Contents

Page List

Guide

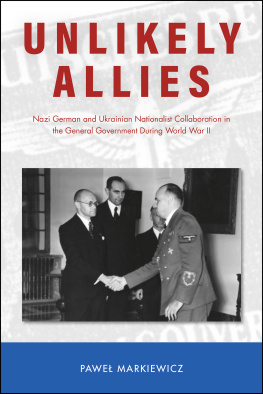

UNLIKELY ALLIES

Central European Studies

Charles W. Ingrao, founding editor

Paul Hanebrink, editor

Maureen Healy, editor

Howard Louthan, editor

Dominique Reill, editor

Daniel L. Unowsky, editor

Nancy M. Wingfield, editor

The demise of the Communist Bloc a quarter century ago exposed the need for greater understanding of the broad stretch of Europe that lies between Germany and Russia. For four decades the Purdue University Press series in Central European Studies has enriched our knowledge of the region by producing scholarly monographs, advanced surveys, and select collections of the highest quality. Since its founding, the series has been the only English-language series devoted primarily to the lands and peoples of the Habsburg Empire, its successor states, and those areas lying along its immediate periphery. Among its broad range of international scholars are several authors whose engagement in public policy reflects the pressing challenges that confront the successor states. Indeed, salient issues such as democratization, censorship, competing national narratives, and the aspirations and treatment of national minorities bear evidence to the continuity between the regions past and present.

Other titles in this series:

Balkan Legacies: The Long Shadow of Conflict and Ideological Experiment in Southeastern Europe

Balzs Apor and John Paul Newman (Eds.)

On Many Routes: Internal, European, and Transatlantic Migration in the Late Habsburg Empire

Annemarie Steidl

Teaching the Empire: Education and State Loyalty in Late Habsburg Austria

Scott O. Moore

Croatian Radical Separatism and Diaspora Terrorism During the Cold War

Mate Nikola Toki

Jan Hus: The Life and Death of a Preacher

Pavel Soukup

UNLIKELY ALLIES

Nazi German and Ukrainian Nationalist Collaboration in the General Government During World War II

PAWE MARKIEWICZ

Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana

Copyright 2021 by Purdue University. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available at the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-61249-679-5 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-61249-680-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-61249-681-8 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-61249-682-5 (epdf)

