Contents

Guide

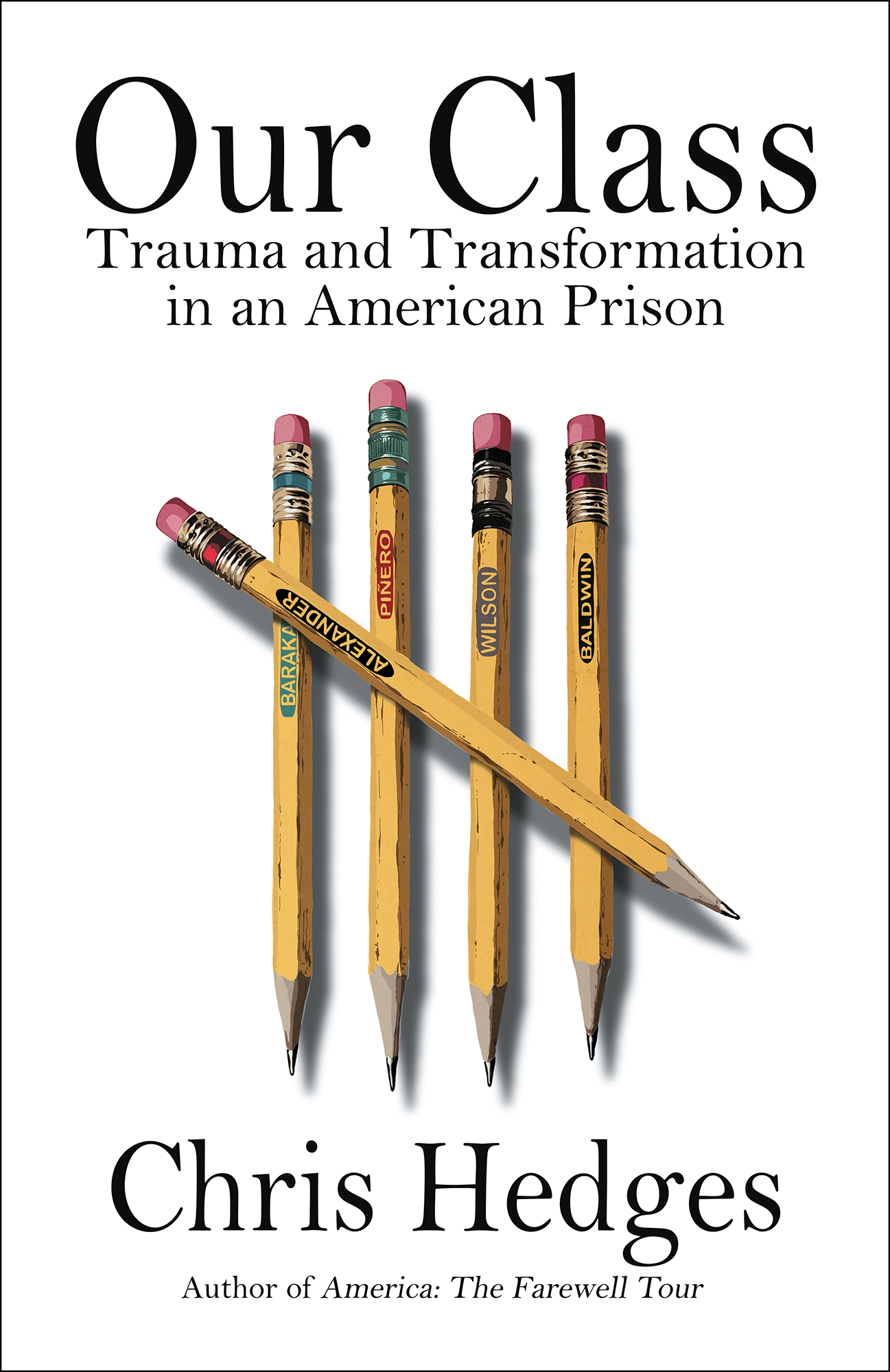

Our Class

Truma and Transformation in an American Prison

Chris Hedges

Author of America: The Farewell Tour

Also by Chris Hedges

America: The Farewell Tour

Unspeakable (with David Talbot)

Wages of Rebellion: The Moral Imperative of Revolt

War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning

Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt (with Joe Sacco)

The World as It Is: Dispatches on the Myth of Human Progress

Death of the Liberal Class

Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle

When Atheism Becomes Religion: Americas New Fundamentalists

Collateral Damage: Americas War Against Iraqi Civilians (with Laila Al-Arian)

American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America

Losing Moses on the Freeway: The 10 Commandments in America

What Every Person Should Know About War

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Summit Study, Inc.

