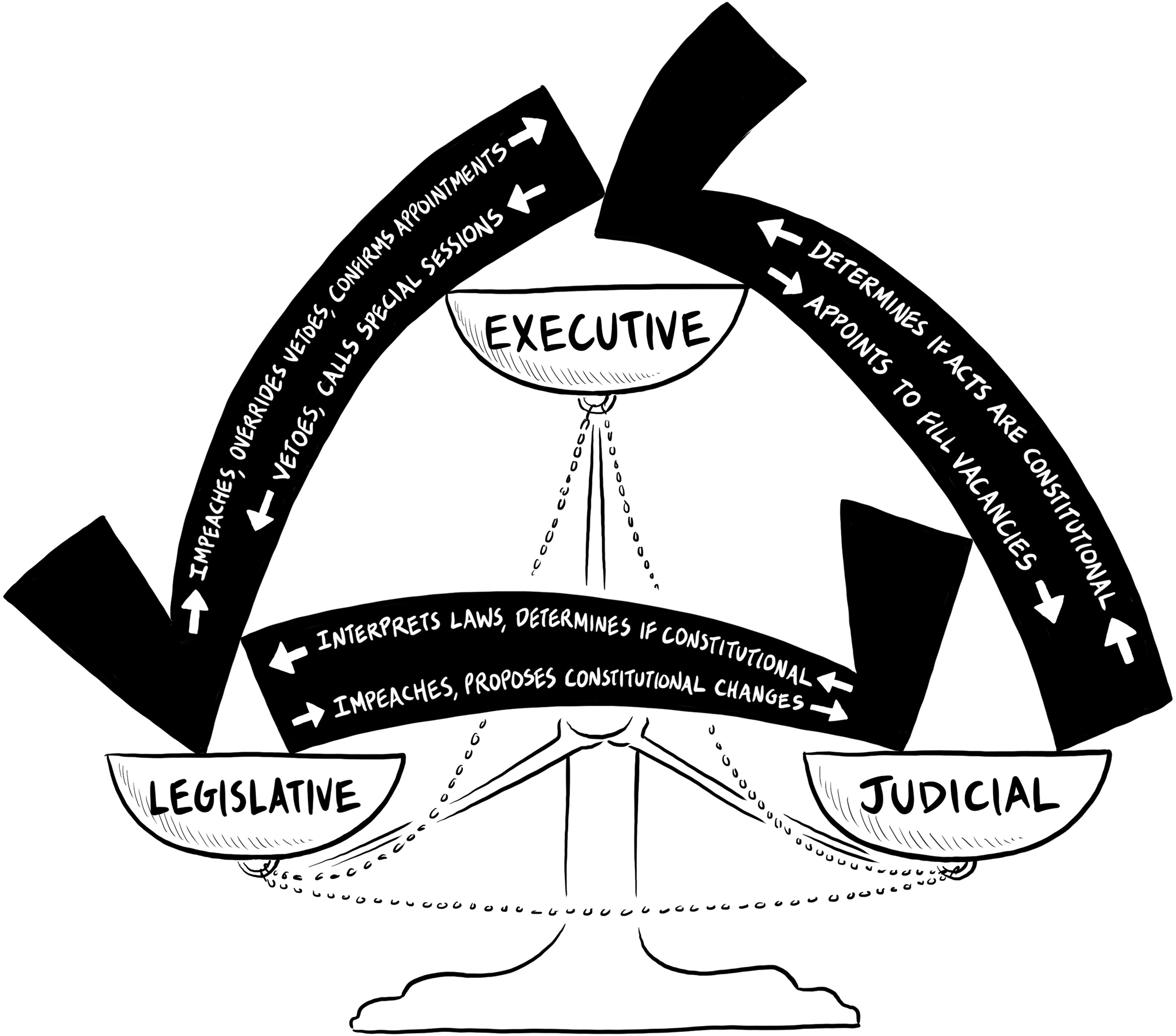

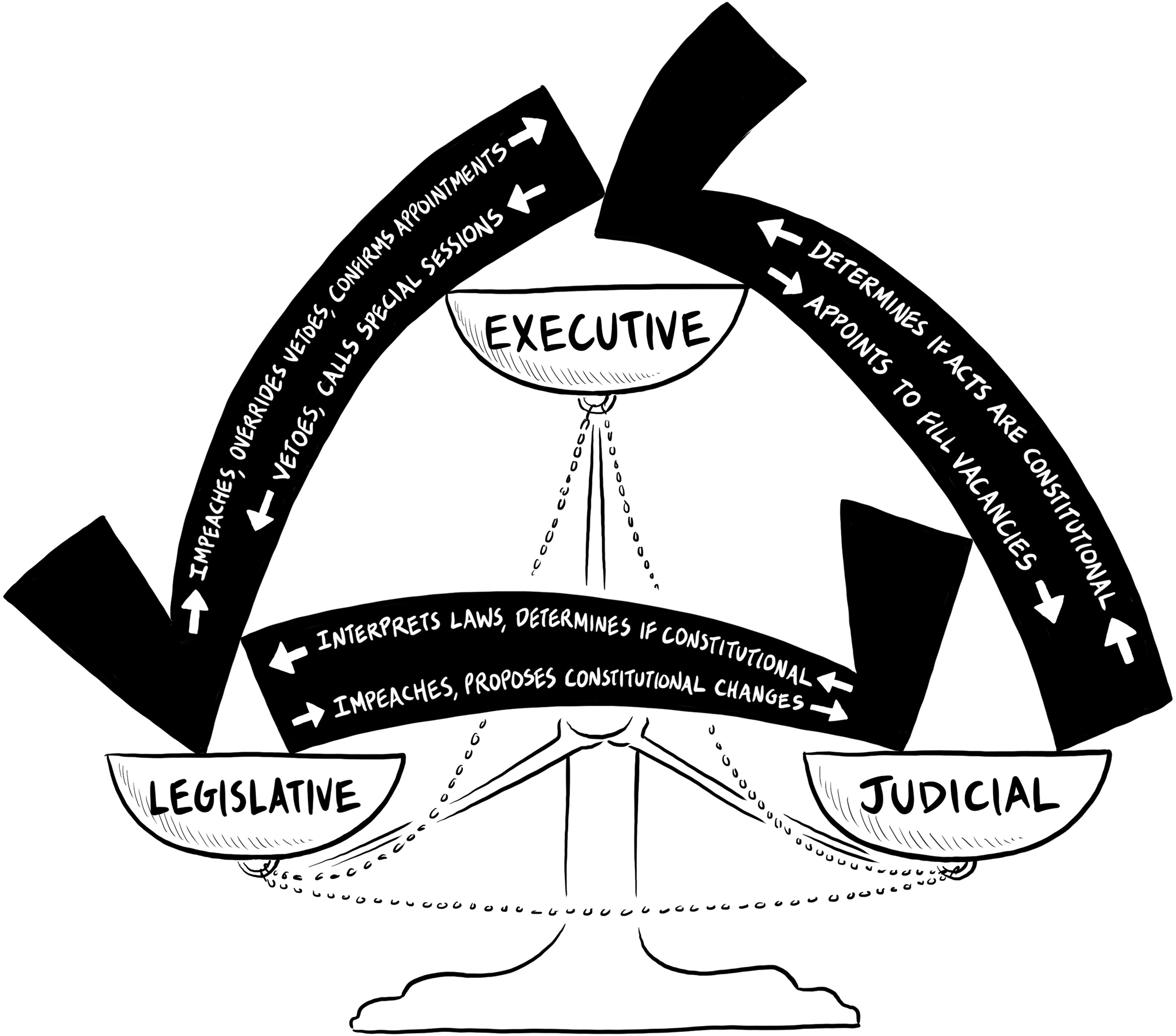

Separation of Powers: This just means that our government is divided into three branches, and no branch has the same powers as any other; they are completely independent and complementary. Checks and Balances: This means that no branch of the government can be too powerful, as every major power can be checked, or blocked, by another branch. In James Madisons essay Federalist 51, he said that in this system ambition must be made to counteract ambition. He knew that politicians would be passionate about their ideals and would do anything to advancethem. These checks prevent one branch from unilaterally setting policy. Heres a diagram of how the branches keep one another in line.

