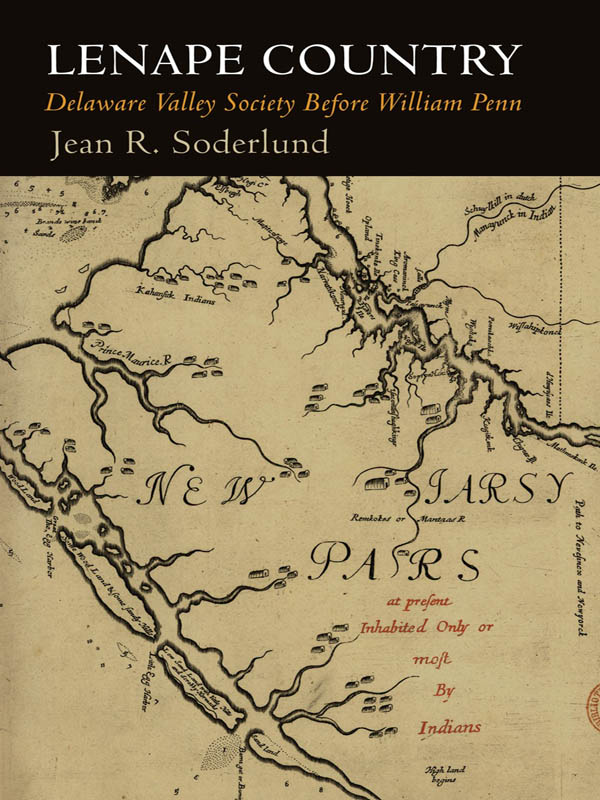

Lenape Country

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series editors:

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown, Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

LENAPE COUNTRY

_______________________________________

Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn

JEAN R. SODERLUND

Copyright 2015 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved.

Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Soderlund, Jean R., 1947

Lenape country : Delaware Valley society before William Penn / Jean R. Soderlund.1st ed.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4647-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Delaware River Valley (N.Y.-Del. and N.J.)History17th century. 2. Delaware IndiansDelaware River Valley (N.Y.-Del. and N.J.)History17th century. 3. Delaware River Valley (N.Y.-Del. and N.J.)Ethnic relationsHistory17th century. 4. Delaware IndiansDelaware River Valley (N.Y.-Del. and N.J.)Government relationsHistory17th century. 5. Delaware River Valley (N.Y.-Del. and N.J.)Social conditions17th century. 6. Indians of North AmericaHistoryColonial period, ca. 1600-1775. I. Title. II. Series: Early American studies.

F157.D4S68 2015

974.9dc23

2014007128

For Rudy

CONTENTS

__________

NOTE ON THE TEXT

__________

The English and Swedes continued to use the Julian calendar in the seventeenth century, while the Dutch had adopted the newer Gregorian calendar. The calendars were different by ten days, and the Julian New Year began in March, so that, for example, an English document dated January 3, 1667, would be January 13, 1668, under the Gregorian calendar. While accounting for these differences in analyzing evidence, I have kept the original dates when citing documents.

When I quote from English-language sources that were written prior to the nineteenth century, for better understanding I have modernized spelling and capitalization (but without altering the names of people and places); changed use of the thorn (for example, ye) to the intended word the; lowered superscript letters to the line; expanded abbreviations; and changed punctuation only when necessary for clarity. When I quote from translations of Dutch and Swedish documents, I have not altered the text.

Introduction

In May 1672, while traveling north through the English colonies in eastern North America, the founder of Quakerism George Fox and fellow missionaries arrived in New Castle, the small capital of the Delaware colony inhabited mostly by Dutch and English colonists. The town stood on the west bank of the river that the Lenapes, the Native Americans who dominated the region, called the Lenapewihittuck (now Delaware River). Fox and his companions quickly crossed the river, hiring Lenape guides who led them through the fertile lands of what is now southwestern New Jersey and the Pine Barrens farther east. Fox wrote to Friends in England that as they passed through the woods, sometimes we lay in the woods by a fire and sometimes in the Indian cabins, through the bogs, rivers, and creeks and wild woods we passed. I came at last and lay at one Indian kings house and he and his queen received me lovingly and his attendants also and laid me a mat to lie upon, a very pretty man and then we came to another Indian town where the king came to me and he could speak some English and he received me very lovingly and I spake to him much and his people and they were loving.

Fox and his associates called the Lenapes territory the Indian Country, recognizing the Natives sovereignty over the land. They described to colleagues in England a land still dominated by Lenapes despite the settlements of Swedes and Finns along the river, the Dutch/English town of New Castle, and Quaker villages of Middletown and Shrewsbury near the Atlantic shore. The hospitality of Lenapes saved Fox and his companions from sleeping under the open sky in terrain they considered a wilderness. The Quaker leader distinguished between the settlements of Lenapes who treated him lovingly and the wild woods full of bogs and rivers to cross, recognizing the Lenapes authority while appreciating their kindness. He spoke several times to the Natives about religion but reported no success in convincing them to Quakerism. They rejected his spiritual authority as he depended on them for food, direction, and shelter.

