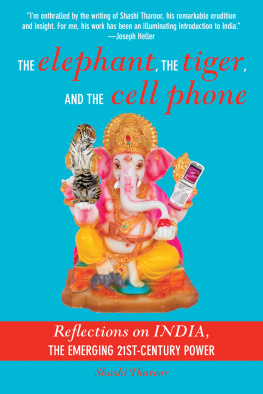

Shashi Tharoor - The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power

Here you can read online Shashi Tharoor - The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, publisher: Arcade Pub, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power

- Author:

- Publisher:Arcade Pub

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Shashi Tharoor: author's other books

Who wrote The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I N A PASSAGE OF HIS MUCH-MISUNDERSTOOD NOVEL The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie writes of the eclectic, hybridized nature of the Indian artistic tradition. Under the Mughals, he says, artists of different faiths and traditions were brought from many parts of India to work on a painting. One hand would paint the mosaic floors, another the human figures, a third the cloudy skies: Individual identity was submerged to create a many-headed, many-brushed Overartist who, literally, was Indian painting.

This evocative image could as well be applied to the very idea of India, itself the product of the same hybrid culture. How, after all, can one approach this land of snow peaks and tropical jungles, with twenty-three major languages and 22,000 distinct dialects (including some spoken by more people than Danish or Norwegian), inhabited in the first years of the twenty-first century by a billion individuals of every ethnic extraction known to humanity? How does one come to terms with a country whose population is 40 percent illiterate but which has educated the world's second-largest pool of trained scientists and engineers, whose teeming cities overflow while two out of three Indians still scratch a living from the soil? What is the clue to understanding a country rife with despair and disrepair, which nonetheless moved a Mughal emperor to declaim, If on earth there be paradise of bliss, it is this, it is this, it is this? How does one gauge a culture that elevated nonviolence to an effective moral principle, but whose freedom was born in blood and whose independence still soaks in it? How does one explain a land where peasant organizations and suspicious officials attempt to close down Kentucky Fried Chicken as a threat to the nation, where a former prime minister bitterly criticizes the sale of Pepsi-Cola in a country where villagers don't have clean drinking water, and yet invents more sophisticated software for U.S. computer manufacturers than any other country in the world? How can one portray an ageless civilization that was the birthplace of four major religions, a dozen different traditions of classical dance, eighty-five political parties, and three hundred ways of cooking the potato?

The short answer is that it can't be doneat least not to everyone's satisfaction. Any truism about India can be immediately contradicted by another truism about India. The country's national motto, emblazoned on its governmental crest, is Satyameva JayatTruth alone triumphs. The question remains, however, whose truth? It is a question to which there are at least a billion answersif the last census hasn't undercounted us again.

For the singular thing about India, as I have written elsewhere, is that you can only speak of it in the plural. There are, in the hackneyed phrase, many Indias. If India were to adopt the well-known U.S. motto, it would have read E Pluribis Pluribum. Everything exists in countless variants. There is no single standard, no fixed stereotype, no one way. This pluralism is acknowledged in the way India arranges its own affairs: all groups, faiths, tastes, and ideologies survive and contend for their place in the sun. The idea of India is that of a land emerging from an ancient civilization, united by a shared history, sustained by pluralist democracy, but containing a world of differences. It is not surprising, then, that the political life of modern India has been rather like traditional Indian music: the broad basic rules are firmly set, but within them one is free to improvise, unshackled by a written score.

When India celebrated the forty-ninth anniversary of its independence from British rule in 1996, our thenprime minister, H. D. Deve Gowda, stood at the ramparts of Delhi's sixteenth-century red fort and delivered the traditional Independence Day address to the nation in Hindi, India's national language. Eight other prime ministers had done exactly the same thing forty-eight times before him, but what was unusual this time was that Deve Gowda, a southerner from the state of Karnataka, spoke to the country in a language of which he did not know a word. Tradition and politics required a speech in Hindi, so he gave onethe words having been written out for him in his native Kannada script, in which they, of course, made no sense.

