Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

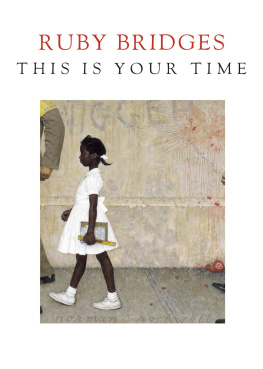

Text copyright 2020 by Ruby Bridges

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Some photographs are from the authors collection. Remaining image credits are located on .

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN9780593378526 (trade) ISBN9780593378533 (lib. bdg.) ebook ISBN9780593378540

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020944816

Cover design by Regina Flath

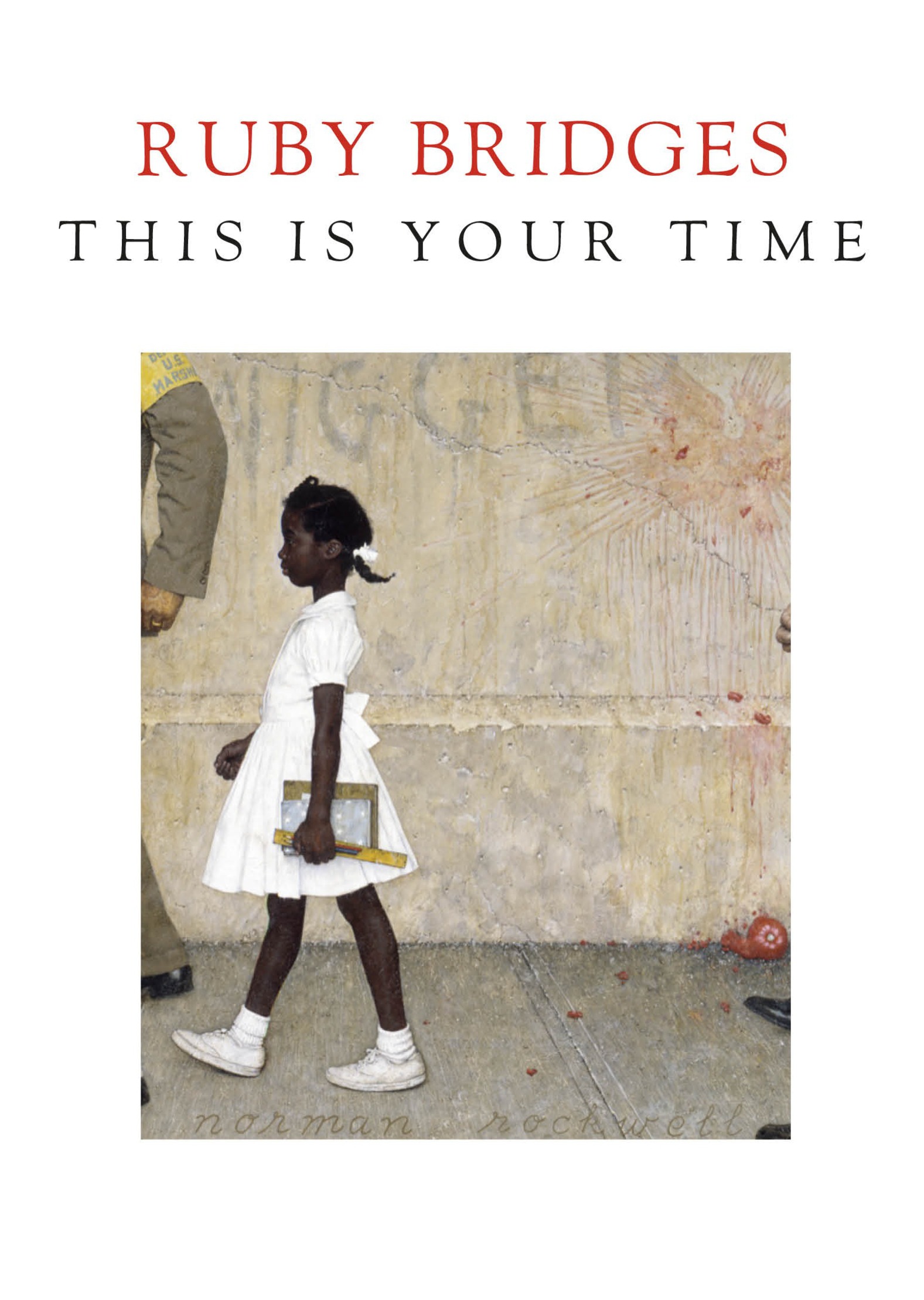

Cover art: Original art from The Problem We All Live With is in

the collection of the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA.

Image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

Penguin Random House LLC supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to publish books for every reader.

ep_prh_5.6.0_c0_r0

Contents

I dedicate this letter of peace to Congressman John Lewis, icon of the civil rights movement, with admiration. He was known as the conscience of Congress, truly an example of a soul generated by love.

Job well done, our good and faithful servant!

The torch is passed!

We have much work to do, Young Peacemakers of the World.

To the young peacemakers of America,

Sixty years ago, in 1960, my life changed forever. Although I was not aware of it, our nation was changing too. What I remember about that time, through my six-year-old eyes, is that there was extreme unrest, much like we see today. I was chosen to be the first black child to go to an all-white school, William Frantz Elementary, in my hometown, New Orleans.

I did not yet know that I had stepped into the history books.

