PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

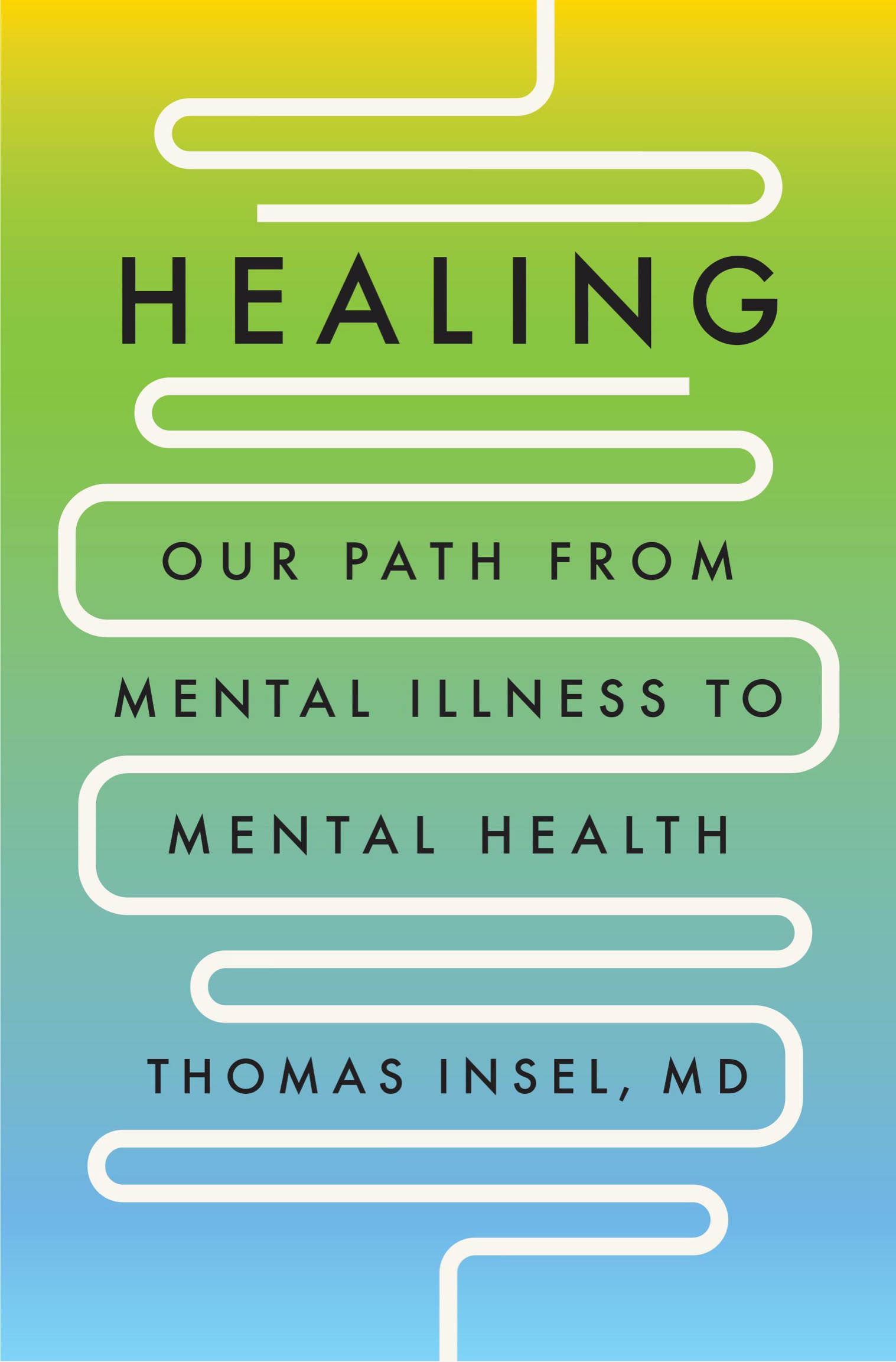

Copyright 2022 by Thomas R. Insel

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Insel, Thomas R., 1951- author.

Title: Healing : our path from mental illness to mental health / Thomas Insel, MD.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2022. |Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021033983 (print) | LCCN 2021033984 (ebook) |ISBN 9780593298046 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593298053 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mental health servicesUnited States. |Mental healthUnited States.

Classification: LCC RA790.6 .I576 2022 (print) | LCC RA790.6 (ebook) |

DDC 362.20973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021033983

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021033984

designed by meighan cavanaugh, adapted for ebook by shayan saalabi

pid_prh_6.0_139201561_c0_r0

For Deb

It was said, in an earlier age, that the mind of a man is a far country which can neither be approached nor explored. But, today, under present conditions of scientific achievement, it will be possible for a nation as rich in human and material resources as ours to make the remote reaches of the mind accessible. The mentally ill and the mentally retarded need no longer be alien to our affections or beyond the help of our communities.

