Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Ann

Who shared and sustained this journey

Of books and life

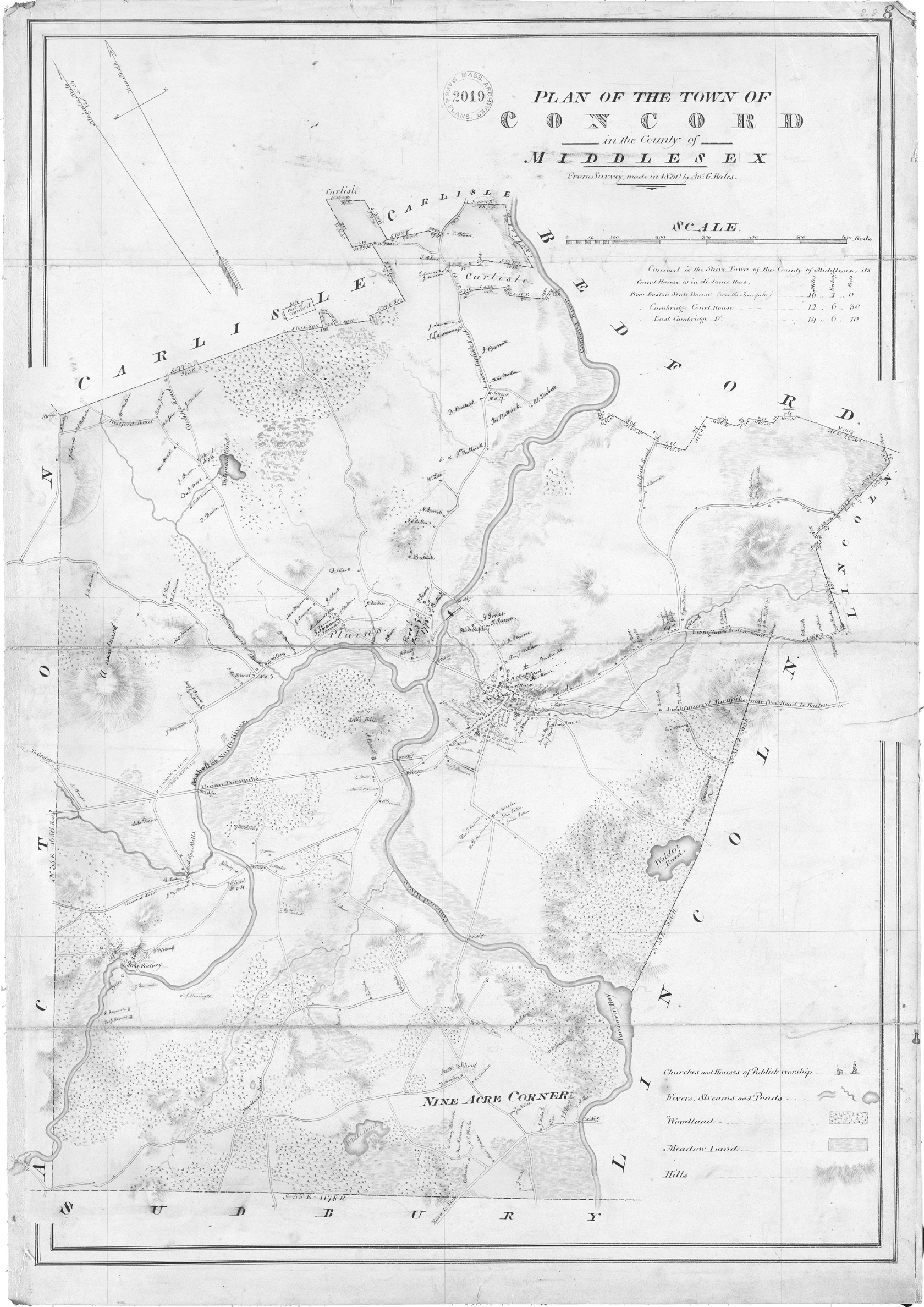

JOHN G. HALES , Plan of the town of Concord, Mass. in the county of Middlesex (1830). This map of Concord in 1830 highlights the thickening of settlement in the central village, the extension of highways east into Cambridge and Boston and west and north into the countryside, and the growth of water-powered manufacturing along the Assabet River in the southwest. Note the prominence of Walden Pond in the southeast. (Courtesy Massachusetts Archives)