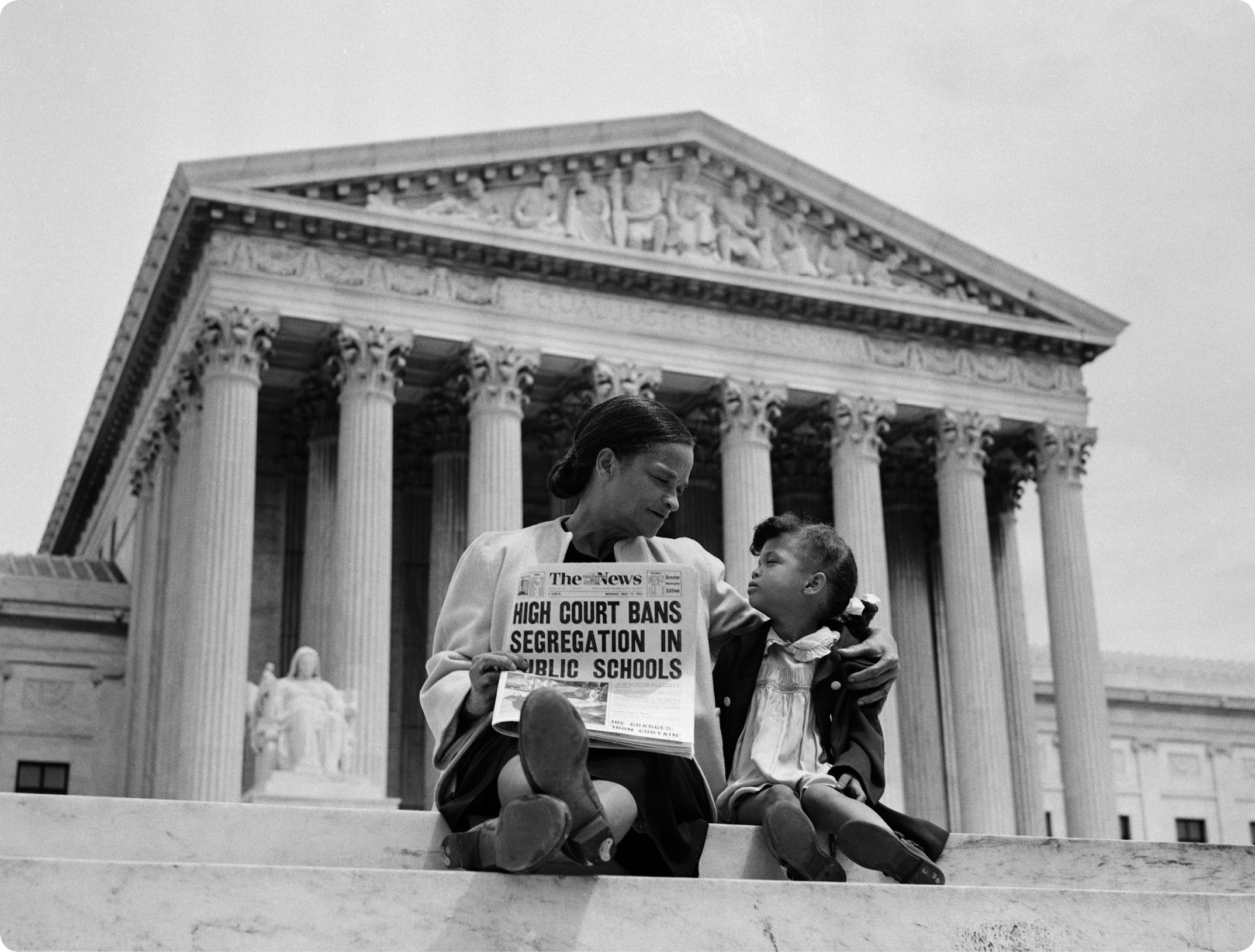

The 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education deemed racial segregation in schools unconstitutional.

For my whole first-grade year I had to be escorted to and from school by four federal marshals, under the order of the president of the United States, because people were afraid for my safety.

U.S. marshals escort Ruby Bridges from William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans in November 1960.

Going into and coming out of school every day, I walked through crowds of people yelling, screaming threats, throwing things at six-year-old me. They were against the integration of black and white children in the same school. I had been so excited to meet and make new friends at school, and was met with something utterly different and terrifying.

Angry segregationist protesters gathered daily outside Rubys school (1960).

