Who will invent Americas next great century?

The big ideas that will revolutionize the way we live will not emerge from our nations capital. They will be dreamt up, as they always have been, by enterprising Americans who hope to create positive value for others.

Encounter Intelligence is dedicated to promoting advances in innovation, education, and technology that will improve the lives of all Americans and unlock real opportunity for those who need it most.

Economists agree: The single biggest threat to future job growth in the United States is the surge of artificial intelligence. Gallup, January 2018

America is finally approaching full employment. But a chorus of experts claims that this happy situation will be short-lived. Their warning is not the usual one about unemployment rising again when the next recession hits. Instead, the proposition is more ominous: that technology is finally able to replace people in most jobs.

The idea that we face a future without work for a widening swath of the citizenry is animated by the astonishing power of algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI) and automation, especially in the form of robots. At last count, more than a dozen expert studies, each sparking a flurry of media attention, have offered essentially the same conclusion: that the amazing power of emerging technologies today really is different from anything weve seen before; that is, the coming advances in labor productivity will be so effective as to eliminate most labor.

It has become fashionable in Silicon Valley to believe that, in the near future, those with jobs will comprise a minority of knowledge workers. This school of thought proposes carving off some of the wealth surplus generated by our digital overlords to support a Universal Basic Income for the inessential and unemployable, who can then engage in whatever pastime their heart desires, except working for a wage.

It is true that something unprecedented is happening. America is in the early days of a structural revolution in technology, one that will culminate in an entirely new kind of infrastructure, one that democratizes AI in all its forms. This essay focuses on the factual and deductive problems with the associated end-of-jobs claim. In it, we explore what recent history and the data reveal about the nature of AI and robots, and how those technologies might impact work in the 21st century.

But before mapping out the technological shift now underway and its future implications, lets look for context at previous revolutions in labor productivity.

Grand transitions in productivity are episodic and powerful

One of humanitys oldest pursuits is inventing machines that reduce the labor-hours needed to perform tasks. History offers hundreds of examples. Each invention seemed amazing in its era. To note a handful of examples, in modern times, we have seen the arrival of the automatic washing machine in the 1920s; the programmable logic controller (PLC), which enabled the first era of manufacturing automation in 1968; the word processor in 1976; and the first computer spreadsheet in 1979.

History demonstrates that, when it comes to major technological dislocations, most forecasts get both the what and the when wrong.

As with the typing pools, rows of accountants ciphering, rooms full of draftsmen with sharp pencils, or other common workplace sights from bygone eras, it is easy to predict which groups will lose jobs from gains in labor productivity. It is far harder, on the other hand, to predict the kinds of new jobs and how many will appear. Its easy to see how an economy expanding due to accelerated productivity leads to added wealth, which, in turn, leads to more demand for existing products and services, all of which entail labor. But it is more challenging to predict the specifics of how new technologies invariably lead to unanticipated businesses producing new kinds of products and services, all employing people in entirely novel ways.

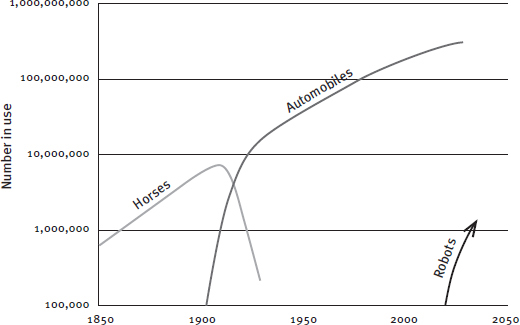

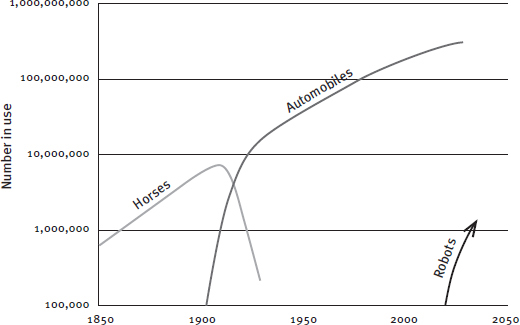

One of the most powerful advances in the history of labor productivity was the arrival in 1913 of a practical automobile. The very word automobile was coined to describe the automation of mobility, a long-time goal of humanity. The transition from grain-fed horses to petroleum-fueled automobiles took place with astonishing velocity precisely because the productivity benefits were so profound. (See .) Along the way, as every schoolchild learns, the automobile totally upended the character and locus of every kind of employment associated with centuries of transportation services. Gone forever were all the jobs and millions of acres of land devoted to the feeding, care and use of horses.

The 1956 invention of the shipping containeran idea patented by U.S. trucking-company owner Malcolm McLeanalso radically increased labor productivity. Containerization led to a 2,000% gain in shipping productivity in just five years and the end of centuries of rising employment for longshoremen (and, historically, they were all men). That gain in productivity rivaled that which took place in the previous century with the switch from sail to steam power: both radically lowered shipping costs, and both propelled world trade, prosperity and, derivatively, employment.

Figure 1. Grand Transitions in Labor Productivity, 18502050 (Projected)

Source: Adapted from Nakicenovic, Nebojsa

Containerization is also a clear example of how a new mode of business is made possible by building on a machine-based infrastructure invented and deployed by others: containerization could not have been effected prior to the availability of the precision powered cranes and gantries. That model matches exactly what Sears and Roebuck did in 1892, using the existing railroad infrastructure to launch their revolutionary retail empire, and what Amazon did a century later, using the existing Internet infrastructure to do the same.

One could wax lyrical about the pursuit of productivity. After all, the single most precious resource in the universe is the corporeal time we humans have. Maybe, someday, genetic engineers will find magic to change that. But it remains the case that every human being is born with a bank account with a maximum balance of about one million living hours. As with money, a million sounds like a lotuntil you start consuming it.

Technology is the only leverage weve ever had to buy time

Using technology to reduce or amplify human labor is more than metaphysical, though. Productivity is central to economic progress. As economic historian Joel Mokyr has pointed out, technological innovation gives society the closest thing there is to a free lunch. From the dawn of the industrial revolution, it has enabled the near-magical increase in the availability of everything, from food and fuel to every imaginable service. There is an enormous body of scholarship devoted to the study of how productivity increases both wealth and employment. Providing a coherent theory around that reality earned Robert Solow a 1987 Nobel Prize.

Epoch-changing shifts in technology do two inter-related things: they propel economies, and they introduce unintended disruptions across society. None of historys technological disruptions were predicted by economists or policymakers. But once a disruption is underway, pundits pile on fast with predictions about implications and impactspredictions that are almost always wrong, both in character and in outcomes.