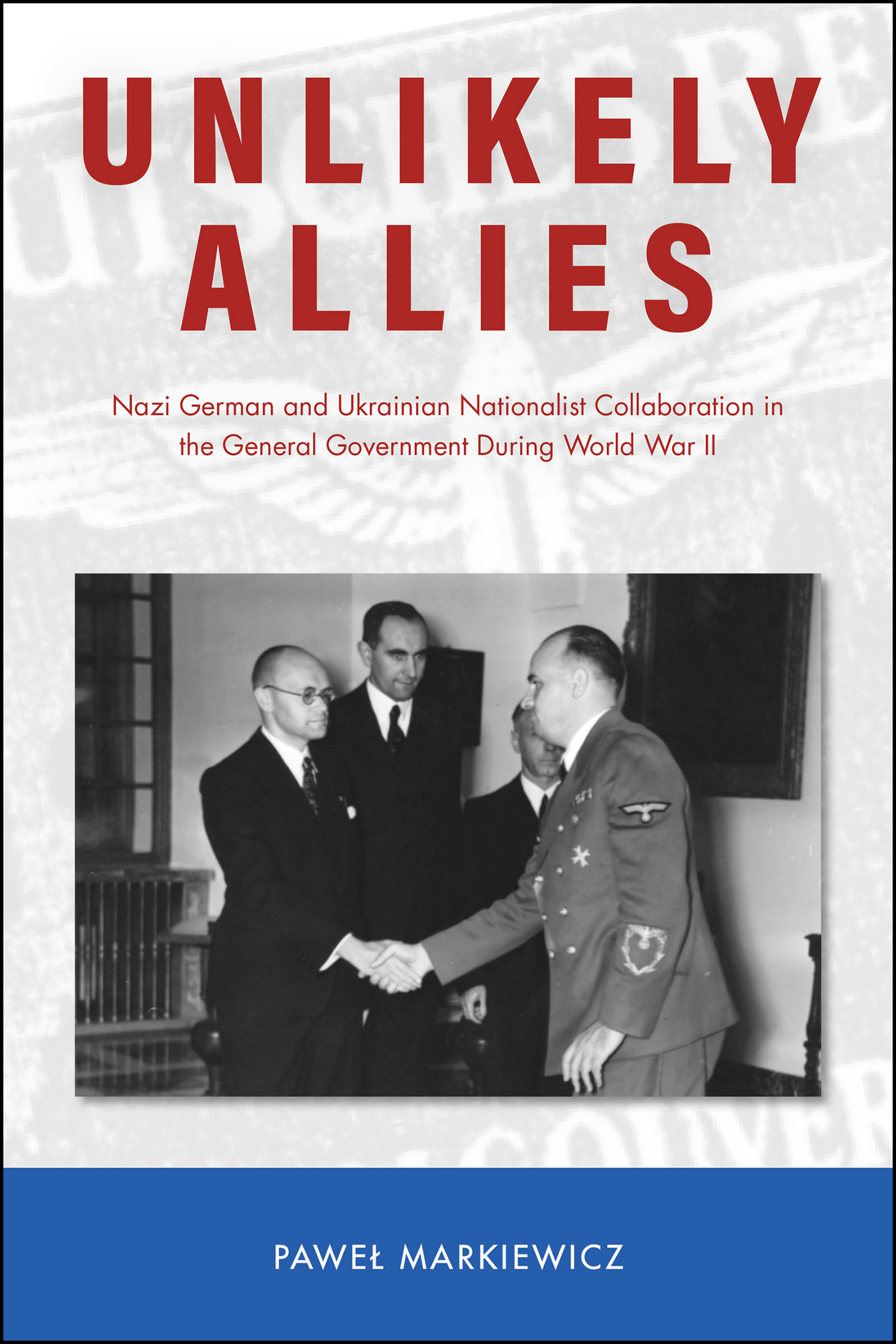

Cover image: Hans Frank and Volodymyr Kubiiovych (National Digital Archive, Poland)

For those who supported this journey and those that questioned it

CONTENTS

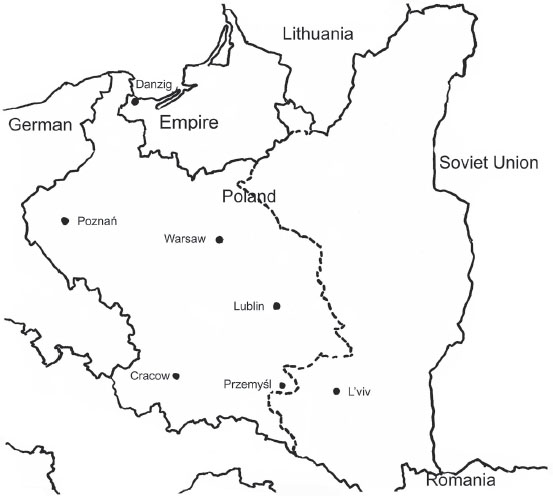

Poland 19191939

Interwar Poland, 19191939. (Courtesy of Christoph Mick)

------- German-Soviet demarcation line after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, 23 August 1939

Poland after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Poland after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. (Courtesy of Christoph Mick)

------ Borders 1938

Administrative borders under German occupation

German administrative borders after the attack on the Soviet Union

German occupation zones created from interwar Polish territory. (Courtesy of Christoph Mick)