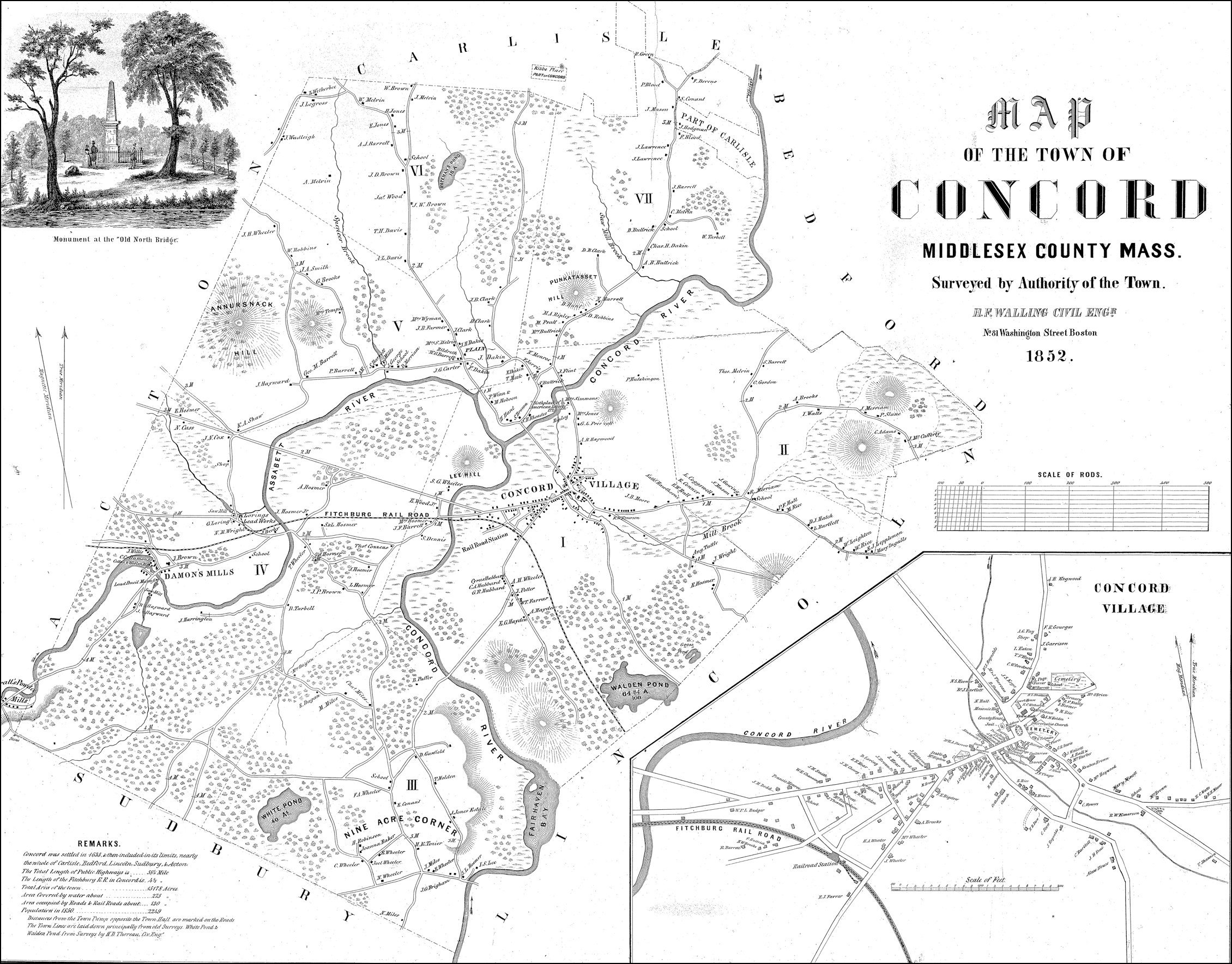

Map of the Town of Concord, Middlesex County, Mass. (1852), surveyed by H. F. Walling, a civil engineer. The coming of the railroad is evident on this map of Concord, showing the route of the Fitchburg line as it enters the town at the edge of Walden Pond, heads north into the central village, and then turns west to pass the Damon textile mill before crossing into neighboring Acton. The map indicates each of the school districts, and the inset image highlights the association of Concord with the monument at the Old North Bridge. (Courtesy Concord Free Public Library)

There can be no true history written until a just estimate of human nature is holden by the historian.

RALPH WALDO EMERSON,

Philosophy of Modern History, December 8, 1836

Wherever men have lived there is a story to be told, and it depends chiefly on the story-teller or historian whether that is interesting or not.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU,

March 18, 1861

American individualism found its strongest voices in the nineteenth century among the New England Transcendentalists, and none more so than Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. From his ancestral home of Concord, Massachusetts, Emerson summoned his countrymen to free themselves from bondage to the past and refuse unthinking conformity to contemporaries. Trust thyself, he urged; seek inspiration in nature; realize your infinite potential. Through such spiritual journeys, people of all sortswomen as well as men, Blacks as well as whites, poor as well as richcould tap their inner genius and build together an original American culture, independent of the errors and injustices of the Old World and true to the ideals of liberty and equality at the heart of the democracy that the break with Britain had left unfulfilled.

