Contents

Guide

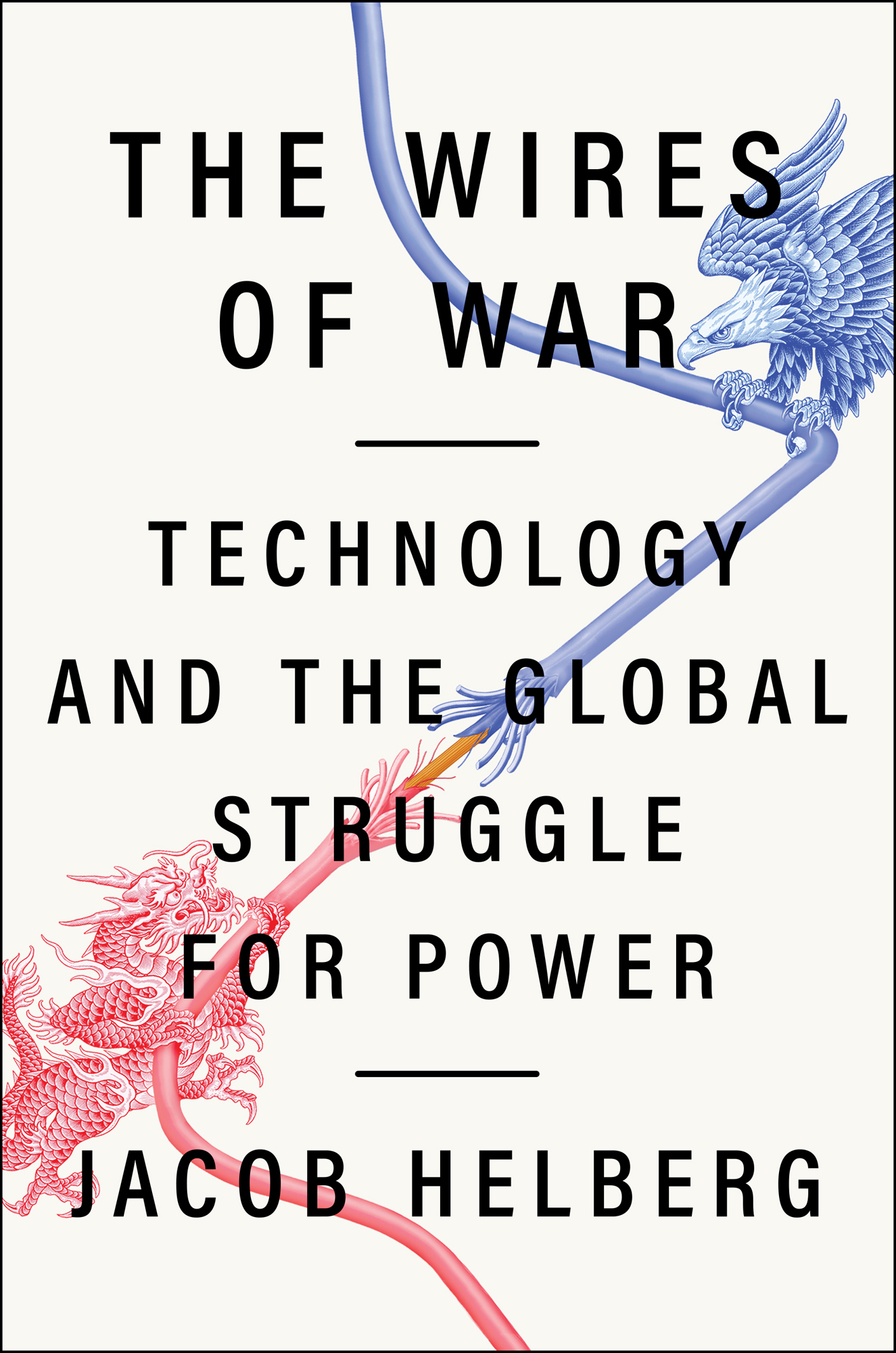

The Wires of War

Technology and the Global Struggle for Power

Jacob Helberg

AVID READER PRESS

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Jacob Helberg

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Avid Reader Press Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Avid Reader Press hardcover edition October 2021

AVID READER PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Joy OMeara @ Creative Joy Designs

Jacket design by Rodrigo Corral Design

Author photograph Christian Oth

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-9821-4443-2

ISBN 978-1-9821-4445-6 (ebook)

This book is dedicated to my husband, Keith Rabois, and our two kids, Eli and Anne Helberg Rabois.

Prologue

I remember just about every detail of the day that turned my world upside down.