Such an episode is almost inconceivable elsewhere, but it represents the best of the oddities that help make India India. Only in India could the country be ruled by a man who does not understand its national language; only in India, for that matter, is there a national language that half the population does not understand; and only in India could this particular solution have been found to enable the prime minister to address his people. One of Indian cinema's finest playback singers, the Keralite K. J. Yesudas, sang his way to the top of the Hindi music charts with lyrics in that language written in the Malayalam script for him, but to see the same practice elevated to the prime ministerial address on Independence Day was a startling affirmation of Indian pluralism.

For the simple fact is that we are all minorities in India. There has never been an archetypal Indian to stand alongside the archetypal Englishman or Frenchman. A Hindi-speaking Hindu male from Uttar Pradesh may cherish the illusion that he represents the majority community, an expression much favored by the less industrious of our journalists. But he does not. As a Hindu, he belongs to the faith adhered to by 81 percent of the population. But a majority of the country does not speak Hindi. A majority does not hail from Uttar Pradesh, though you could be forgiven for thinking otherwise when you go there. And, if he were visiting, say, my home state of Kerala, he would be surprised to discover that the majority there is not even male.

Even his Hinduism is no guarantee of his majority-hood, because his caste automatically puts him in a minority. If he is a Brahmin, 90 percent of his fellow Indians are not. If he is a Yadav, a backward caste, 85 percent of his fellow Indians are not. And so on.

If caste and language complicate the notion of Indian identity, ethnicity makes it even more difficult. Most of the time, an Indian's name immediately reveals where he is from or what her mother tongue is: when we introduce ourselves, we are advertising our origins. Despite some intermarriage at the elite levels in our cities, Indians are still largely endogamous, and a Bengali is easily distinguished from a Punjabi. The difference this reflects is often more apparent than the elements of commonality. A Karnataka Brahmin shares his Hindu faith with a Bihari Kurmi, but they share little identity with each other in respect to their dress, customs, appearance, taste, language, or even, these days, their political objectives. At the same time, a Tamil Hindu would feel he has much more in common with a Tamil Christian or a Tamil Muslim than with, say, a Haryanvi Jat, with whom he formally shares the Hindu religion.

What makes India, then, a nation? What is an Indian's identity?

Let me risk the wrath of anti-Congress readers and take an Italian example. No, not that Italian example, but one from 140 years ago. Amid the popular ferment that made an Italian nation out of a congeries of principalities and statelets, the nineteenth-century novelist Massimo Taparelli d'Azeglio memorably wrote, We have created Italy. Now all we need to do is to create Italians. Oddly enough, no Indian nationalist succumbed to the temptation to express the same thoughtWe have created India; now all we need to do is to create Indians.

Such a sentiment would not, in any case, have occurred to the preeminent voice of Indian nationalism, Jawaharlal Nehru, because he believed India and Indians had existed for millennia before he gave words to their longings; he would never have spoken of creating India or Indians, merely of being the agent for the reassertion of what had always existed but had been long suppressed. Nonetheless, the India that was born in 1947 was in a very real sense a new creation: a state that had made fellow citizens of the Ladakhi and the Laccadivian for the first time, that divided Punjabi from Punjabi for the first time, that asked the Kerala peasant to feel allegiance to a Kashmiri Pandit ruling in Delhi, also for the first time. Nehru would not have written of the challenge of creating Indians, but creating Indians was what, in fact, our nationalist movement did.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

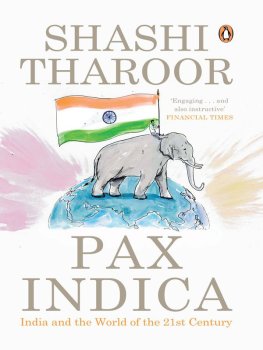

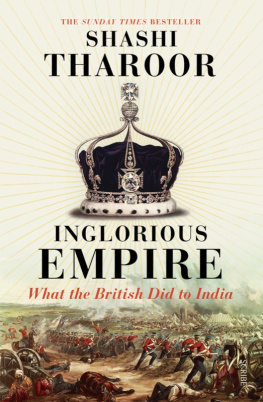

Similar books «The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power»

Look at similar books to The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India, the Emerging 21st-Century Power and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.