LIFE

STORIES

~ OF THE ~

NICARAGUAN

REVOLUTION

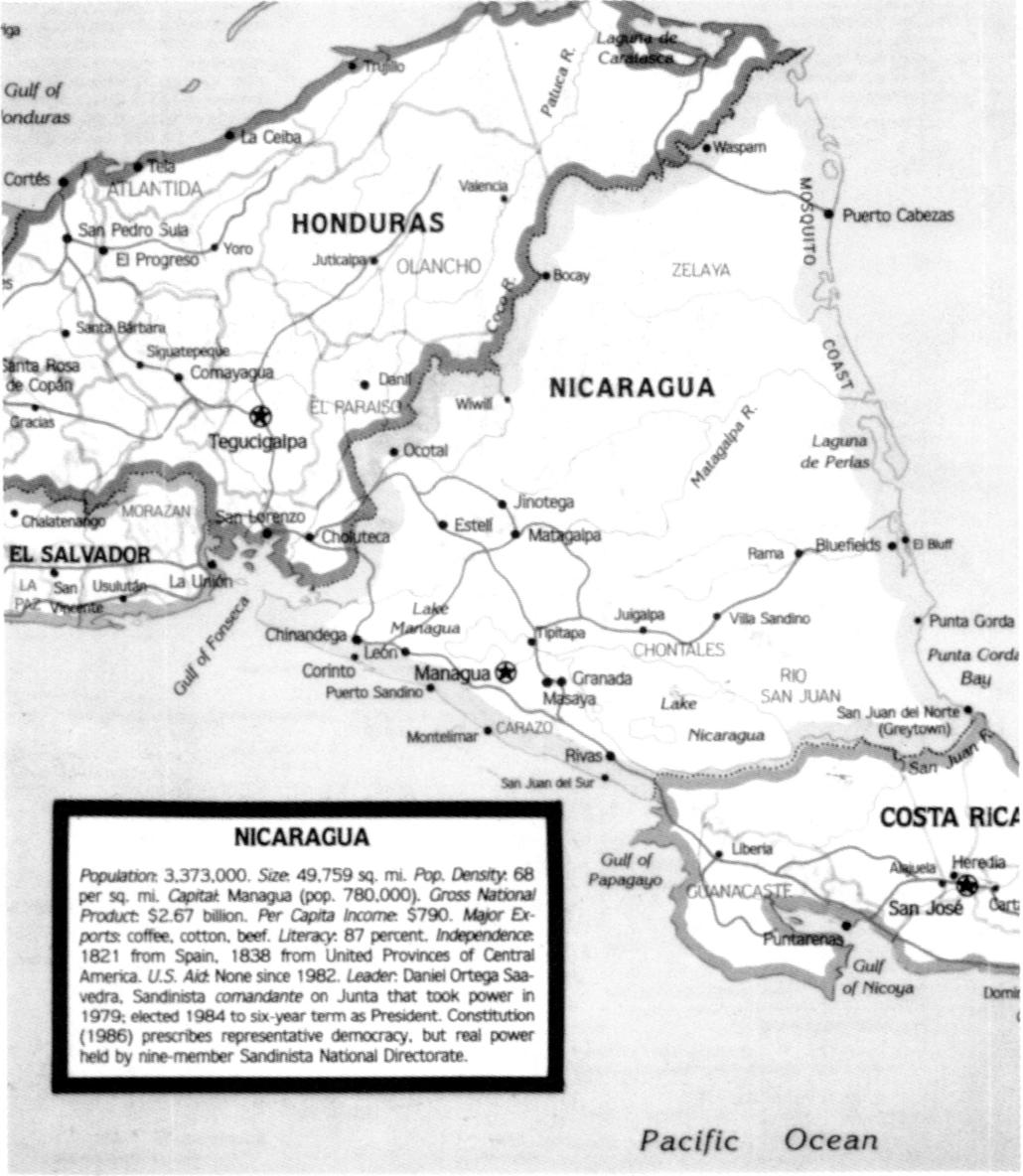

From the Wilson Quarterly, New Years 1988. Copyright 1988 by The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

LIFE

STORIES

~ OF THE ~

NICARAGUAN

REVOLUTION

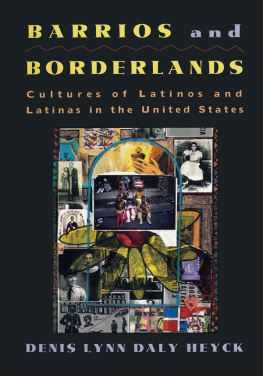

Denis Lynn Daly Heyck

Published 1990 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1990 Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

Life stories of the Nicaraguan revolution / [edited by] Denis Lynn

Daly Heyck. p. cm.