Starting in the mid-1830s, Emerson preached this stirring message in Boston and vicinity and at home in Concord, and over the ensuing decade he extended his reach on the lecture circuit to audiences across New England, in the leading port cities of the Northeast, and as far south as Baltimore. He was not alone nor initially in the forefront of the Transcendentalist movement; well into the 1840s, even as his literary reputation was growing in England, he remained a provincial figure in his native land.

No one attended to his words or felt his influence more fully than his younger townsman Thoreau, the only native son among the Concord writers, who, after graduating from Harvard in 1837, became his disciple and protg. Coming of age a generation after Emerson, Thoreau heeded the masters call for self-reliance, cultivated his own voice and vision by the shores of Walden Pond, and fashioned a classic account of how to live simply and sincerely, in harmony with nature. Walden continues to inspire today as a model of Transcendentalist individualism and a foundation text of the environmental movement. Although he lived alone, in the woods, a mile from any neighbor, Thoreau never lost sight of his townspeople, and through his strenuous critique of their way of life, he put his birthplace on the literary map. He tightened the link between Transcendentalism and town that his mentor had initiated. As Emerson gathered thinkers and reformers in his orbit, as Margaret Fuller arrived for extended stays, and as Nathaniel Hawthorne and the Alcotts took up residence, Concord gained notice as a literary center, and it soon came to symbolize the social ferment and the intellectual iconoclasm of the age. The town has been celebrated as the seat of the American Renaissance in literature and art during the decades before the Civil War. The writer Henry Adams dubbed Transcendentalism the Concord Church. It sheltered a faith he could not adopt but whose appeal he could not deny. So it was for many New Englanders then and now, within and beyond the town, and for readers all over the United States and the world.

Why Concord? Was it simply the accidents of birth and geographyEmersons familial antecedents, Thoreaus native origin, plus proximity to Bostonthat made the town a literary center? Or was the community fertile ground for novel ideas? One popular account has it that Concord was the home of two revolutionsthe first on April 19, 1775, when Minutemen clashed with Redcoats at the North Bridge and fired what Emerson called the shot heard round the world; the second in the intellectual awakening the Transcendentalists sparked with their rejection of European hierarchy and inequality and their vision of free individuals realizing the promise of democracy in everyday life. In this telling, the embattled farmers waged a successful war for political independence and self-government; their heirs in the 1830s and 1840s built on that achievement with an intellectual campaign to liberate American minds. The Transcendentalists thus extended what the Minutemen began, and their idealistic legacy has posed a vital challenge to our culture ever since.

That story misses a profound transition in American life. The Revolutionary generation fought for collective ends. It defended the right of towns and provinces to tax and govern themselves, and it founded a republic on the duty of citizens to serve the public good. In New England the ideology of civic republicanism merged with Puritan traditions to emphasize the interdependence of individuals and families within a common way of life. This worldview was compatible with a host of inequitiesslavery, white racism, class privilege, patriarchy and the subordination of womenand it was never without challenge, especially by libertarian arguments in favor of free markets and the right of individuals to pursue their own interests, whether in business or in religion. Nonetheless, a half-century after independence, the social web was still bindingas an idea, if not always in practice. In principle, everyone belonged to the community; none lived alone, independent of established institutions and without obligations to the neighbors.

The Transcendentalists rejected this intellectual heritage. Combining Romantic notions from Europe with the Protestant stress on personal salvation, and infusing these influences with a democratic faith in liberty and equality, Emerson put the individual first and foremost. As he saw it, every person comes into this world with a divine soul, infinite in possibility. It is the highest calling in life to dive into this inner ocean and give it expression. No other duty takes precedence, not the demands of elders, not the claims of church or state, not the obligation to be useful to society. An institution is merely the lengthened shadow of one man. Emersons purpose was to break the hold of ancient traditions and involuntary associations, so that every person could take the journey of self-discovery and be an inspiration to others along the way. Former generations acted under the belief that a shining social prosperity was the aim of men: and sacrificed uniformly individuals to the nation, he declared. The modern mind teaches that the nation exists for the Individual;for the guardianship and education of every man. Thoreau, characteristically, carried these convictions to excess. I am not responsible for the successful working of the machinery of society, he exclaimed. I am not the son of the engineer. I love mankind, he added during his sojourn in the woods. I hate the institutions of their forefathers.