Checks and Balances: This means that no branch of the government can be too powerful, as every major power can be checked, or blocked, by another branch. In James Madisons essay Federalist 51, he said that in this system ambition must be made to counteract ambition. He knew that politicians would be passionate about their ideals and would do anything to advancethem. These checks prevent one branch from unilaterally setting policy. Heres a diagram of how the branches keep one another in line.

At the outset, it seems like the House of Representatives and the Senate do pretty much the same thing.

Senators and representatives drive, walk, or take the secret tiny electric underground train to their respective chambers. There, they propose legislation, talk about it, and vote on it. But while they share many powers, these two houses are not both alike in dignity. Or perceived clout, at least. The length of terms, number of members, unique powers, and methods of legislation make the House and Senate as different as chalk and cheese. But before we do a side-by-side comparison, lets get some terminology out of the way.

WHAT WE TALK ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT CONGRESS

When we speak of Congress, were talking about both the House of Representatives and the Senate. They are that mighty first branch, the legislative, whose powers are established in Article I of the Constitution.

CONSTITUTION 101: Our constitution consists of seven articles written on four parchment pages. Article I, which establishes the legislative branch, gets far and away the most ink of them all, coming in at just over two pages by itself. And words are power! The more you have, the more things you can do. The founders clearly intended that Congress, not the president, was to be the most powerful arm of our government. That said, they also didnt want a complete legislative dictatorship, so they carefully explained what Congress could and could not do.

While they are both technically houses, when we say the House we mean the House of Representatives. Those in the House are addressed as congresswoman/-man/-person. And while senators do work in Congress, theyre addressed as senator.

WHY TWO HOUSES?