ISBN 0-415-90210-X.ISBN 0-415-90211-8 (pbk.)

1. NicaraguaHistoryRevolution, 1979Personal narratives. 2. NicaraguaPolitics and government1979 3. NicaraguaSocial conditions1979 4. NicaraguaEconomic conditions1979 5. NicaraguaBiography. I. Heyck, Denis Lynn Daly.

F1528.L52 1989

972.85053dc20 89-10319

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data also available

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-90211-3 (hbk)

Contents

I. Political Lives

II. Religious Lives

III. Survivors Lives

Life Stories is the work of a great many people, both here and in Nicaragua, to whom I am deeply grateful. First, I would like to thank everyone whose biography appears in this work for being so open and forthcoming. I owe a tremendous debt of thanks to those individuals in Nicaragua, some of them very good friends, who extended special courtesies to me in arranging introductions: Reinaldo and Gloria Tfel, Miriam Lazo, Comandante Leticia Herrera, Sr. JoEllen McCarthy, BVM, doa Violeta Chamorro, Msgr. Oswaldo Mondragon, Luis Flores and Luz Marina Flores.

In the U.S., first thanks go to my good friend Ted Copland who helped me understand Nicaragua and who encouraged me by his interest and example. For additional assistance, I am indebted to Carlos Tiinnermann, Frank Safford, Jon Pattee, Mercedes Knight, Walter Urroz, Carol Pazera, Joan Costa, and to various members of the Ecumenical Refugee Council of Milwaukee, expecially Sallie and Bob Pettit.

For his most helpful reading of the manuscript, I am deeply grateful to Alexandrino Severino. My colleagues Katen OShea and Sr. Mary Murphy, BVM, each contributed to this undertaking in important ways and deserve much recognition. Special thanks go to my editor, Jay Wilson, for his initiative and interest, and to Karen Sullivan and Michael Esposito, also of Routledge, for their careful and conscientious handling of the manuscript during the publication process.

Thanks to Hunter and Shannon Heyck, my children, for their interest in my work and their enthusiastic support throughout this project. My most profound thanks, however, must go to Bill Heyck who believed in the value of Life Stories at every step of the way. His numerous, insightful readings, and his consistently sound, objective advice kept me on course, and his vision enabled me always to keep sight of ultimate goals.

The inevitable errors, including those in translation, are my own.

