Shadows across the Playing Field: 60 Years of India-Pakistan Cricket (with Shahryar Khan)

The Elephant, The Tiger, And the Cell Phone: Reflections on India in the 21st Century

Kerala: Gods Own Country (with M.F. Husain)

Preface

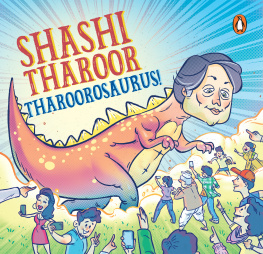

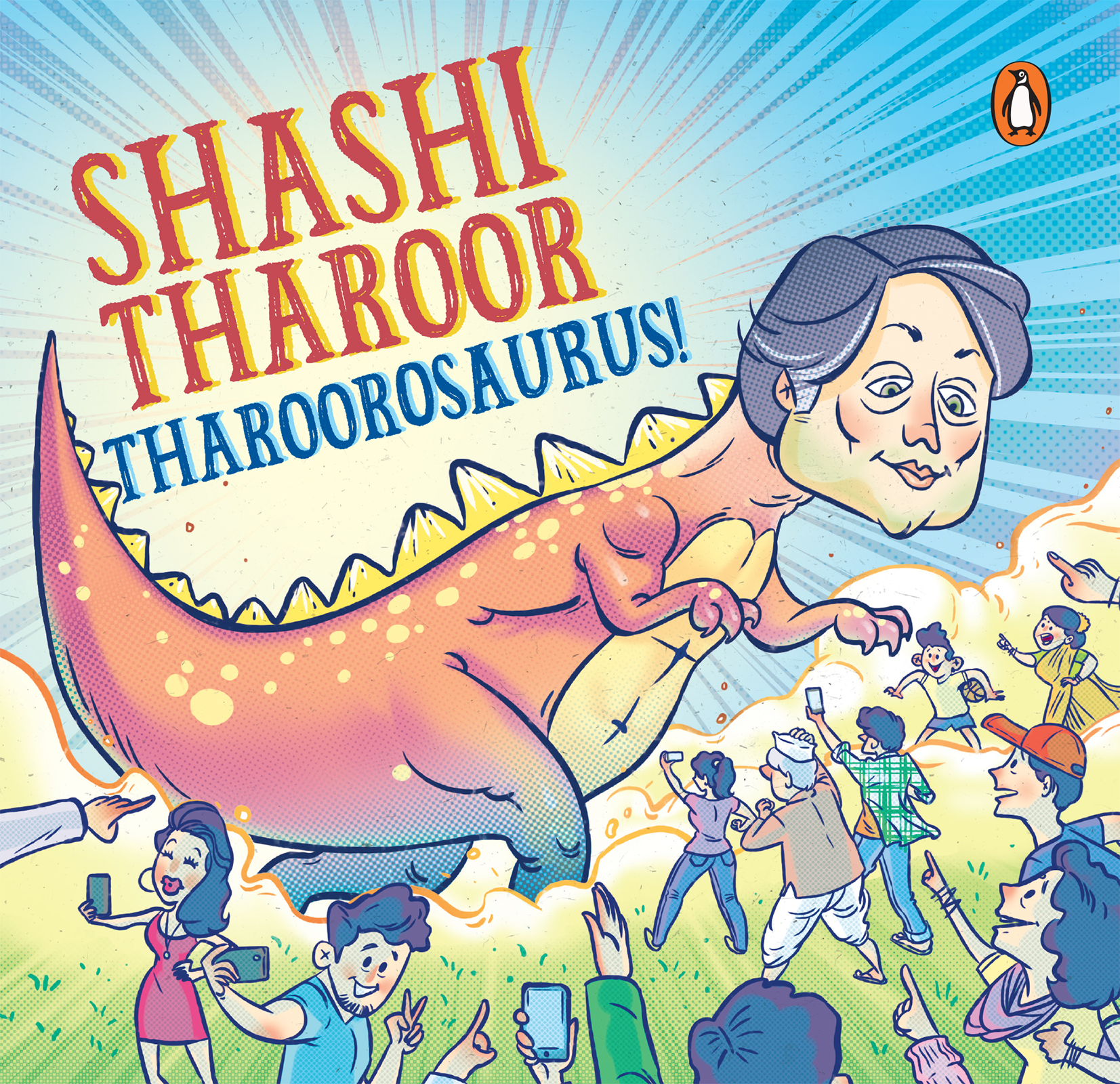

The title Tharoorosaurus was coined by Meru Gokhale, the publisher of Penguin India, who proposed the idea for this book in the rear seat of a taxicab in Jaipur as the two of us were heading to an event of the famed literary festival there. It was her idea of pitching me a book whose title would combine my name with the words tyrannosaurus (since so many are terrified of difficult words) and thesaurus (since people want to be able to look them up).

I laughed it off then, but she persisted, I began to think it might

be fun to do after all, and here is the result.

This is not a scholarly book; I am neither a trained linguist nor philologist, and I have no pretensions to being a qualified English teacher either. It is rather the work of someone who loves words, has loved them all his life, and whose cherished childhood memories revolve around word games with a father who was even more obsessed with them than I am. My father instilled in me the conviction that words are what shape ideas and reflect thought, and the more words you know, the more precisely and effectively are you able to express your thoughts and ideas. In addition, he delighted in the way words could be put together, their origins and the letters of which they were made; there was no word game at which he did not excel, from Scrabble to Bingo to jumbled acrostics in the newspaperand several guess-the-word games of his own devising that kept us busy and distracted on car journeys throughout his life. If Tharoorosaurus imparts to its readers some of the pleasure and delight that words have long afforded me, its purpose will have been amply served.

In 2019, I had begun a Word of the Week column every Sunday in a major newspaper. These began initially as lightly-tossed-off paragraphs, of some 200 words or so, on each word chosen, but as interest grew and readers sought more, I began to take the exercise more seriously, turning out 500800-word columns instead that delved into the etymology of each word and came up with anecdotes about its usage, literary citations and nuggets of history. This book uses the latter format, so that most of the short essays in this book have not appeared anywhere else in this form.

