Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

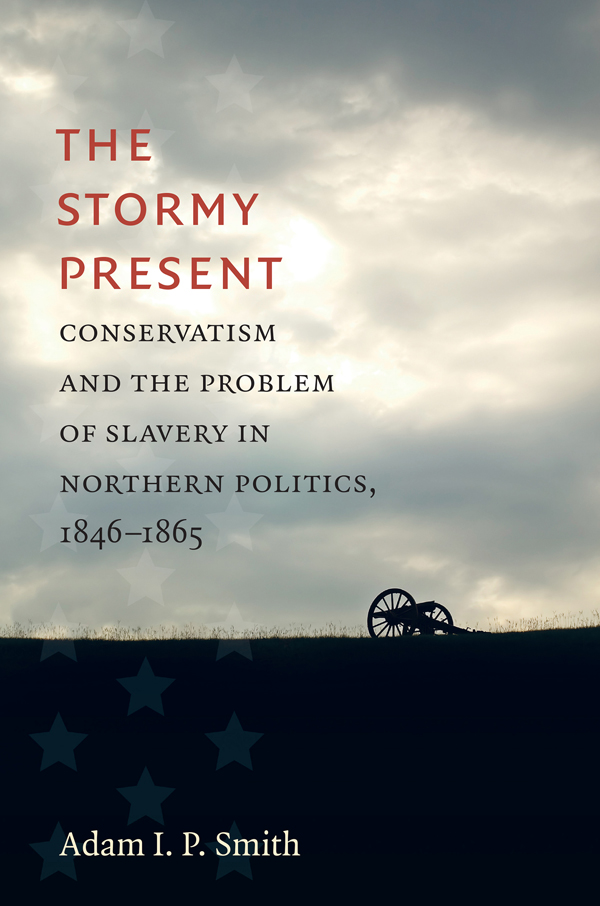

The Stormy Present

CIVIL WAR AMERICA

Peter S. Carmichael, Caroline E. Janney, and Aaron Sheehan-Dean, editors

This landmark series interprets broadly the history and culture of the Civil War era through the long nineteenth century and beyond. Drawing on diverse approaches and methods, the series publishes historical works that explore all aspects of the war, biographies of leading commanders, and tactical and campaign studies, along with select editions of primary sources. Together, these books shed new light on an era that remains central to our understanding of American and world history.

ADAM I. P. SMITH

The Stormy Present

Conservatism and the Problem of Slavery in Northern Politics, 18461865

The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill

2017 Adam I. P. Smith

All rights reserved

Set in Arno Pro by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Adam I. P., author.

Title: The stormy present : conservatism and the problem of slavery in Northern politics, 18461865 / Adam I. P. Smith.

Other titles: Civil War America (Series)

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2017] | Series: Civil War America | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016055625 | ISBN 9781469633893 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469633909 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Northeastern StatesPolitics and government19th century. | ConservatismNortheastern StatesHistory19th century. | SlaveryUnited States. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Causes.

Classification: LCC F 106 . S 598 2017 | DDC 973.7/11dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016055625

Jacket illustration: istockphoto.com/BCWH.

For Caroline, Rosie, Eleanor, and Lucy

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present.

Abraham Lincoln, 1862

Contents

Preface

Imagine you lived in a small town in upstate New York, or Ohio, or Pennsylvania in 1848. It is a town like many others, with a main street that is dusty in the summer and a quagmire in winter. Its principal features are a courthouse, a tavern, and several churches, one with a striking spire. Most of the houses have two or three rooms on a single floor and are built of wood, but there are some brick houses too, some three stories high. You or a member of your family might run a dry-goods store or work as a bookkeeper for a local merchant; or perhaps you are a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse, your salary paid by local taxpayers under the terms of a recent state law establishing a public education system.