John F. Kennedy, Remarks on signing the Community Mental Health Act, October 31, 1963

A NOTE ON LANGUAGE

Any conversation about mental health has to navigate a linguistic landscape fraught with political, historical, and professional conflicts. Are we dealing with mental illness, mental health, mental health disorders, brain disorders, or behavioral disorders? Are these illnesses, disorders, or conditions? Is the field mental health or behavioral health? And are the people affected patients, clients, consumers, or survivors? Words matter. In this book, I use the term mental illness to refer to disorders of the mind, manifested as changes in how we think, feel, and behave.

I appreciate these disorders originate in the brain, but the term brain disorder connotes an irreversible lesion. Mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders involve a dysregulation of brain activity, perhaps a disorder of connectivity or a brain arrhythmia, but not (yet) an identifiable lesion. And relative to some neurodegenerative disorders, people can recover from mental disorders. On the other hand, brain disorder accurately conveys the serious nature of the problem. There is a risk that the term mental disorder means a mild or moderate condition that is neither deadly nor disabling.

Behavioral disorders include addictions, from nicotine to opiates. Substance use and abuse is frequently associated with mental illness, but for this book will be treated as a consequence and not a core form of mental illness. I avoid the terms behavioral health and behavioral disorder when talking about serious mental illness because these disorders involve much more than behavior, but I recognize that for health systems and payers, behavioral health describes the broad area of mental illness, addiction, and sometimes wellness.

The term mental health disorder is one I particularly dislike. We speak of heart diseases, not heart health disorders, or metabolic diseases, not metabolic health disorders. I see no reason to treat mental illnesses differently.

Are these disorders, illnesses, or conditions? I will use the terms disorder and illness interchangeably. In either case, we do well to remember that the labels we use are simply conventions with limitations. Labels like illness or disorder describe a set of symptoms. They do not define a person.

And I refer to people with these illnesses as patients. Psychotherapists use the term client and health systems refer to consumers. People with lived experience sometimes call themselves survivors. My approach is unapologetically medical, not because I believe in a paternalistic medical model for treatment (I dont) and not because I think that medication is the only treatment for mental illness (I dont), but for two practical reasons: first, I want public and private health insurance to pay for the treatments that work, and second, I want the standards we expect for medical and surgical care to apply to the treatment of mental illness. You cant demand parity for clients who are not patients. If we want the benefits and rigor of medical science, our language needs to adhere to medical and scientific conventions. But as you will see, a medical approach introduces a mountain range of constraints that we will need to cross if we want a different future for people with mental illness.

Finally, a note about names. Individuals identified with only a first name in the text are aggregates of many individuals and a complete description of no one. These are fictional, in the sense that none of these people exist, but specific characteristics are derived from real people with details changed to protect anonymity. These case histories were constructed to be representative. They may therefore seem familiar to people I have known and to millions I have not known. But these case histories are not portrayals of any individual, and any resemblance to a person living or dead is both unintended and unavoidable. By contrast, individuals identified with first and last names are real, and those interviewed and quoted have reviewed the contents for accuracy.

INTRODUCTION

I have wrestled with mental illness as a parent, a scientist, and a doctor for nearly half a century. Trained as a psychiatrist and working as a neuroscientist, Ive spent the last four decades witnessing research breakthroughs on how the brain works in both health and disease. Ultimately, I became, for more than a decade, the nations psychiatrist, director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), overseeing more than $20 billion for mental health research. I helped President George W. Bush respond to school shootings and co-led President Barack Obamas Brain Initiative. I advised members of Congress on mental health care and worked with leaders in the Pentagon on suicide in the military. In short, it was my job to make a difference for Americans with mental illness. I should have been able to help us bend the curves for death and disability. But I didnt. Because I misunderstood the problem. Or maybe its more accurate to say that the problem I was solving by supporting brilliant scientists and dedicated clinicians was not the problem that faced nearly f ifteen million Americans living with serious mental illness.

On a cool May evening in 2015, during my last year as director of the NIMH, I was in Portland, Oregon, giving a presentation to a roomful of mental health advocates, mostly family members of young people with a serious mental illness. NIMH is the worlds largest funder of research on mental illness, supporting studies of the causes and treatments of disorders like depression and schizophrenia, as well as basic research on how the brain works. Since the NIMH is funded by taxpayers, interacting with the public was an important part of my job. That day, I clicked through my standard PowerPoint deck that featured our recent progress: high-resolution scans showing brain changes in people with depression, stem cells from children with schizophrenia showing abnormal branching of neurons, and epigenetic changes as markers of stress in laboratory miceall of the evidence of our scientific success and reasons for citizens to be thankful for such wise stewardship of their taxpayer dollars. We had learned so much! We were making so much progress!