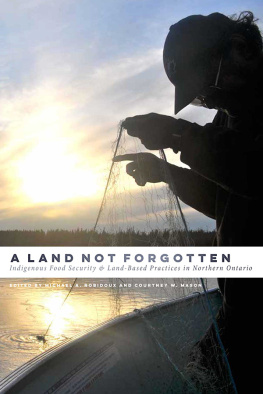

A LAND NOT FORGOTTEN

Indigenous Food Security & Land-Based Practices in Northern Ontario

EDITED BY MICHAEL A. ROBIDOUX

AND COURTNEY W. MASON

The Authors 2017

21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Treaty 1 Territory

uofmpress.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-0-88755-757-6 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-88755-517-6 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-88755-515-2 (epub)

Cover and interior design by Jess Koroscil

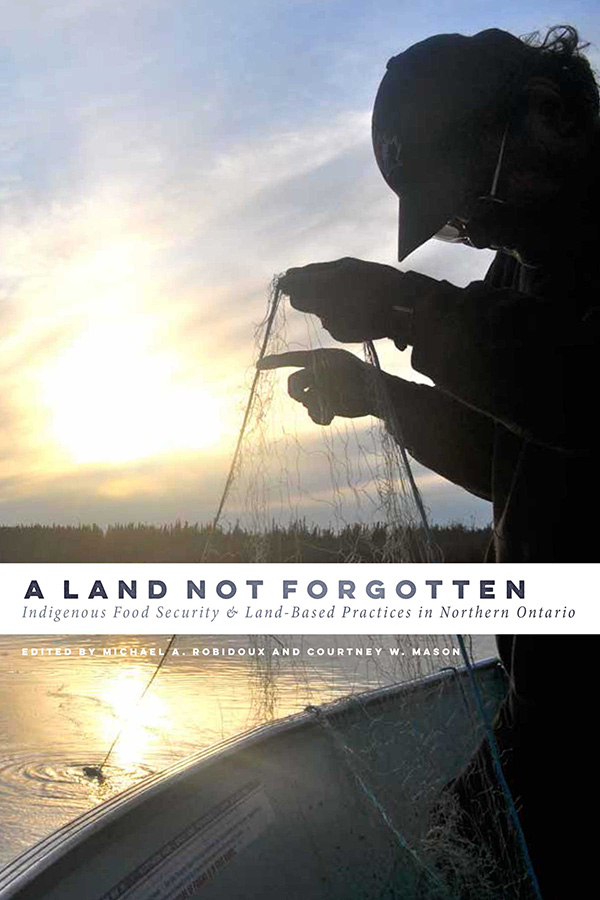

Cover image: Simeon Cutfeet, an Oji-Cree community member who lives in Wapekeka, northwestern Ontario. Photograph by Courtney W. Mason.

Printed in Canada

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This collection would not have been possible without the strong partnerships that were formed over the many years of working with First Nations communities and organizations in Northwestern Ontario. These partnerships were originally fostered with the assistance of Margaret Kenequanash, the executive director of the Shibogama Tribal Council, to whom we are extremely grateful. We are deeply indebted to the leadership at the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) who originally partnered with the Indigenous Health Research Group (IHRG) in 2006, and have continued to support our work ever since. In particular, we would like to thank Wendy Trylinski at NAN for her continued involvement in IHRG research activities and for facilitating relationships with NAN communities.

There are so many people to thank at the community level, starting with the chiefs and band councils from the Kasabonika Lake First Nation, Wapekeka First Nation, and Wawakapewin First Nation. In each of the communities there are hunters, food preparers, and food champions who were instrumental in all aspects of our community involvement. This not only meant working with researchers to achieve project goals, but taking us into their homes, sharing food, sharing knowledge, sharing culture, sharing time, taking care of our students, and generally providing life-changing experiences for all of us. We are forever grateful to Clara Winnepetonga, Derek Winnepetonga, Chris Anderson, Jonas Beardy, Laura Semple, Irene Semple, Keith Mason, Leon Beardy, Cathy Pemmican, Simon Frogg, Arlene Jung, Archie Meekis, Rhoda Meekis, and Leighton Anderson.

We would also like to thank the many research coordinators and research assistants, whose work was critical throughout the various stages of research for this project and in the manuscript preparation. Thank you to Shinjini Pilon and Corliss Bean for their patience and perseverance in managing IHRG research activities and all of the partnerships that came along with the research. Thanks to our wonderful students who lived and worked in communities throughout the project, Michelle Kehoe, Melanie St-Jean, Meagan Ann Gordan, Rebecca Brodmann, Desire Streit, Cindy Gaudet, Michael Padraig Leibovitch Randazzo, and Erin OReilly. We would also like to thank Caroline Anna Head for her assistance formatting the manuscript.

We are grateful to the editorial staff at the University of Manitoba Press, who have been extremely patient with us as we put this book together. In particular, we would like to thank Glenn Bergen, who first approached us about this book project; Jill McConkey, who was great throughout the whole process; and Barbara Romanik for her diligent and thoughtful editing. We, along with Simon Froggs family, are indebted to Glenn and Jill for arranging for a preliminary version of the book to be sent to Simon just days before his passing. It meant so much to Simon to see his words in print. Thank you.

As always, we need to acknowledge our families for their ongoing support. Sharon, Sarah, and Hannah, thanks for looking out for one another while Michael was away. Courtney wishes to thank Josephine, his parents, and his family for the many ways that they support his work.

This book was made possible by a financial contribution from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and Health Canada, through the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer.

MICHAEL A. ROBIDOUX, JOSEPH LEBLANC, AND COURTNEY W. MASON

Prologue

CONVERSATIONS WITH WAWAKAPEWIN ELDER SIMON FROGG

Over the last decade, through our community-based research, we have had the great honour of working closely with Oji-Cree Elder Simon Frogg. Our relationship with Simon has significantly informed our understandings of the connections between food, the well-being of people, and the environment. In sharing with us his experiences and traditional teachings, Simon has helped us to see the connections between our work and Indigenous ways of knowing. In Oji-Cree culture, there is virtually a story for every type of food. These stories, often told with a humorous tone, contain directions for respectful interactions with other living beings as well as cautionary warnings for breaching our responsibilities to one another. At Simons request we share with you the story of Wesakechak and the Geese.

Simon Frogg: You ask me where we need to start this book project? Well, when we started to work with the University of Ottawa, I said if were going to be talking about food and how its supposed to help the well-being of our people, I have to know where this is basedif there is any connection to our way of understanding. Thats what Im interested in and how we arrived at that connection. What I have come to realize is that the perspective of our people, or what we believe, can be found in the teachings that have been handed down, primarily through what are fostered in the legends. For me thats always a good starting point. For instance, when I have to deal with some type of process or program or whatever, the first thing I do is try to figure out where it exists in our teachings, in the legends. That is the first thing I try to do. I try to find if there is some type of original direction relating to whatever Im doing. It starts with the historical aspects of traditional foods and how they are gathered. We have a long history shaping how we understand these things, which have been made known to us through the legends and stories associated with them. So my suggestion is that we include portions of those in the book, stories that tell this history, the knowledge of our traditions, and our teachings around wild foods. The securing, preparing, and storing of wild foodthere are characters in the legends that give us knowledge and teachings that go far back in time. Its not something we just pulled out of a hat. Its something that our people understood through teaching stories and legends, which have been handed down to us. Theres so many of them. Theres virtually a story for every food source. Of course there is a component of humour, but they are made up of different characters, characters from a divine period when there were only animals. Do you remember the Wesakechak story? Thats also a prophecy, do you remember?