You and your neighbors are prospering, on the whole. It has been more than a decade since the last major economic downturn. True, one of your relatives lost his farm when he failed to keep up the mortgage repayments, but he has recently borrowed the money for a steamship passage to California and new opportunity. Indeed, your town has grown rapidly in the last few years and some of the newcomers have arrived from Germany, England, or Ireland, founding new churches, speaking in accents you dont at first understand. You werent born in the county yourself, but you feel like a well-established presence now: your children were born hereone is buried in the local cemeteryand you like to feel you know whats going on.

Now imagine: recently, a pugnacious young man with some college education and political ambitions has established a new daily newspaper to rival the longer-established organ. You dont always agree with the editors fiery editorials, but the new paper seems to have better and quicker access to reprinted articles from other states and evenvia reprinting stories in the New York Tribune from Europe, which is gripped by political turmoil. The news sparks interesting conversation among neighbors. One of the newcomers speaks personally of having witnessed the army opening fire on protestors in a German town. Another is a Chartist from Yorkshire, who claims to have been thrown out of his job in a textile mill for political organizing and who speaks eloquently and at length about the rapaciousness of the landed classes back home. There are landed gentry here, of a kind, but at least they dont have titles.

Everyone in your town is white, but occasionally there are rumors that a family of fugitive slaves from south of the Ohio River is being hidden in the home of one of the local pastors, an outspoken abolitionist. Sometimes your own minister talks of the universal desire that the institution of slavery should utterly cease in this land of freedom and you nod in agreement. But you nod also when he adds that slavery has law on its side and that any abrupt legislation ending it would bring evils to the country scarcely less palatable than slavery itself. More often his Sunday sermons focus on the need for a religious patriotism as the foundation of a virtuous republic. The love of country, your minister is fond of saying, is required by Holy Religion, but even more so since we have a country so preeminently deserving of affection, so blessed by Divine favor.

Apart from the Sabbath, your life is filled with work and largely bounded within the ten miles or so around your town. The journey to Philadelphia or New York used to take a couple of weeks on pitted roads or by lake and canal, but now the cuttings and embankments for railroads are being builtmainly by the Irish laborers who sometimes cause drunken scenes. You sense that your world is undergoing a transformation never seen by any generation. You feel blessed to live in the freest country on earth. You want to keep it that way.

If you lived in that small town in 1848, the next decade and a half would force you to make difficult political choices, all the while worrying that your prosperous, free society was under threat. In the days to come, your town will be convulsed by politics: some of your friends join secret anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant lodges run by the Know-Nothings. There will be violent attacks on a visiting abolitionist speaker and emotional meetings opposing the extension of slavery into Kansas. Old parties will collapse and with them old certainties. In 1850, it would have seemed impossible to imagine having to make the decisions, commitments, and sacrifices that will be pressed on you in the coming years. In those days, at times you will feel never more alive, and never more determined to do your religious and patriotic duty for your forefathers and for the generations to come. At other times, you will feel despairing of the future. And often you are simply unsure and confused by the choices before you.

Politicians sometimes seem too mired in corruption to be trusted. The stump speakers you hearsome of them the leading men of the county, others who say theyre fresh from the people and untainted by office holdingalmost all describe themselves as conservatives. They all say theyre Unionists and offer solutions that they claim will avoid the nightmare of disunion. Yet the politicians, the newspaper editors, and even some of the preachers you hear also castigate their opponents for having abandoned the principles of liberty. You worry about agitators who use violent language, and the blind partisanship and fanaticism that prevent compromise. You had grown up believinglike all your family and neighborsthat the Constitutions genius was that it mitigated conflicts by acknowledging the different interests of the far-flung republic. And the political institutions of the country, the rituals of national remembrance such as July Fourth speeches, together with churches and schools, had alwaysup until nowbeen sources of authority establishing the boundaries within which your free society could flourish. Now those institutions seem at war with one another, exaggerating differences rather than easing them. The sensibility of your society seems to shift around you. There is, you have come to feel, a far tougher, less tolerant, more confrontational pitch to public life; compromise had once been a virtue, but now self-described conservatives are decrying it as submission. And wheneventuallythe South launches a rebellion to break up the government and opens fire on the national flag, the question you will face is what price is worth paying to restore the Union.