It was a fall morning in San Francisco in 2017, as ordinary as any other. In the cafeteria of Googles Spear Street building, I helped myself to my usual scrambled eggs, then traced the trolley tracks on my walk to the policy office in a separate Google building in the bustling Embarcadero district. Googlers of all ages were scattered throughout our office space, typing furiously, attending meetings, or taking calls in soundproof telephone booths. As Googles lead for news policy, it was my job to help the company think through the implications of much of the work my colleagues around me were engaged in.

I settled into a desk on the third floor and opened my laptop to answer email. I was typing away when I learned that we had a problempotentially a big one. Unfortunately, I cant recount many of the sensitive internal details. But the issue had to do with the epidemic of so-called fake news during the 2016 election. Although the press had reported on incidents of disinformation spreading online during the election, for much of 2017 most technologists in Silicon Valley still believed that assuming technology platforms influenced the electoral outcome in any material way would be a leap too far. It can be hard to remember, through the smokescreen of hindsight and all that weve learned since, that this was the prevailing consensus at the timebut it was.

To fully understand what happened, you first have to appreciate how Google works day to day. Beyond Googles search function, the company offers a host of products that require accounts. Anyone can watch videos on YouTube, one of Googles subsidiaries. But to post a video or to place an ad on Google, you need to create an account. Google regularly eliminates accounts that spew spam or serially infringe on established copyrights.

What Google had discoveredas the media later reportedwas that an organization called the Internet Research Agency had purchased thousands of dollars of ads on Google.

Even in my jeans and long-sleeve crew neck, the office suddenly felt chilly. Across from our building was Rincon Park, with its sixty-foot-tall sculpture of a bow and arrow partially sunk into the grass, meant to evoke Cupids arrow finding its mark in free-loving San Francisco. Right now, the symbolism felt a little too close to home. In our rambunctious democratic system and freewheeling social media platforms, the Russians had hit the bulls-eye.

Across Silicon Valley, revelations such as these had set off alarm bellsand raised serious questions. Were social media platforms more vulnerable to foreign attacks than wed realized? How seriously had we been hackedif at all? Were other countries using our platform to quietly pursue nefarious goals?

Its not that we hadnt contemplated the challenge of cybersecuritywe did. Google had extensive cybersecurity systems in place and even set up an in-house counterespionage team precisely to protect our platforms from sophisticated malign actors. Google also had preexisting policies addressing adjacent aspects of the foreign interference challenge. Nevertheless, no one could have anticipated having to deter and defend against state-sponsored attacks on democratic political systems carried out through highly sophisticated subversions of everyday commercial products. That, most of us in tech assumed, was the governments jobthe responsibility of the Pentagon and the National Security Agency (NSA). But sitting there at Google, shocked and confused, it felt as if Washington had failed to protect us. Now Silicon Valley would have to figure out how to respond.

Throughout the 2016 presidential campaign, Americans were vaguely aware that something was awry. Faceless Twitter accounts with grammar out of a Boris and Natasha cartoon spewed absurd untruths, claiming that Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton was desperately sick But 2016 pointed to something new. Donald Trumps electoral upset marked a turning point, the moment when Americans saw clearly how a foreign country could use digital technology to manipulate the information flowing into the body politic in a way that would have been impossible a generation ago. It was, by some measure, the first time autocrats had turned our everyday Internet against us as a political weapon of war. But it wouldnt be the last.

Im a technologist. Like most of my peers in Silicon Valley, I came to Northern California because I believed in the tech industrys broader mission to help people around the world live more fulfilling lives. But over the three-plus years that I worked at Google, my day-to-day experience gradually became defined less by dreamy optimism and more by something darker. I found myself drafted into service on a pivotal battlefield of a rapidly expanding clash between democracy and autocracya conflict between fundamentally incompatible systems of global governance, simmering just below the threshold of conventional war.

For much of the past decade or so, this conflict remained largely unspokenand, in too many quarters, unrecognized. Gradually, however, the designs of the leading forces of authoritarianismRussia and Chinabecame harder to ignore. Then, in early 2020, the lethal coronavirus sprang into being in Wuhan, China, and began its deadly march across the globe. In a matter of months, the faade fell away. As Chinas leaders dissembled and its wolf-warrior diplomats bullied foreign nations, as former President Trump raged against China and engaged in a heated trade war, the contours of this new struggle came into focus. Suddenly, you could hardly pick up a newspaper without reading about this growing conflict.

The United States and China are actually in the era of a new Cold War, Shi Yinhong, an international relations professor and advisor to Chinas State Council, told the South China Morning Post.

In many ways, this new cold war is unlike the earlier struggle between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. As historian Hal Brands and Jake Sullivan, now President Bidens National Security Advisor, have argued, the Soviet Union was never a serious rival for global economic leadership; it never had the ability, or the sophistication, to shape global norms and institutions in the way that Beijing may be able to do.there is the continued threat of Moscows machinations, different from the days of the Soviet Union, but still immensely disruptive.