Frontispiece photo courtesy of the author

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition October 2021

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Lewelin Polanco

Jacket design and artwork by Mr. Fish

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hedges, Chris, author.

Title: Our class : trauma and transformation in an American prison / Chris Hedges.

Description: First hardcover edition. | New York : Simon & Schuster, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021018661 | ISBN 9781982154431 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781982154448 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781982154455 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: East Jersey State Prison. | PrisonersNew JerseyRahwayCase studies. | PrisonersEducationNew JerseyRahwayCase studies. | CriminalsRehabilitationNew JerseyRahwayCase studies. | Criminal justice, Administration ofNew JerseyRahwayCase studies.

Classification: LCC HV9475.N52 E244 2021 | DDC 365/.60922749dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021018661

ISBN 978-1-9821-5443-1

ISBN 978-1-9821-5445-5 (ebook)

For Eunice, Nunc scio quid sit amor

The plays the thing wherein Ill catch the conscience of the king.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Criminals, it turns out, are the one social group in America we have permission to hate. In colorblind America, criminals are the new whipping boys. They are entitled to no respect and little moral concern. Like the colored in the years following emancipation, criminals today are deemed a characterless and purposeless people, deserving of our collective scorn and contempt. When we say someone was treated like a criminal, what we mean to say is that he or she was treated as less than human, like a shameful creature. Hundreds of years ago, our nation put those considered less than human in shackles; less than one hundred years ago, we relegated them to the other side of town; today we put them in cages. Once released, they find that a heavy and cruel hand has been laid upon them.

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow

America by the early twenty-first century, had, in disturbing ways, come to resemble America in the late nineteenth century. In 1800 the three-fifths clause gave white voters political power from a black population that was itself barred from voting, and after 2000, prison gerrymandering was doing exactly the same thing in numerous states across the country. After 1865, African American desires for equality and civil rights in the South following the American Civil War led whites to criminalize African American communities in new ways and then sent record numbers of blacks to prison in that region. Similarly, a dramatic spike in black incarceration followed the civil rights movementa movement that epitomized [the maximum security state prison] Attica. From 1965 onward, black communities were increasingly criminalized, and by 2005, African Americans constituted 40 percent of the US prison population, while remaining less than 13 percent of its overall population. And just as businesses had profited from the increased number of Americans in penal facilities after 1870, so did they seek the labor of a growing captive prison population after 1970. In both centuries, white Americans had responded to black claims for freedom by beefing up, and making more punitive, the nations criminal justice system. In both centuries, in turn, the American criminal justice system disproportionately criminalized, policed, and forced the labor of incarcerated, disenfranchised African Americans in ways that wrought incalculable damage both in and outside of Americas penal institutions.

Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy

Go down, Moses

Way down in Egypts land

Tell ol Pharaoh to

Let my people go!

Go Down, Moses (Let My People Go!), African American spiritual

one The Call

When you try to stand up and look the world in the face like you had a right to be here, you have attacked the entire power structure of the Western world.

James Baldwin

O n September 5, 2013, I pulled my old Volvo wagona bumper sticker reading This is the Rebel Base stuck on the back by my wife, a Star Wars faninto the parking lot at East Jersey State Prison in Rahway, New Jersey. I had taught college-level courses in New Jersey prisons for the past three years. But neither my new students nor I had any idea that night that we were embarking on a journey that would shatter their protective emotional walls, or that years later our lives would be deeply intertwined.

I put my wallet and phone in the glove compartment, emptied my pockets of coins, and dumped them in the console between the front seats. I made sure I had my drivers license. I gathered up my books, plays by August Wilson, James Baldwin, John Herbert, Tarell Alvin McCraney, Miguel Piero, Amiri Baraka, and a copy of Michelle Alexanders The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. I locked the car and walked toward the maximum security mens prison, past the telephone poles that dotted the parking lot, each topped with two square spotlights.

East Jersey State Prison in Rahway was shaped like an X. At its center was a massive gray dome with boarded-up windows, surrounded at its base by a ring of oxidized copper. The wings of the prison stretched out in four directions from the dome. The brick walls of each wing were painted a dull ochre color with off-white patches. There were seventeen oblong windows on each wing with white metal bars. Turrets with what looked like brass spikes on top stood at the far end of these brick wings. The walls were covered with patches of ivy. The dull black roof was peaked and discolored by a patchwork of darker and lighter sections from repairs. Directly over the entrance to the prison, below the dome, was a guard tower constructed of Plexiglas windows. At the base of the guard tower were large yellow letters, EJSP, set against a blue background. The prison complex was ringed with cyclone fencing topped with bright, shiny coils of razor wire. At the front entrance of the prison, on the left, stood a chrome-colored communications tower with antennas.