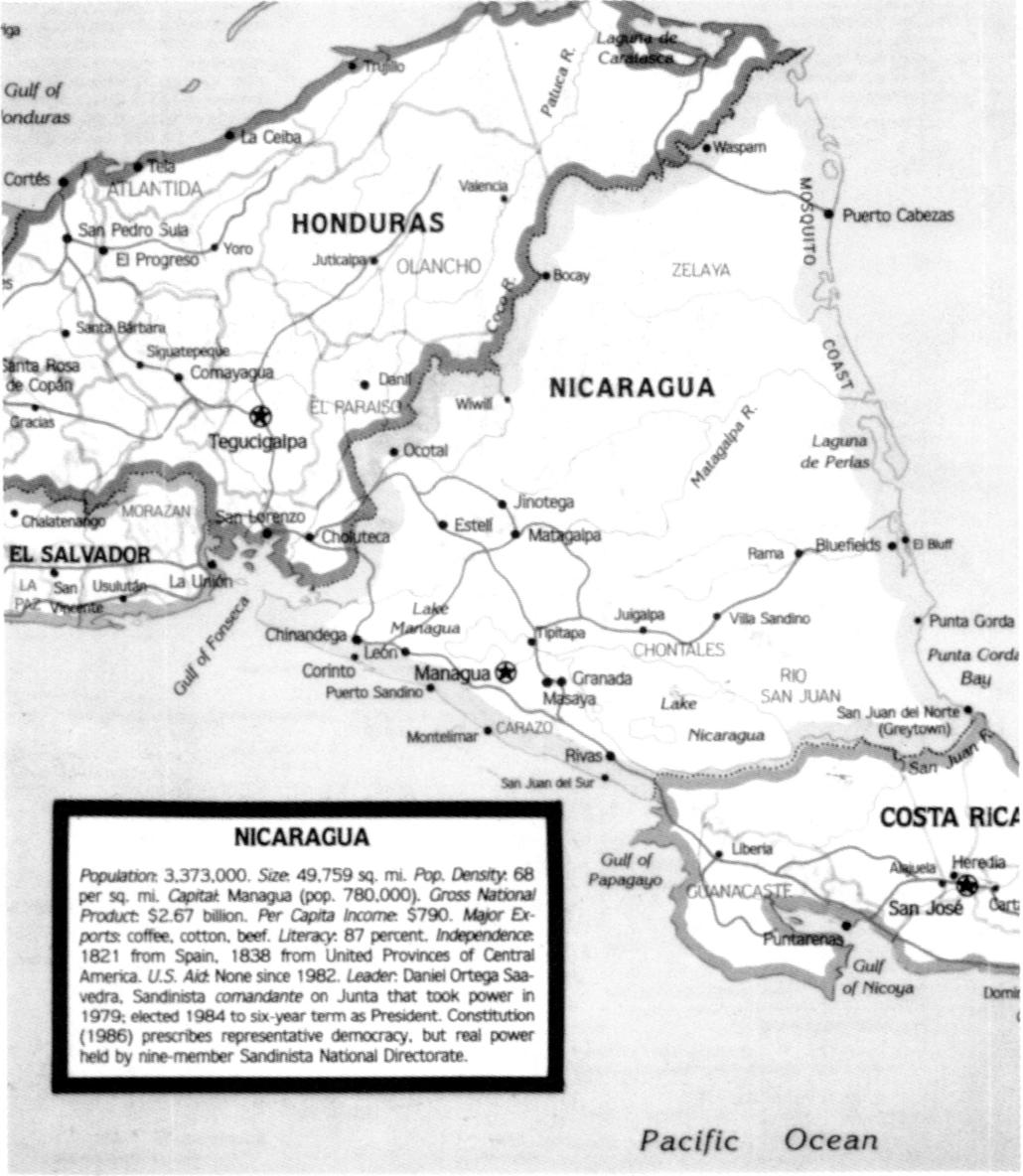

The purpose of this work is to illuminate the experience of the Nicaraguan people during the Sandinista Revolution. This book is not an analysis of the clash of social or political forces, nor is it an apology for, or a denunciation of, the Sandinista government. Rather, it is a portrayal of the human dimension of the current conflict, of what it is like to be alive in Nicaragua today.

The United States, for better or worse, has chosen to intrude in the Nicaraguan revolutionary process. It follows from this fact that we North Americans ought to do what we can to understand the situation more fully, for the assertion of power carries heavy responsibility. Yet polls as late as August 1988 indicated that the majority of U. S. citizens surveyed thought that their government was supporting a democratic regime in Nicaragua against communist rebels. Human lives hang in the balance of our ignorance.

There are many aspects to the Nicaraguan problem, some of which already have been widely discussed in books and articles, the global or strategic; the ideological; the economic; the historical; the military and the combat experience; the social and cultural, including the role of religion, the status of women, the place of poetry and the promotion of the arts, for example. This book seeks to communicate the human dimension; hence it allows the Nicaraguan people to tell their own story in a collective autobiography, a mosaic of hope and fear, triumph and tragedy.

Most of these life stories were collected in a series of conversations in Nicaragua during the summer and fall of 1987, while a few were gathered in the United States as early as 1986 and as late as 1988. Everyone with whom I spoke expressed him or herself freely. As will be obvious, no one felt any hesitation about talking candidly to me, just as they speak openly and with great animation to each other. Nicaragua is known as a nation of poets. Certainly nearly everyone I spoke with was highly verbal and articulate, whether they were formally educated or not.

I have chosen to group the stories that follow into three categories, political lives, religious lives, and survivors lives, according to what emerged as the most basic value in each persons life, the wellspring of their thoughts and actions. Every life story has many themes. But the one that has strongest claim to authenticity is a persons own perception. What is presented here is each individuals sense of his or her story as it has unfolded during the Somoza regime and the Sandinista Revolution.

It was sometimes difficult to classify people as either religious or political, rather than both/and, for in Nicaragua today these categories are by no means mutually exclusive. On the contrary, they are overlapping designations that reflect the fluid and complex reality of life. What was not difficult was to recognize the power of these two overarching values for the majority of the people with whom I came into contact.

As for the third category, survivors, it is intended to suggest the large number of people for whom the entire revolutionary experience has meant principally dealing with a new situation not of their making, like it or not. Some are coping by leaving; others, by staying; some, by criticizing; some, by supporting; others, by accommodating themselves to the new order. The people in this group are, above all, realists. For them, political and religious considerations, though very important, take a back seat to practical matters.

Any revolution is the conjunction of thousands upon thousands of individual biographies. This was never more the case than in the Sandinista Revolution, because although not everyone was involved in the revolutionary effort or in the later opposition to it, everyone in Nicaragua