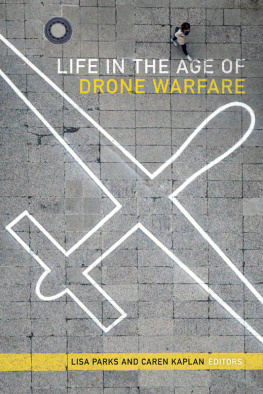

2017 Duke University Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Text design by Adrianna Sutton

Cover design by Matthew Tauch

Typeset in Sabon and Din by Westchester Publishing Services

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Parks, Lisa, editor. | Kaplan, Caren, [date] editor.

Title: Life in the age of drone warfare / Lisa Parks and Caren Kaplan, editors.

Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: LCCN 2017014021 (print) | LCCN 2017016815 (ebook)

ISBN 9780822372813 (ebook)

ISBN 9780822369585 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780822369738 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : Drone aircraft. | Air warfare. | Drone aircraft pilots.

Classification: LCC UG 1242 .D 7 (ebook) | LCC UG 1242 .D 7 L 54 2017 (print) | DDC 358.4/14dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017014021

Cover art: Drone Shadow installation by James Bridle (jamesbridle.com), Ljubljana, 2015. Photograph courtesy of Aksioma Institute for Contemporary Art.

CONTENTS

DEREK GREGORY

LISA HAJJAR

KATHERINE CHANDLER

ANDREA MILLER

LISA PARKS

CAREN KAPLAN

RICARDO DOMINGUEZ

THOMAS STUBBLEFIELD

MADIHA TAHIR

ANJALI NATH

JEREMY PACKER AND JOSHUA REEVES

PETER ASARO

BRANDON BRYANT

JORDAN CRANDALL

INDERPAL GREWAL

Life in the Age of Drone Warfare emerged through a series of dialogues between media, communication, and cultural studies scholars, artists, sociologists, feminists, geographers, journalists, philosophers, and science and technology studies specialists during the past several years. The collection began to germinate during the Drones at Home conference at the University of CaliforniaSan Diego in 2012, organized by Jordan Crandall and Ricardo Dominguez, and further evolved during the Sensing the Long War: Sites, Signals and Sounds workshop at the University of CaliforniaDavis, the Life in the Age of Drones symposium at the University of CaliforniaSanta Barbara in 2013, and the Eyes in the Skies: Drones and the Politics of Distance Warfare conference at UC Davis in 2016. We are grateful to the Militarization Research Group, the Mellon Digital Cultures Initiative, the Department of American Studies, and the Cultural Studies Graduate Group at UC Davis and the Center for Information Technology and Society, Interdisciplinary Humanities Institute, and Department of Film and Media Studies at UC Santa Barbara, whose support enabled us to deepen and expand our discussions and understandings of drone technologies and processes of militarization. We also thank Arthur and Marilouise Kroker for their vital interventions at the UC San Diego and UC Santa Barbara events. Their provocations continue to reverberate and have marked this project in numerous ways. In addition, we are grateful to all the conference, workshop, and symposium participants for their stimulating presentations and artworks, many of which are included in this book. Other scholars and activists who have supported and inspired us include Javier Arbona, M. Ryan Calo, Deborah Cowen, Lindsey Dillon, Kris Fallon, Emily Gilbert, Casey Cooper Johnson, Lopold Lambert, Nancy Mancias ( CODE PINK ), Minoo Moallem, Trevor Paglen, Marko Peljhan, Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli, Alex Rivera, Rebecca Stein, Jennifer Terry, and Federica Timeto. We also thank Abby Hinsman for editorial assistance as this project was getting off the ground.

As our ideas for the Life in the Age of Drone Warfare collection began to cohere, we were very fortunate to connect with editor Courtney Berger, who has been supportive, thoughtful, and enthusiastic throughout the editorial process. We are grateful for her commitment to this project and the manner in which she helped it come to fruition. We also thank Sandra Korn and Susan Albury at Duke University Press for their careful readings and attention to detail and for being extremely helpful editorial associates. We are indebted to this books contributors for their significant chapters, ongoing commitment to the project and the issues it addresses, and their collegiality. Our deepest gratitude goes to Andrea Miller, who worked tirelessly as an editorial assistant during various stages of the manuscripts preparation. Simply put, the project could not have happened without her myriad efforts. Finally, the project benefited from the insightful reviews of three anonymous readers, whose comments were enormously helpful as we moved the project toward completion.

Beyond those mentioned above, we would like to thank Brandon Bryant for his openness to participate in this project, despite challenges he continues to face as a veteran and whistleblower. Caren Kaplan thanks her faculty and graduate student colleagues in American Studies (especially her department chair, Julie Sze) and Cultural Studies at UC Davis for sharing their work and supporting her research interests with such enthusiasm. She also thanks Eric Smoodin and Sofia Smoodin-Kaplan for all kinds of support on the home front and Marisol de la Cadena, Inderpal Grewal, Meredith Miller, Minoo Moallem, Ella Shohat, and Jennifer Terry for their friendship and interest in this work. She also extends a big thanks to Lisa Parks for conceiving this project and getting it started before inviting her to join as coeditorworking together has been a joyful experience. Lisa Parks thanks the faculty, graduate students, and staff in the Department of Film and Media Studies at UC Santa Barbara for providing a stimulating, supportive, and fun work environment for so many years, and expresses gratitude to her new colleagues in Comparative Media Studies/Writing at MIT for creating new opportunities and a dynamic place to work. She also thanks from the bottom of her heart John Harley, Jennifer Holt, Moya Luckett, Constance Penley, Rita Raley, Cristina Venegas, and Janet Walker for their incredible friendship and support over the years, and conveys her deepest gratitude to Caren Kaplan for being an exceptional coeditor, scholar, and friend.

LISA PARKS AND CAREN KAPLAN

SINCE 2009, U.S. news media have had a virtual love affair with the drone. Celebrating the alleged novelty and flexibility of the technology, reporters have pointed to a proliferating array of quirky or surprising drone uses, ranging from pizza delivery to pornography recording, from the maintenance of energy plants to the protection of wildlife, from graffiti writing to traffic monitoring.

In addition to this flood of news features about the playful and pragmatic potentials of drones, the drone-o-rama has included a steady stream of reporting on the more somber topics of drone warfare and targeted killing. Investigative reporter Jane Mayer first broke the story about the Central Intelligence Agencys ( CIA ) drone war in Pakistan in 2009. Thus, drones are not only envisioned as a pivotal technology in U.S. counterterrorism efforts, but politicians and manufacturers have colluded to ramp up the expansion of the civilian drone sector. In 2014 digital behemoth Google purchased drone manufacturer Titan Aerospace, promising to use drones to bring Internet access to the planets most remote and underserved regions.

While some news media have played up the friendlier, neoliberal side of the technology, emphasizing its capacity to handle a multitude of tasks and, in the process, make life easier while expanding the global economy, To be sure, the drone has become a contested object. While drone strikes are routinely reported in most mainstream news outlets, what is often missing from the reportage is an understanding of the material ecologies through which drones are operationalized. These ecologies have been depicted in fictional television series such as Homeland and , films such as Eye in the Sky , and computer games like Drone: Shadow Strike and the Call of Duty series, yet the narrative logic of these media often (though not always) works to legitimate or reinforce militaristic drone use, even if providing windows of opportunity to question it.

Next page