Contents

Guide

Page List

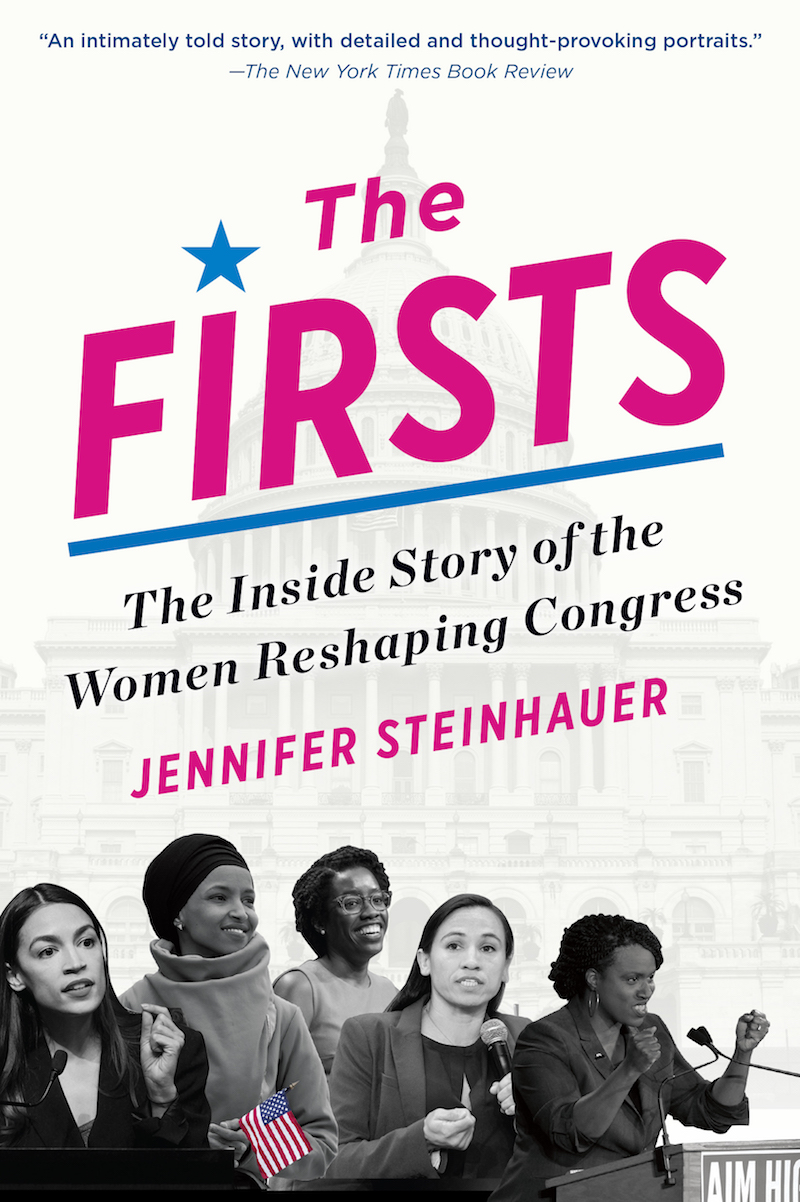

The

Firsts

The Inside Story of the Women Reshaping Congress

Jennifer Steinhauer

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2021

Published by

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

WORKMAN PUBLISHING

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

2020 by Jennifer Steinhauer. All rights reserved. First paperback edition, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, January 2021.Originally published in hardcover by Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill inMarch 2020.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data for this title is available from the Library of Congress.

e-ISBN: 978-1-64375-021-7

To all the women who have dared to run for Congress, especially those who were told they could not.

Contents

Introduction

The New Arrivals

Yeah, we have to fix this shit.

Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA)

On most days of the year, tourists stream through the National Statuary Hall, a resplendent room in the center of the US Capitol in Washington, DC. Here, prominent American men, from Sam Houston to Thomas Edison, are celebrated with giant effigies, surrounded by colossal marble columns and ornate drapes. On the first Thursday of 2019, however, the august chamber felt like the bustling arrivals terminal at John F. Kennedy International Airport.

