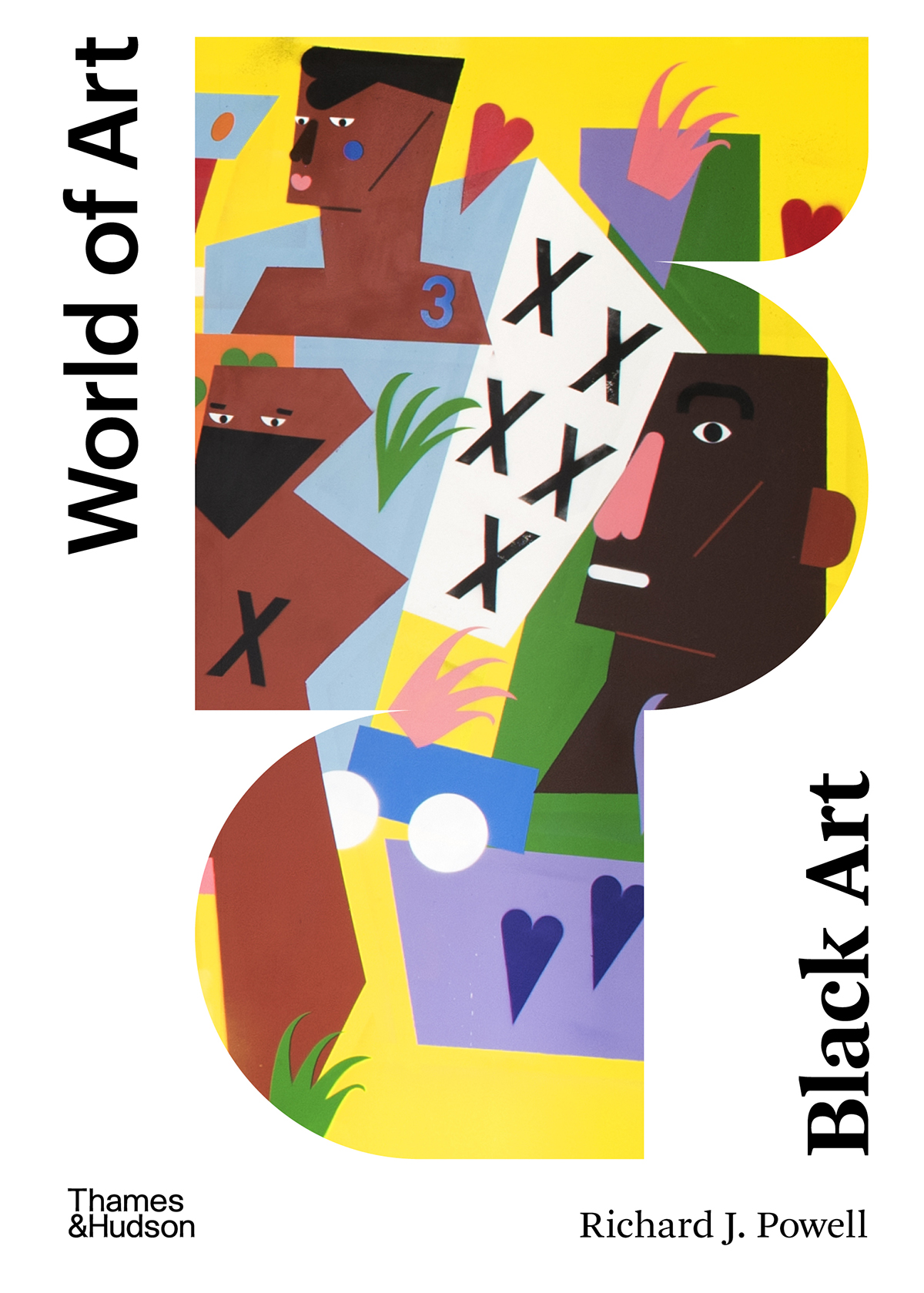

Sylvia Snowden, Mamie Harrington, 1985

About the Author

Richard J. Powell is the John Spencer Bassett Professor of Art and Art History at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, where he has taught since 1989. He studied at Morehouse College and Howard University, before gaining his doctorate in African American art history at Yale University. In addition to teaching courses in American art, the arts of the African Diaspora, and contemporary visual studies, he has written on topics ranging from primitivism to postmodernism, and has helped organize several exhibitions, including Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance for Londons Hayward Gallery in 1997; To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities for the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Addison Gallery of American Art in 1999; and Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist for the Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University in 2014. His publications include: The Blues Aesthetic: Black Culture and Modernism; Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture; Going There: Black Visual Satire; and Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson. From 2007 until 2010, Powell was Editor-in-Chief of The Art Bulletin.

