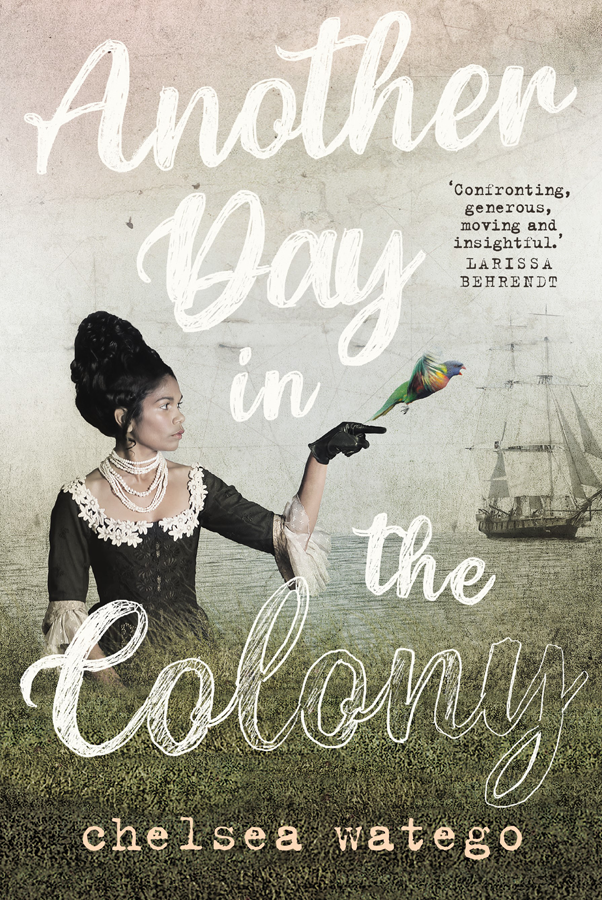

Chelsea Watego is a Munanjahli and South Sea Islander woman born and raised on Yuggera country. First trained as an Aboriginal health worker, she is an Indigenist health humanities scholar, prolific writer and public intellectual. When not referred to as Vern and Elaines baby, she is also Kihi, Maya, Eliakim, Vernon and Georges mum.

I wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose hands hold this book and pay my deepest respects to you and your country as traditional owners, whose sovereignty remains unceded and who we each remain accountable to.

This book is dedicated to Vernon Thomas Watego and Matthew Kehi-Toka Bond.

I am eternally grateful for the life, love and learning that you both have gifted me.

contents

acknowledgements

I want to acknowledge my children Kihi, Maya, Eliakim, Vernon and George, who typically experience their mums work via absence. I want to thank you for family time, sunshine songs and kitchen table conversations that made us laugh, cry and think. I am so very proud of the people you are, and Im so very sorry for the things youve had to experience; things that should never have shaped a childhood, but nonetheless did.

I want to thank my mum for always being there for me, in whatever way she could as a mother to me and grandmother to my children. I know you knew there was an incommensurability with our experiences as women and as mothers and Im so very grateful to you for never discounting or dismissing my experiences of this world. Thank you for always being there literally, holding it down and just loving me through all of the shit.

I would like to sincerely thank Dr David Singh who helped me to think about race through my experience of it, and who over the years has guided my reading and thinking through conversations often at the drop of a hat. I feel very fortunate to call you a colleague and friend and to do the work that we get to do together. Similarly, I would like to thank Dr Bryan Mukandi who Ive had the privilege to work with over many years, and who first introduced me to Paul Beattys stages of Blackness. Bryan not only read each chapter but also reads most of my work before it goes out in the world; his cautions I dont always heed, but his time and thoughts I always value.

I must acknowledge Professor Mark Brough who has been instrumental in my academic career, starting out as an undergraduate student and research assistant, to postgraduate studies and facilitating my first academic appointment. I never understood what an academic was, nor had I ever aspired to be one; it was your generosity that defined for me what an academic could be and do, in the work, and for others.

