For Mitra and Mila

Contents

You follow drugs, you get drug addicts and drug dealers. But you start to follow the money, and you dont know where the fuck its gonna take you.

Detective Lester Freamon, The Wire

The densely terraced streets surrounding Crewe Alexandras Gresty Road stadium were eerily and uncharacteristically quiet. It was match day, a Sunday, but there was none of the pageantry that marked the usual pre-game build-up. There were no vans selling pies and sausages; no programme stands. There seemed to be no fans at all.

But at the corner of the stadium, inside a red door in a tiny, unmarked red-brick building opposite the Gresty Road Chip Shop (Under New Management), Harold Finch was keeping a flame alive. The 88-year-old was as busy as ever on match day, opening his programme and badge shop which he had run for over 60 years.

Inside, the tiny room was the closest thing you could find to a footballing time machine. Atop two tables were stacks of old, weathered football programmes, arranged in neat piles, dating back to the start of the twentieth century. A third, manned by Harolds son, was taken up by a glass and wood case displaying pin badges commemorating matches long forgotten. Im officially the club historian and Ive seen well over 3,000 games, said Finch proudly, wearing a Crewe Alexandra training top, grey hair swept back. I first started watching Crewe as a supporter on 10 March 1934, he explained. Crewe Alexandra 42 Accrington Stanley.

There are few people alive today who can vividly recall football matches that span nine decades, but Harold is one of a shrinking club. He has travelled to almost every football league ground past and present. There are only two missing to complete the full set: Manchester Citys Etihad Stadium, 40 miles north of Gresty Road, and Arsenals Emirates Stadium, both symbols of a game so far removed from Crewe Alexandra v Accrington Stanley in 1934 that they might as well exist in parallel universes. The club has been in existence since 1877, making it one of the oldest in the world; the stadium has sat on this spot since 1907, squeezed in between rows of red-brick terraced housing to the west, and the West Coast main line on the other side. The railways provided the backbone of Crewes industry and working-class fan base, bequeathing the club its nickname: The Railwaymen. Harold himself had worked on the railways.

Today, the club play in League One, the third tier of English football, and have never made it to the top division. They once spent twenty straight seasons in the old fourth division. As football emerged from the dark days of the 1980s into the shiny new world of Premier League all-seater stadiums and wealthy benefactors, Crewe Alexandra retained its old identity. It was a community club with an ownership structure of old: local businessmen done good, investing in their clubs almost as an act of philanthropy rather than for profit or a short cut to fame and success. The clubs chairman, John Bowler, had returned to Crewe in 1980 after making his fortune in pharmaceuticals.

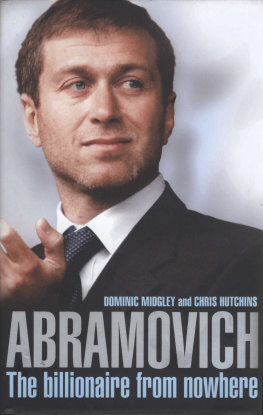

By the turn of the twenty-first century, football was a new game. Millionaire local owners were not enough. Now billionaires and the super-rich were the only individuals with pockets deep enough to bankroll survival and success. The purchase of Chelsea in 2003 by Roman Abramovich, a Russian oligarch who was one of the richest men in the world after building a fortune in the anarchic capitalism of post-USSR Russia, raised the bar. The purchase of Manchester City five years later by Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al Nahyan, a member of the royal family of Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, presented football with its richest family of billionaires.

Crewe survived under the old local-businessman-done-good model, and was a million miles away from the deals made in Abu Dhabi, Doha, Paris and Moscow. At least, it was until today. If there was one thing Harold had never seen at Gresty Road something he thought he might never see it was a full international match, one that brought footballs old world and new into collision. Northern Ireland were about to play a friendly against the Persian Gulf state of Qatar. It is a most unusual one, conceded Harold, a little guarded about the unfamiliar Arab visitors.

The Qatar national team was something of a mystery to everyone at Crewe Alexandra. No one knew when the team would turn up nor who their players were likely to be. The club hadnt heard from a single Qatari fan interested in purchasing a ticket either. Ever since the former president of FIFA Sepp Blatter announced on a stage in Zurich in December 2010 that the tiny, natural-gas-rich state would host the 2022 World Cup finals, Qatar had become something of a pariah in the British press. For the tabloids this frightening new football force from far away in the alien Middle East possessed an ability to punch above its weight almost everywhere except on the football pitch (they had started the year ranked 95th by FIFA, alongside the likes of Liberia and the Faroe Islands) and most football fans in the West were simply incredulous. Qatar was pilloried for investing its extreme wealth in football, and for assembling a national team of mostly naturalised players from other countries their various first XIs during 2018 World Cup qualification saw players appear who had been born in nine different countries. Beneath this lay widespread condemnation for Qatars appalling treatment of the Asian migrant workers building the countrys new infrastructure.

So, in a bid to try to show a different face to the country it regarded as its biggest critic, a mini-tour had been planned for the United Kingdom, kicking off in Crewe against Northern Ireland, before moving, a few days later, north to Scotland for a fixture in Edinburgh. The English FA had welcomed the Qataris with open arms, hosting them at the St Georges Park National Football Centre in Burton-on-Trent about 50 miles away. Somehow, that series of decisions had led to Qatars arrival in Crewe. This is the first time Ive seen Qatar play, admitted Harold, as a few curious middle-aged Northern Ireland fans began filtering in to view the pages of football from a bygone age. And he wasnt happy that the game was being held in a strangely secretive manner. From a personal point of view I am very disappointed that the club hasnt arranged a programme for today, he said. I thought they would have done.

There might not have been a programme, but outside Harolds hut a lone scarf seller was hawking his wares: 136 split scarves, half in the green and white of Northern Ireland, half in the maroon of Qatar. A lot of people go on about the split-scarf thing, said Martin, a Mancunian, but youve got to give people what they want, avent yer? On a normal weekend, Martin a man switched on to the commercial possibilities footballs new gilded elite have brought would be shifting 500 split scarves outside Old Trafford, a position that affords him an informed insight into the increasing numbers of Japanese, Thai, Malaysian and Scandinavian fans that form his customer base. You might never sit next to the same person again inside Old Trafford, he reckoned, but Liverpool hammer United for tourists.

Today he had shifted just 30 scarves, to Northern Irish fans. Ive not seen a single Qatari fan. Just the team, he said, pointing to the huge, blacked-out luxury coach parked outside the grounds front entrance, as if a UFO had just landed. Perhaps Qatars fans had chosen to watch the game from the comforts of The Shard, the luxury, multibillion-pound skyscraper funded almost exclusively by the Qatari state (cost: roughly half a billion pounds) that was now Londons, and Britains, tallest building? Well, Martin replied before leaving to try to offload 106 more green, white and maroon scarves, theyre not likely to come up all the way to Crewe, are they?