Contents

Acknowledgments

In addition to the institutional support and the many people who helped me realize the original 1997 edition of this book, I thank Duke Universitys John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute. This revised edition has benefited greatly from the intellectual exchange that was generated among my colleagues in the From Slavery to Freedom humanities labs, held at Dukes Franklin Humanities Institute, beginning during the academic year of 201819. For the time and research assistance to study and revise, I am eternally grateful.

The Alchemy of Black

In 1952, the Martiniquan psychiatrist and cultural theorist Frantz Fanon wrote Peau noire, masques blancs (Black Skin, White Masks): a provocative book that, in its analysis of the damaging psychological effects that racism had on peoples of African descent, shattered the more conciliatory views of race relations that were proffered by social and political apologists during this period. In the section of the book that challenged French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartres proposal that the black artists declaration of cultural difference be eventually subsumed by a future universalism and existential attitude, whose dominion meant cultural assimilation, Fanon responded with the following autobiographical disclaimer and riddle:

The dialectic that brings necessity into the foundation of my freedom drives me out of myself. It shatters my unreflected position. Still in terms of consciousness, black consciousness is immanent in its own eyes. I am not the potentiality of something. I am wholly what I am. I do not have to look for the universal. No probability has any place inside me. My Negro consciousness does not hold itself out as a lack. It is. It is its own follower.

Similarly, the late seventeenth-century slave drum, acquired in colonial Virginia by the physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane, raises a racial conundrum for students of black diasporal arts and cultural studies.[] With its stretched and pegged membrane, indented base, and rotund wooden body covered with decorative blocks and striations, this drum looks very much like percussive instruments found among Akan- and Fon-speaking peoples in West Africa. But even with this resemblance, as well as its African wood (cordia africana), and the likelihood that the people who made it retained Akan or Fon design sensibilities, its new context and possibly new use in colonial Virginia removed it from its Old World frame of reference.

Slave drum, late seventeenth century

Sloane acquired the drum in the early eighteenth century, at the height of Virginias involvement in the mass importation of enslaved Africans; his collection ultimately formed the nucleus of the British Museum in London, where the drum is still housed. The drums specific Akan or Fon ritual identity has therefore been replaced with an identity that is African in kind, American in provenance, interpreted as an artifact through the lens of the Enlightenment, and founded on all the social, political, and cultural austerities of slavery. What students have had to struggle with is the fact that the American-in-origin, African-in-design, and transatlantic-in-praxis lineages of this drum are perhaps more easily understood in the context of an African diasporal experience which, in practical terms, can be summed up by the all-encompassing, historical designation black.

The intensity, irreducibility, and emphatic nature of the word black obviously contradict this drums complex history and hybrid nature. Yet, following the irreversible impact of the transatlantic slave trade, the English Black, the French Noir, and the Spanish, Portuguese, and eventually Anglo-American Negro became terms that differentiated a largely New World phenomenon of African diasporal cultures and peoples from their ethnic-specific ancestors and relatives. Of course, the Europeans who were engaged in the slave trade had long referred to Africans as blacks (in addition to other, frequently disparaging designations), but over time and with a more entrenched colonial foothold in the Americas, ethnic terminologies like Angolan, Calabar, Nago, and Coromantee (used for the first and second generations of African-born slaves) were superseded by the short and stinging black: a term that, in its brusque utterance, contained a white supremacist sense of racial difference, personal contempt, and, oddly enough, complexity that came to define these new African peoples.

Conventional wisdom during and after slavery would have separated the perceived singularity of being black from the inherent multiplicity of being racially mixed, yet these polarities collapsed under their own short-sighted logic and inflexible nomenclature. Given the range of complexions and body types among African peoples, black (in spite of its stark, verbal fixity) has always signified morevisually and conceptuallythan it has been allowed to represent officially. Sloane and other thinkers of the Enlightenment were often surprised by the variety of physical characteristics that they observed among New World Negroes. They were certainly aware that this variation from partially African in appearance to almost entirely Caucasian-looking was due to the rape and concubinage of female slaves by white masters and male overseers, but they deluded themselves in classifying these mixed and enslaved entities as black.

During the colonial period there were other more specific terms for perceived racial and/or cultural mixtures. Apart from the commonly and often loosely used Creole, Mulatto, Quadroon, and Octoroon, the Spanish-speaking lite of colonial Mexico invented at least fifty-three different names for various racial intermixtures.[] In an anonymous Mexican painting of the castes from the last quarter of the eighteenth century, sixteen of these race/class categories are illustrated with, surprisingly, those of a perceived African ancestry not always confined to the lowest social rungs. What this caste fluidity suggested was that, rather than ones pigmentation or phenotype, proximity to the ruling majoritys cultural norms in dress, occupation, and wealth was more important in determining status and class. Among the sixteen categories in this painting, an identifiable, New World Africanitya result of the transatlantic slave trade, colonialism, and miscegenationvaunted its hybridity and cultural defiance in a litany of imaginative, Spanish-derived labels, such as

Next page