I also want to thank my mob who have grounded me culturally and intellectually and, same time, have had my back when I needed, always bringing Black love and laughter to my life: Ali Drummond, Lisa Whop, Karla Brady, Amy McQuire, Kevin Yow Yeh, Carly Wallace, Paola Balla, Murrawah Johnson, Janet Stajic, Teila Watson and my sister Simone Watego, thank you for all that you do, including what you do for me, in just getting it. In addition Im a beneficiary of being part of a most generous, caring and clever intellectual community so I wish to thank my friends Helena Kajlich, Alissa Macoun, Liz Strakosch, Debbie Kilroy and Anna Carlson for being there in so many ways for me and for mob.

Finally, I would like to thank Uncle Shane Coghill and Aunty/Dr Lilla Watson for mentoring and modelling the kind of Indigenous intellectual sovereignty I can only aspire to. Uncle Shane is a Goenpul Yuggera man and an Original Inala Boy who has cared for me and our family in ways that I cant properly do justice to here. Uncle Shane did not teach me about sovereignty as a theory, but as something embodied, every day and everywhere. I am most grateful for the strength he has given me, particularly when I felt at my weakest. As it happens, it would be those times that Uncle Shane would always appear. I feel like he has been that boxing coach in the corner of the ring, always in the ear of his beleaguered fighter between each round, saying all the things needed for that fighter to jump up when the bell rings despite the pain and doubt felt in that body. With Uncle Shane in my corner, getting up felt less of an act, and more of a determined and deliberate form of action. Thank you, Uncle, for insisting I remember my strength as Yugambeh, never losing sight of what it is to be sovereign and never underestimating the power that matriarchal mob hold, as we stand in relationship with each other and the surrounding peoples of South East Queensland.

Aunty/Dr Lilla Watson is a Birri Gubba and Gungalu scholar who I first met as a young student at a UQ graduation ceremony while she was serving as a member of Senate. I didnt know her at the time, but she encountered me among a sea of whiteness and told me she was proud of me. I remember her handing me a hanky of hers to wipe my tears and to this day I am most fortunate to have the opportunity to sit at her kitchen table these decades later, to listen, to learn, to laugh and, still, to cry (even though she gammin tells me not to!). Aunty Lilla was very much a part of the thinking in this book and those yarns at her kitchen table, much like the ones I grew up having with my father, have shaped how I think of myself and my place, not just in the colony, but on my country.

Theres a particular conversation I had with Aunty Lilla that didnt find its way into any of the chapters, but profoundly shifted the terms of reference of this book. It was the day after the thirtieth anniversary of the handing down of the report from the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. I had travelled to Sydney at the invitation of sister Gwenda Stanley to participate in a panel conversation with family members who had lost loved ones in custody. It was a day that felt more violent than most days in the colony, having heard these accounts firsthand, and in such detail. I was left feeling numb and broken. The following morning, I flew home and landed at Aunty Lillas kitchen table, with the draft manuscript of this book. It was in this state that I was gifted with her most generous critique, one that revealed the limitations of my frame of reference but, in what it offered, healed the very despair I had been grappling with.

This book initially was one that strategised survival but, having read the manuscript, Aunty Lilla looked me in the eyes and said, Chelsea, we are not survivors. We are more than that. Consequently, I reconfigured my thinking to be less about surviving, and to instead centre upon our living. Similarly, Aunty Lilla called into question my reliance upon resistance. Resistance, she felt, betrayed the groundedness of Indigenous sovereignty. We havent moved, she said. We are holding our ground and they just keep battering us, but we are standing strong. So in lieu of resistance, I have talked about Indigenous presence as one of insistence and persistence. You see when our sovereignty is framed as resistance, as agitation, as aggression, it is as though we are the antagonists. But we are not. And the violence we encounter for having held our ground is not of our making. We must remember that.

The final terms we talked about were settlers and settler colonialism, which appeared to Aunty Lilla to minimise the violence of this particular form of colonialism there is little settling about a relationship in which the colonisers never leave. So, I speak instead of colonisers and, at Aunty Lillas suggestion, colonial settlerism. I am compelled to tell of this encounter to honour and acknowledge Aunty Lillas intellectual work, for it is hers, not mine. In doing so I also want to show how insightful, how generous, and how important the critique of Aboriginal women is in this place.