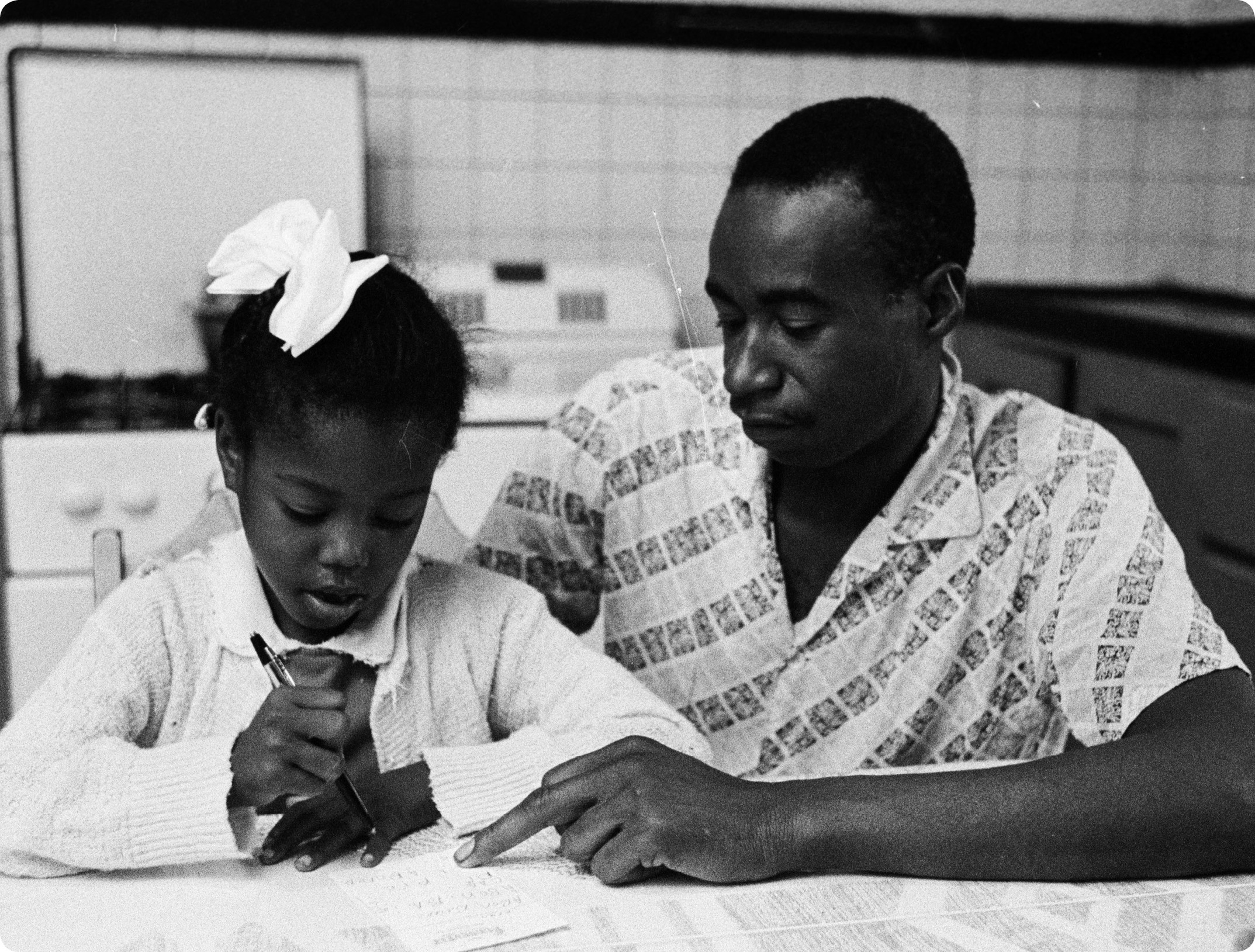

It was a difficult decision for both of my parents to agree to let me go to school along with the marshals, especially for my dad, but they knew it was necessary. My father, like most dads, wanted nothing more than to protect his little girl. But as a young black man, it was not safe for him to walk me to school.

Police officers flank the entrance for Rubys arrival on her first day (1960).

My father loved me more than I would ever know, and I felt that he was my very own hero.

