EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Daniel K. Richter and Kathleen M. Brown, Series Editors

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Copyright 2006 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Middleton, Simon (Simon David).

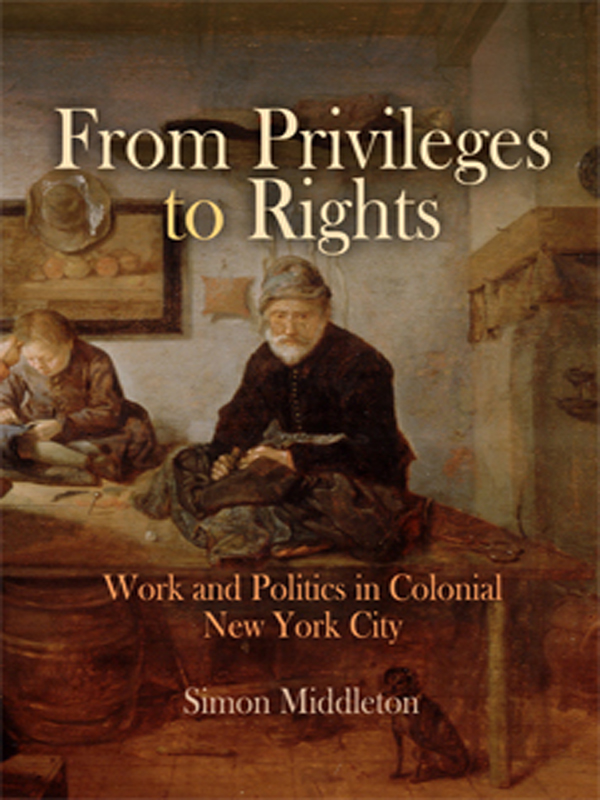

From privileges to rights: work and politics in colonial New York City / Simon Middleton.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8122-3915-7

ISBN 10: 0-8122-3915-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. ArtisansNew York (State)New YorkHistory. 2. EntrepreneurshipNew York (State)New YorkHistory. 3. Working classNew York (State)New YorkHistory. 4. New York (N.Y.)HistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775. I. Title. II. Series.

HD2346.U52N545 2006

331.7940974109033dc22

2005042441

For Carolyn, Betsy, and Rosie

Illustrations

Introduction

When I began the research for this book, I had a fairly clear idea about where my project might fit within an established historiography. Three decades of social and labor history had provided a persuasive account of the transformation of colonial American artisans into waged workers during a contested transition to capitalism. Building on the work of European scholars, American historians traced the rise of a market society and the decline of customary practices, craft pride, and workshop traditions that were thought to have once forged a powerful social bond between masters, journeymen, and apprentices. This decline was accompanied by a worsening of artisanal working conditions and material fortunes that fostered novel forms of republican political protest and ultimately class struggle. It would be difficult to exaggerate the influence of this view in labor and social history in the last four decades.

With this in mind I set out to examine the artisanal trades in early New York City, suspending my inquiries at 1760 so as to avoid the gravitational pull of the American Revolution that already held so many excellent studies in its orbit. After several, mostly unsuccessful, forays into the archives I began to appreciate why we knew so little about artisanal work in the earlier colonial period: court minutes and published sources frequently mentioned tradesmen who brought disputes before the magistrates, registered as freemen, paid taxes, or served in the militia; these registers and lists provided the raw data for several sociological analyses of the distribution of wealth, ethnic composition, and occupational structure of New York's skilled workforce.

The Mayor's Court Papers revealed that city artisans served a local market and that labor shortages made gainful employment generally easy to find. However, the complaints and related documentsbonds, promissory notes, bail agreements, and witness depositionsalso disclosed that as early as the third quarter of the seventeenth century the fortunes of ordinary working men and women were intimately bound up with the Atlantic trade and the commercial development of the city's rural hinterland. Tradesmen divided their energies between skilled work and all manner of commercial enterprise, relying on credit to pursue whatever opportunity offered the best return. They participated in the export of furs, tobacco, and plantation supplies and purchased imported cloth and household goods for resale in the city and its environs. They financed speculative ventures, and bought, sold, and rented property; they farmedraising crops and livestock for local and export marketsand provided food, drink, and lodging for paying guests. In these and other endeavors, tradesmen were far from independent. They relied on wives, family members, slaves, and waged workers for labor and on partners and patrons for credit, capital, and access to customers for their finished goods and services. Indeed, the closer one looked, the more interdependent and impermanent artisans fortunes appeared. Skilled practitioners working in all areas experienced success and failure, and their commercial strategies seemed to be directed more toward the short-term opportunism of the economy of a bazaar than the orderly pace of craft work usually associated with preindustrial colonial towns. Indeed, by the early eighteenth century the commercial logic of the city's trading economy encouraged artisans to undertake the reverse of what has previously been considered their usual working practice: rather than mastering one trade in a workshop dedicated to the production of bespoke products for local customers, artisans participated in whatever enterprises and markets promised profits with a minimum of risk.

From the Mayor's Court Papers, it seemed increasingly likely that the view of a general and fundamental shift from independent, amenable, and reasonably rewarded craft work to dependent, alienated, and penurious wage work, which had long figured in studies of early industrialization and class formation, had mischaracterized the experience of earlier skilled workers and overestimated the transformative effects of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Rather than continuing to take late eighteenth-century tradesmen at their word, giving credence to their representations of a collective past, my task became the recovery of the world of New York City artisans that preceded the association between skilled work, independence, and virtue that informed the small-producer, republican tradition in the era of the American Revolution and subsequently.

The investigation of this earlier urban scene required that I broaden my focus beyond artisans commercial activities to consider the relationship between the practice and perception of skilled work, artisanal status, and community rights in New Amsterdam and early New York City. As a wealth of historical and anthropological studies have shown, work has ever been more than a material and technical pursuit bounded by considerations of location and resource. The organization of productive capacities and employment of skills is also a social process that requires the justification of authority and interests in terms of norms and expectations that change over time, norms and expectations that are only fully intelligible when set within the wider context of contemporary political and legal discourses. Moreover, the universality and mundanity of work affords it a particular significance in the determination of social and cultural meanings for ordinary men and women: the daily repetition of simple tasks and replaying of social roles relieves individual doubts and uncertainties regarding the arbitrary assignment of political and cultural meanings by making such meanings appear routine, normal, and even natural. Above all, the function of work as the source of basic material provision in some cases and of comfort and considerable wealth in others grants it a defining role as the human activity in which aspirations confront possibilities and, once tempered in light of perceived limitations, quickly harden into realities.