New members of Congress, sworn in just an hour earlier, mingled with their excited families as they waited to have their photos taken in a chaotic mass of ill-formed lines controlled by barking security officers who could not yet recognize a single one of them. The most diverse Congress in history was on full display. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, her head covered in a festive orange scarf, clutched a string of pale prayer beads in one hand, her son Adnans hand wrapped in the other. An entire family dressed in traditional Laguna Pueblo garb traipsed through toward the Capitol Rotunda, trying to keep up with Deb Haaland of New Mexico. Abigail Spanberger of Virginia, a former CIA operative, stood with her three daughters, who were dressed in identical blue-and-gold-flecked fancy frocks, the same ones the girls wore the night their mother defeated a Republican Tea Party incumbent after a brutal race. Small children in velvet dresses with itchy crinolines, overly large suits, or African-print pants clung to parents. Exhausted, at least one curled up on the floor by a statue of Brigham Young.

Rashida Tlaib of Michigan, in a cranberry-colored thobe, the native dress of Palestine, pushed a wheelchair carrying her mother, who fretted in Arabic about the jacket she had left back in Tlaibs new office. Its an office, Mom. Nothing is going to happen to it! Tlaib said. As they made their way through the Capitol, Iowas senators, Republicans Chuck Grassley and Joni Ernst, swept by. Who is that? Tlaibs mother asked. Her daughter, a brand-new representative, shrugged. She had no idea.

Just shy of a century after women were granted the right to vote, the 116th Congress boasts the greatest number of female members ever: 106 women in the House of Representatives and 25 in the Senate, a milestone at once momentous and paltry. Democrats were ebullient, having retaken the House after eight years in the minority, picking up forty new seats, a bit more than 60 percent of them filled by women. In all, thirty-five new women joined Congress in 2019including two who won in special electionsand all but one was a Democrat. Beyond gender, 22 percent of the House and Senate in 2019 were members of racial or ethnic minorities, a percentage that has steadily increased over the last decade. The new House class tilted younger and less wealthy, too.

This younger, more diverse, and more female legislative branch would become immediately consequential. The members would alter the way that representatives and senators communicate with each other and the outside world, and how policy debates would be framed. So long a hermitage from the social and economic upheavals in American life, Congress would soon become their fulcrum, with racial, ethnic, class, and generational conflicts a central narrative. Deep divisions over the direction and future of the Democratic Party would surface between the new generation of progressives, eager to push the party to the left, and centrists, who thought moderation was the key not only to the partys survival, but also to getting rid of Republican president Donald Trump.

Two women in particular, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), at twenty-nine the youngest woman ever to serve, and Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-MN), one of the first Muslim women ever elected, would in short order dominate the national political discourse, unheard of for freshman lawmakers in general and women in particular, who historically had not arrived in Washington, DC, armed with self-assurance, outspoken views, and millions of followers. The new women would upend conventional political and legislative conversations and challenge notions of comity in a body where duplicity and spuriousness had long been concealed by quaint rules governing acceptable speech. They would face off with their colleagues and their leader, Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), the first woman to be Speaker of the House and one of only seven Speakers to hold the gavel in nonconsecutive terms. Within months of taking their seats, the freshmen would spar directly with the president himself, who would attempt to use the women as tools to demonize the newly empowered Democrats as politically dangerous and to starkly cleave the nation over questions of race and belonging. In short, the story of the Firsts, while still being written, would mark a historical turning point both for Congress and for American women.

This day of elation for Democrats also represented a tumultuous new beginning for many men in Congress, who had just spent the last year in a state of thinly disguised terror as House women led a movement to change the process for handling sexual harassment claims on Capitol Hill. On the one hand, some of the more liberal men were careful to wax on about how thrilled they were to have these exciting new women in Congress. But several months later, even they would let it be known to House leadership that they were sick of hearing about them. The men wanted us to know they were still in charge, one senior female Democrat, unamused, told me some months later.

And before this historic day was over, the freshmen had made it clear they were a new voice in town. Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-MI) startled her colleaguesand stepped on Pelosis message of a restrained and temperate new Houseby announcing to supporters that she was going to impeach the motherfucker, foreshadowing the protracted debate among Democrats over how to handle President Trump, which would eventually result in an impeachment showdown.

The new members arriving on Capitol Hill in January of 2019 found themselves in the oddest of work spaces. On most Wednesdays when Congress is in session, tourists parade through the Rotunda, their necks craned toward its spectacularly domed ceiling. Groups who have convened for lobbying fly-in days cram the hallways and cafeterias of House and Senate office buildingsone day, its the vision-impaired, tapping canes along the floor; another, it is medical students in white jackets, mainlining Dunkin Donuts. Sometimes, its presidents of childrens museums; another time, its dairy lobbyists toting ice cream. I recently saw a group in medieval garb; I have yet to unpack that one. Occasionally, a dog will scamper down a hallway, escaping its human, perhaps a member (or more likely an aide) preparing to take it for a walk.