PREFACE

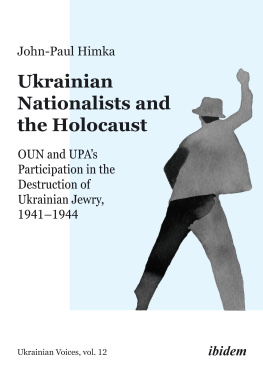

J ANUARY 1944. WORLD WAR II was entering what would be its final bloody stages. In the east a Soviet Red Army offensive was pushing the German Wehrmacht back west while Allied leaders were considering where and when to invade the European continent for the final assault against the Nazis. A Ukrainian weekly newsreel for that year, however, projected a different image of the war. As part of a ceremony to ring in that pivotal year in what the Germans then called Lemberg (what was previously Lww and is currently Lviv), Volodymyr Kubiiovych, head of the Ukrainian Central Committee, visited Governor Otto Wchter, the Nazi administrator of the Galicia district of the General Governmentthe German occupation zone carved out from part of the Second Polish Republic. Of course, this was not the first time that the erudite Kubiiovych led delegations to high-ranking German officials. Since 1940 he regularly met with Nazi officials, including General Governor Hans Frank, either informally or formally to also ring in the New Year as well as on the anniversaries of Hitlers birthday in April and the General Governments creation in October. During each meeting, Kubiiovych emphasized what he believed was a developing relationship between Ukrainian nationalists and the occupation regime. Wearing a double-breasted suit and greeting Wchter that January as he so often did with the other administratorsby raising and outstretching his right arm in the Nazi fascist stylethis time the tall, slim, bald, bespectacled Kubiiovych expressed his concern over the Red Armys advance toward the General Governments borders. He pledged that the recently formed 14th Waffen SS Division Galizien consisting of young Ukrainian recruits from throughout Wchters district would defend the lands alongside the Wehrmacht, thereby destroying their common enemy. For Kubiiovych, who played a prominent role in urging the young men to volunteer for armed service, the division was a piece of personal pride. He reveled in the notion of contributing a Ukrainian unit under German command to the anti-Soviet struggle. As was customary, upon exchanging pleasantries and before leaving, Wchter was presented with a special gifta large figure of a bearded St. Nicholas holding fir branches; an act that elicited smiles from both Kubiiovych and the governor.

Fast-forward seventy-six years to 2020. On January 14 Ukraines Verkhovna Rada or parliament passed a resolution outlining events and individuals the country would commemorate throughout the year. Among those chosen was the late Volodymyr Kubiiovych. The text of the resolution explaining why he was selected to be honored on March 23 reads: 120 years since the birth of Volodymyr Kubiiovych (19001985), intellectual, historian, geographer, encyclopedist, public and political activist, organizer and editor-in-chief of the Entsyklopediia Ukranoznavstva. Twenty years earlier the Ukrainian postal service issued a specially designed envelope on the 100th anniversary of Kubiiovychs birth, complete with sketches of him, his encyclopedia, and his geographic atlas. Some might argue that the brief description invoked in the parliamentary resolution rather conveniently summarized who he was. However, just as for so many born and living in Poland during part of their lifetime, one question immediately comes to mindhow did Volodymyr Kubiiovych experience World War II? Some would say that how he lived through the war was inconsequential. He survived. That is what counted. It isnt surprising that Kubiiovychs wartime experience is omitted or overlooked as only a fraction of it is known today. Besides, what is known either stems from memoirs or encyclopedia entries written by him or from historical monographs that mentioned him in passing while discussing broader Polish-Ukrainian or German-Ukrainian topics of the period.

The lack of a convincing answer to this question motivated me to find one. After years of research, my answer is presented in the following pages. It adds what I believe is a valuable missing piece to the above description and overall image of who Volodymyr Kubiiovych was before questioning whether he is truly deserving of being recognized and honored by a country of which he was never a citizen; rather, he recognized himself as an ethnic element of the people inhabiting its ethnographic territory. I first heard of Volodymyr Kubiiovych in 2012 upon beginning my doctoral studies at the renowned Jagiellonian University in Krakw, Poland. It was during six years of research that I came to familiarize myself with Kubiiovychs World War II face. That is when this book began. Although at first glance it may appear so, this is not a biography of Volodymyr Kubiiovych. Rather, it is an analysis of German-Ukrainian relations during the Second World War in which Kubiiovych plays a prominent role. Three features constitute this relationship. The first is Volodymyr Kubiiovych, who headed the Ukrainian Central Committee (UTsK), formally a welfare organization that was in fact the quasi-official center of nationalist political life under German occupation. It was in that capacity that Kubiiovych represented occupied Ukrainians before General Governor Hans Frank and his administrators. To be clear, he was no Jozef Tiso, the priest turned politician who headed the German client Slovak Republic during World War II. Rather, Kubiiovych was a war professor, one of the many intellectuals involved on the side of a belligerent in the war for lost souls or the need to clearly define and differentiate a community of people from an alien or enemy community. The second component is Nazi German policy toward non-Germans in the General Government, something that rather successfully divided occupied society throughout the war and bestowed on Ukrainians some preferential social treatment. The last element is the cooperation between Kubiiovych and the UTsK, on the one hand, with the German occupation regime, on the other.