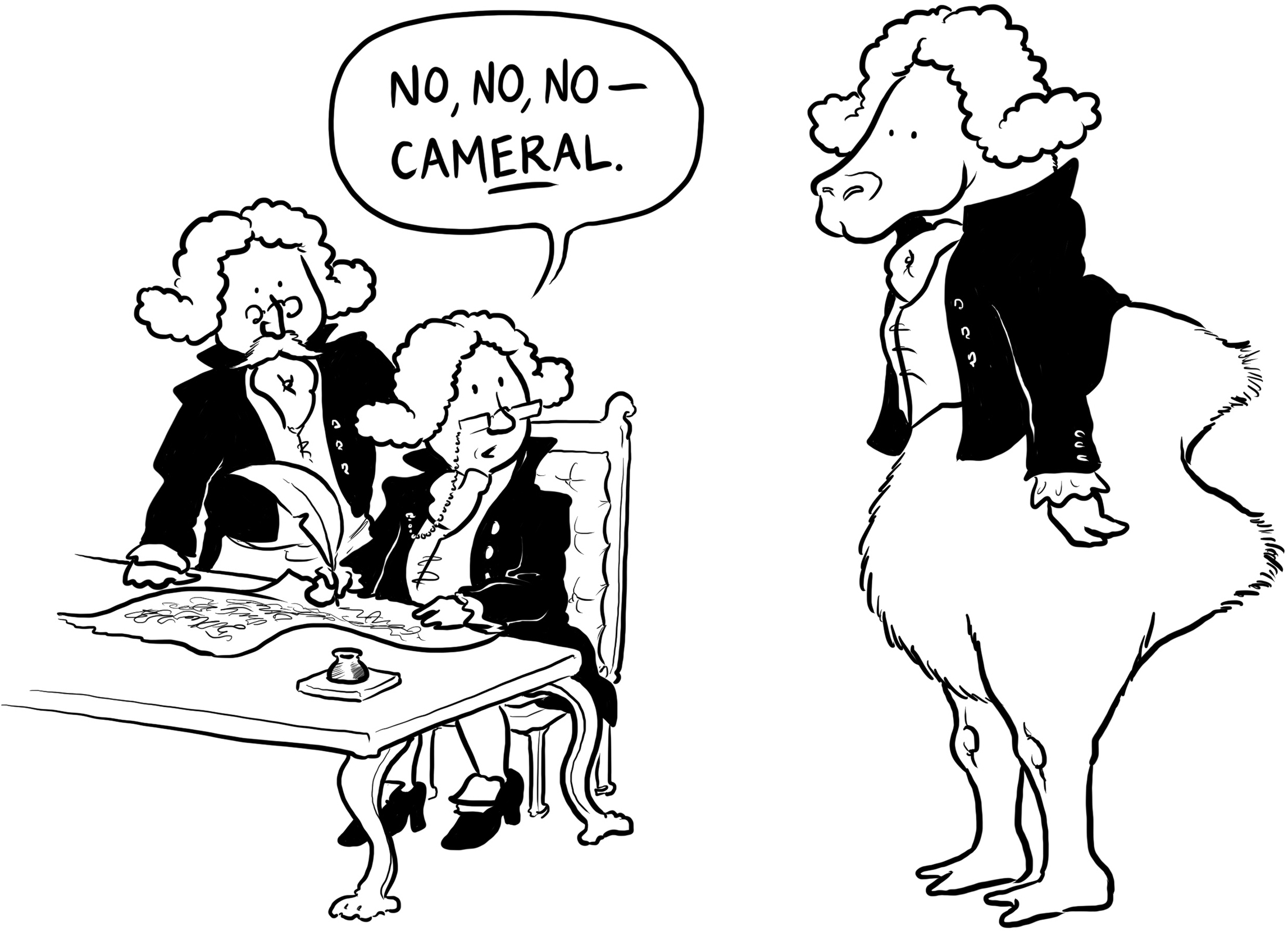

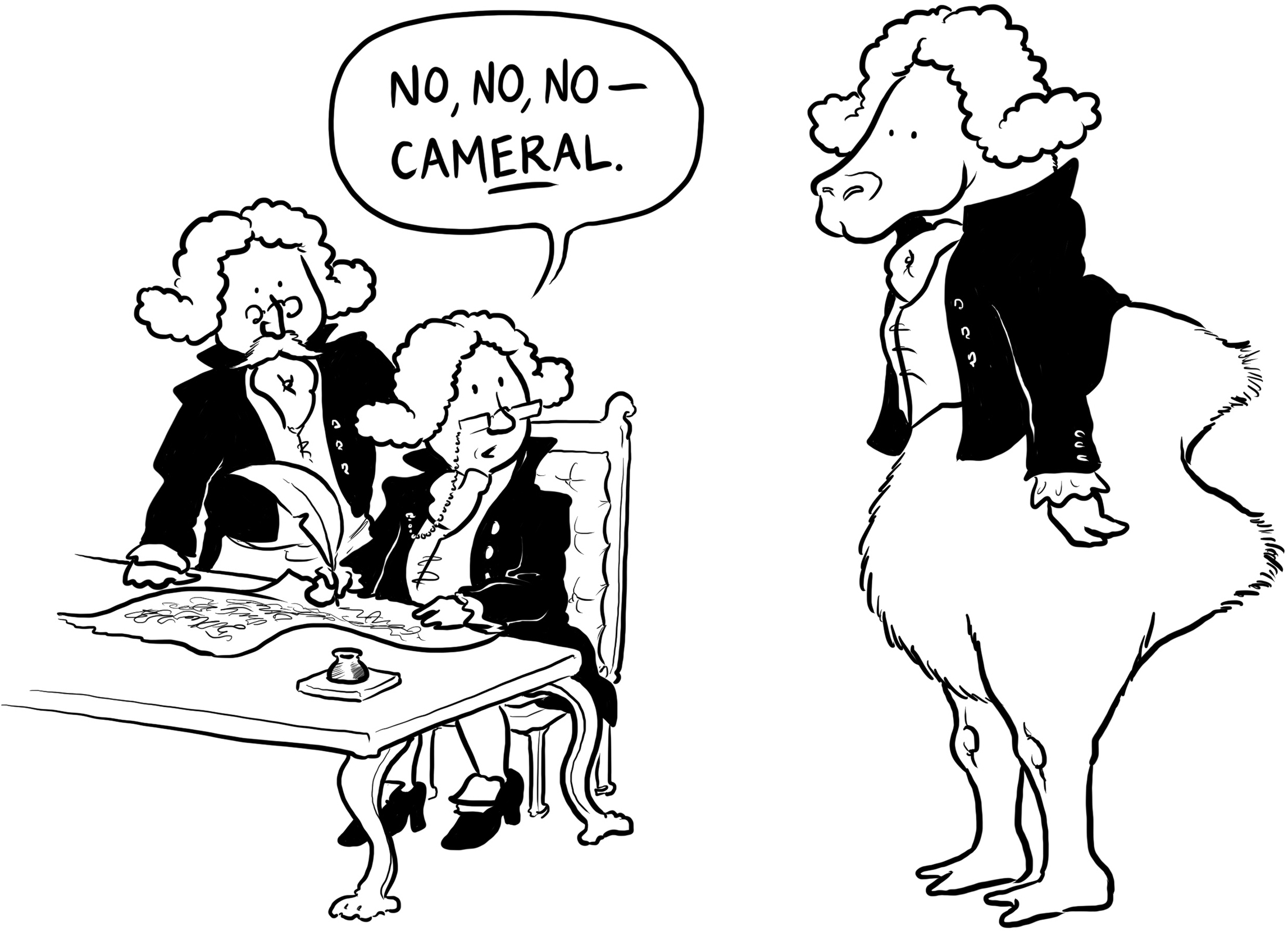

Why not just have one house and be done with it? Why not a nice, pat, unicameral legislature that passes bills for the president to sign? Well, that was how we did things under the Articles of Confederation, our much maligned first constitution. And to be fair, there are some successful one-house legislatures out there (lookin at you, Nebraska!), but the bicameral system was born as a solution to one of the fiercest debates at the Constitutional Convention

THE GREAT COMPROMISE

When the fifty-five delegates from twelve colonies (Rhode Island was a no-show) were hammering out our new system of government in 1787, there arose a seemingly insurmountable issue of representation. How many people from each state should be elected to Congress? Before the convention even started, James Madison had drafted the Virginia Plan (also called the Randolph Plan or the amusingly blunt Big State Plan), which said that representation in Congress should be based on the number of free inhabitants. Enslaved Americans would initially not be counted toward apportionment. A big whanging state like New York would therefore have many times the power of a state like Delaware. The smaller states were more likely to back William Patersons New Jersey Plan (only referred to as the Little State Plan when New Jersey wasnt in the room), which gave each state one vote, regardless of its size. And thus we got to the Great Compromise, where one house, the House of Representatives, was proportionate to the population of free inhabitants in each state, with enslaved people counting as three-fifths of a person (Native Americans not counting at all), and the other chamber, the Senate, consisting of two people from each state.

Separation of Powers: This just means that our government is divided into three branches, and no branch has the same powers as any other; they are completely independent and complementary.

Separation of Powers: This just means that our government is divided into three branches, and no branch has the same powers as any other; they are completely independent and complementary.