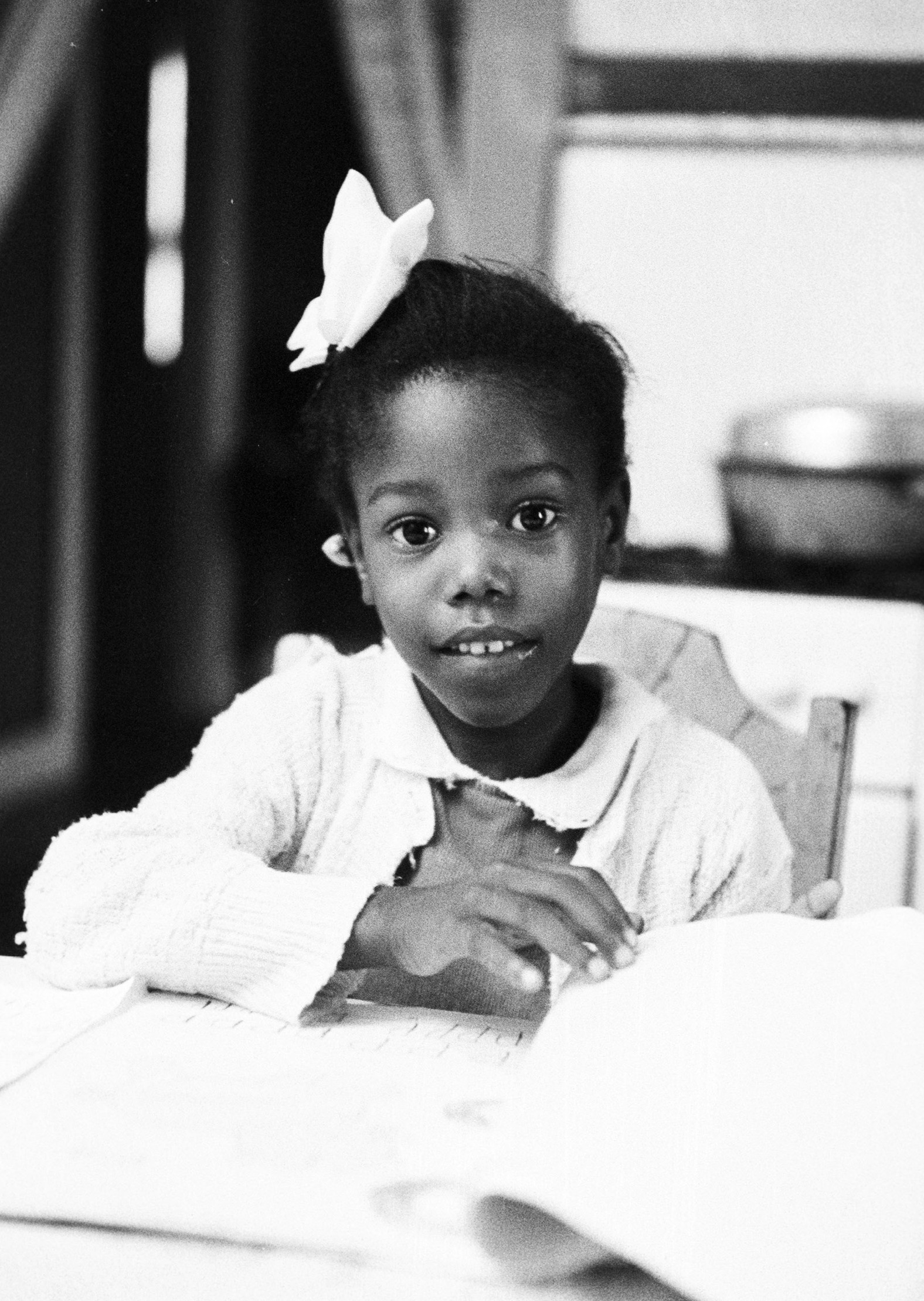

Ruby and her father, Abon Bridges (1960).

He was also a real hero, having received a Purple Heart for bravery while serving overseas in the Korean War. But he did not return to a heros welcome. There was little work given to young black men back then.

Rubys father, a Korean War veteran, in uniform.

When I arrived at this all-white school that first day, all the white parents rushed in and pulled out their kids. They didnt want their children going to school with me. But why? I didnt understand. They had never met or even seen me before now, so how could they know what kind of person I was? But none of that mattered. I dont think they even saw a child. All they saw was the color of my skin. I was black, and that meant I didnt matter.

Some teachers even quit their jobs because they didnt want to teach black children.

Parents outside William Frantz Elementary School carry a coffin holding a black doll as they protest integration (1960).

My teacher, Barbara Henry, came all the way from Boston to teach me. For the entire year she sat alone with me in that classroom and taught me everything I needed to know. She really made school fun. We never missed a day that whole year. We knew we had to be at school for each other.

Ruby and her teacher, Barbara Henry. Though the school was desegregated, white parents refused to let their children share a classroom with Ruby (1960).

I felt safe and loved, and that was because of Mrs. Henry, who, by the way, looked exactly like the women in that screaming mob outside. But she wasnt like them. She showed me her heart, and even at six years old I knew she was different. Barbara Henry was white and I was black, and we mattered to each other. She became my best friend. I knew that if I got safely past the angry crowd outside and into my classroom, I was going to have a good day.