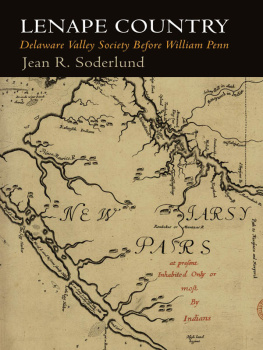

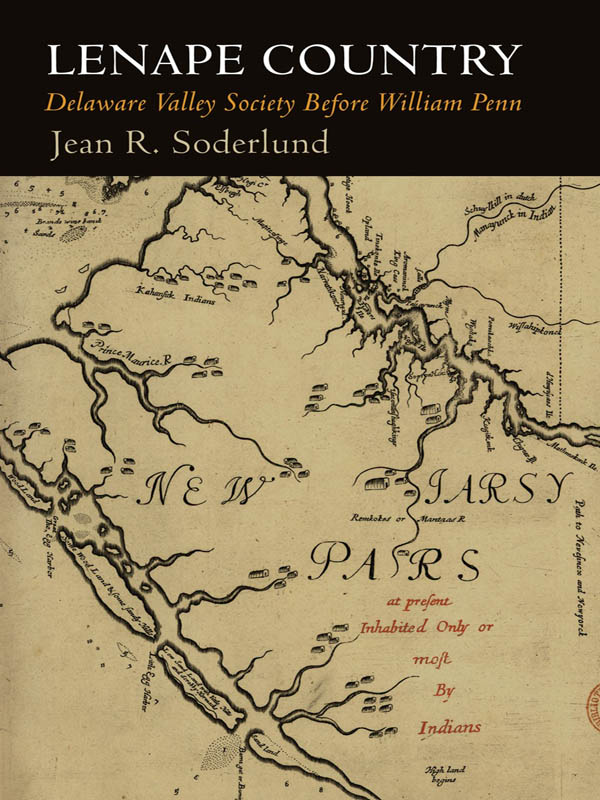

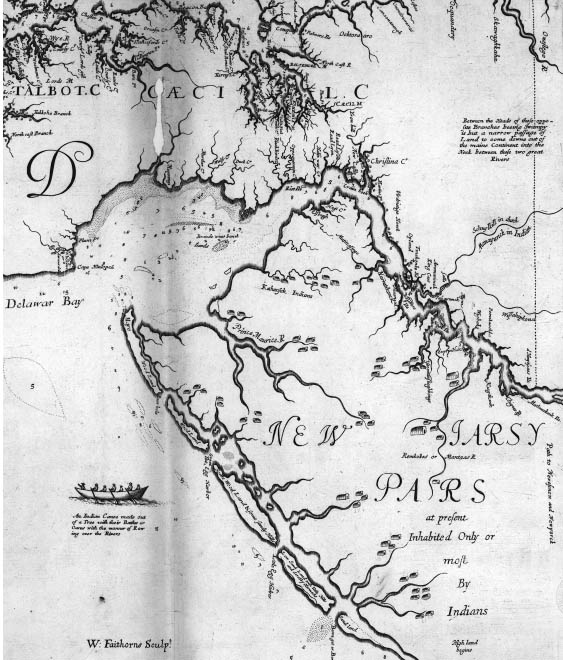

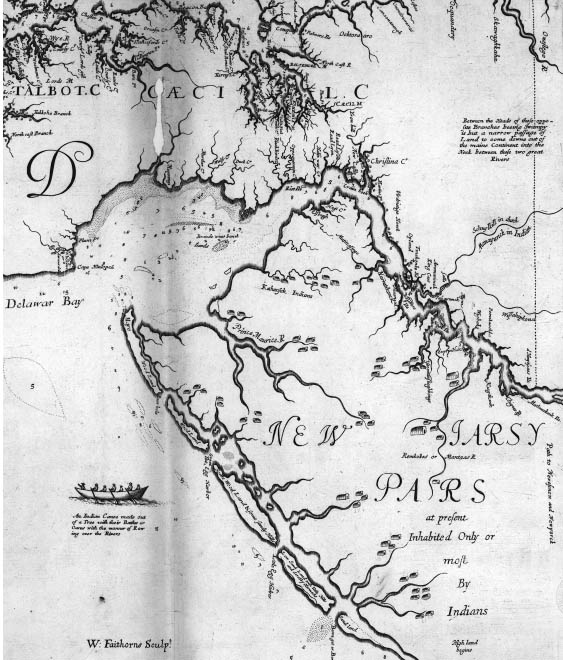

The Lenapes firm grip on south and central New Jersey is clear in a map from 1670 created by a merchant named Augustine Herrman, who had settled in New Amsterdam in 1644 and then established his plantation, Bohemia Manor, on the Maryland eastern shore in 1661. Herrman labeled the country from the Lenapewihittuck to the Atlantic Ocean as at present inhabited only or most by Indians, and he drew Lenape towns adjacent to many rivers and streams emptying into the Lenapewihittuck and the sea. Various Lenape people populated the territory as illustrated in the map (see

Notwithstanding its acknowledgment of the Natives continued presence and power in the region, Foxs report to English Friends about his journey through Lenape country helped to establish the mythology that the early Delaware Valley was a wilderness inhabited by generally friendly Indians and some scattered colonists. From his few weeks in the region, Fox described a segmented society, with Lenape towns entirely separate from Swedish, Dutch, and English villages. In this short time he learned little about the society the Lenapes, Swedes, Finns, and other Europeans had built together since European arrival, and he thus gave the impression to William Penn and other Friends in England that the Lenapes domain was ripe for Quaker colonization. Foxs narrative has given impetus to the legend that the Delaware Valley was a blank slate on which Penn and the Quakers first brought peace and justice to the Lenapes. For the Quaker founders of Pennsylvania, their descendants of the mid-eighteenth century, and historians in subsequent centuries, Delaware Valley history began in 1681 when Penn received his charter from Charles II. In creating and perpetuating this founding myth, colonists and scholars have credited Penn with efforts to form an open, tolerant society that dealt honestly and amicably with the Lenapes and other Natives. He pledged to pay a fair price for their land and to avoid the bloodshed that destroyed Native and European settlements elsewhere in eastern North America.

Figure 1. Augustine Herrman,

Next page