The original idea was to publish fifty pieces in this volume; inspired by my weekly column, I suggested fifty-two, one for each week of the year, in the hope that people would dip into it and keep going back for more. In the end, this volume includes short essays on fifty-three words, since the book is being published in a leap year and we thought we may as well add an extra word for the extra leap day!

A profound word of thanks to Prof. Sheeba Thattil, without whose tireless research, creative thinking and timely assistance, this book would not have been possible. My thanks, too, to the Hindustan Times, for whom I first began to explore many of these words. Though this volume stands by itself, independent of the columns, I am grateful to the Hindustan Times, and in particular Poonam Saxena and Poulomi Banerjee, for setting me off on this journey.

Shashi Tharoor

March 2020

1.

Agathokakological

adjective

CONSISTING OF BOTH GOOD AND EVIL

USAGE

The Mahabharata is unusual among the great epics because its heroes are not perfect idealized figures, but agathokakological human beings with desires and ambitions who are prone to lust, greed and anger and capable of deceit, jealousy and unfairness.

Lets face it, ours is an agathokakological world, and who knows that better than Indians? We live in an era devoid of perfect heroes, where some who are hailed with passionate admiration are despised with equal intensity by others. Nothing around us seems all good or all bad. Indian philosophical systems have always had room for the theory that two opposite poles of good and evil that are considered contradictory can yet coexist naturally in a person, place, or time.

The perfect word to summarize that is agathokakological, which seems to have been coined in the early nineteenth century by sometime British Poet Laureate Robert Southey, best known for his ballad The Inchcape Rock, which tells the story of a fourteenth-century attempt by the Abbot of Aberbrothock to install a warning bell on a sandstone reef called Inchcape (I studied the blessed poem in Mumbai in Class 6, which is when I first heard of Southey). So the word precedes Agatha Christie, whose villainous narrators and seemingly innocent murders are not the inspiration for the term. Southey appears to have combined the Greek roots