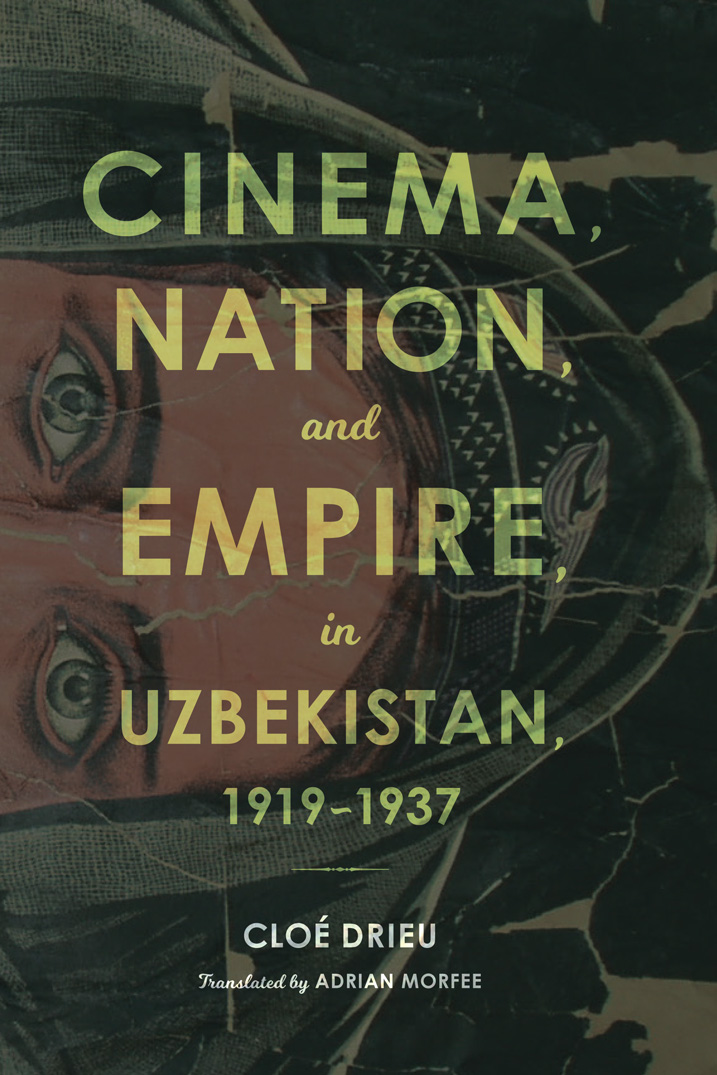

CINEMA, NATION, AND EMPIRE IN UZBEKISTAN, 19191937

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Originally Published as:

Fictions nationales. Cinma, empire et nation en Ouzbkistan (19191937)

ditions Karthala Paris, 2013

English Language translation:

2018 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Drieu, Clo, author. | Morfee, Adrian, translator.

Title: Cinema, nation, and empire in Uzbekistan, 1919-1937 / Clo Drieu ; translated by Adrian Morfee.

Other titles: Fictions nationales. English

Description: Bloomington, Indiana : Indiana University Press, [2018] | Revised and expanded from the original French. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018019384 (print) | LCCN 2018025311 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253037855 (e-book) | ISBN 9780253037831 (cl : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780253037848 (pb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion picturesUzbekistan. | Communism and motion picturesUzbekistan. | Motion picturesSocial aspectsUzbekistan. | Nationalism and communismUzbekistan.

Classification: LCC PN1993.5.U9 (ebook) | LCC PN1993.5.U9 D7513 2018 (print) | DDC 791.4309587dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019384

1 2 3 4 5 22 21 20 19 18

To my daughter Ellie

Contents

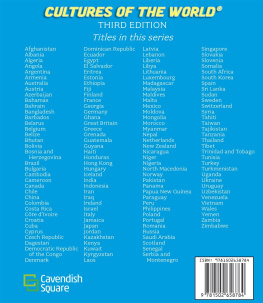

T HE SOURCES USED for this work are predominantly Russian but also include works in Turki (Uzbek), which used four different writing systems over the twentieth century: Arabic script until 1929 (with the reform in the mid-1920s advocating that long vowels be indicated), Latin script (192940), Cyrillic script until 1993, and since then, Latin script once again. Diacritics have not been used for the transliteration system for simplicity.

The following concordances have been used for Cyrillic alphabets (Russian and Uzbek):

The following have been used for the Latin alphabet (Uzbek 192740):

And these have been used for the Arabic alphabet (Uzbek until 1929):

The most frequently used names are transcribed in their habitual form. The letter j is used for the dj soundfor instance, in Khojaev (Khodjaev), Jadid (djadid), and Andijan (Andidjan).

P UBLIC READINGS WITH magic lantern images were held at Tashkent gymnasium and then at the public library. Among the measures taken to enable indigenous men of learning to discover modern science, the most spectacular trials with electricity were held on several occasions in the gymnasium, producing a great impression on the Muslim scholars of Tashkent. Afterward brochures were produced and translated by the editors of the Tuzemnaia Gazeta and read out for the auditors. One of these readings in Samarkand met with particular success and was described by an eyewitness in the following terms:

At eight in the evening on March 18, 1901, at the height of the Muslim festival of Kurban Bayram, for the very first time, in the Shir Dor madrasa, a reading took place accompanied by obscure images, organized by the Samarkand Public Reading Circle. And now, fifteen hours after this reading, I still cannot clearly picture what this evening wasI cannot speak calmly of what I witnessed for the first time in my life, for I am still under the influence of the enchanting nature of the evening in question. Yes, the strength and clarity of the images made this an essentially extraordinary event in our Russian life, and even more so in the monotonous lives of the natives of Samarkand. I am convinced that since the days of Tamerlane and Ulugh Beg, the madrasas of Registan have never seen such a large number of spectators within their walls as there were yesterday to be found in the Shir Dor madrasa.

The theater was formed by the large, square courtyard of the madrasa, paved with marble slabs and surrounded by two-story buildings with numerous balconies and arcades in the Moorish style, entirely covered with magnificent ceramic tiles dating from the days of Tamerlane, which have remained unaltered for centuries. The screen for the obscure images was lit by the powerful light of an acetylene lamp, recently received by the Public Reading Circle, and carefully positioned so that the images on the screen were visible from any point in the theater.

There was a reading, for the first time, of Tolstoys work What Men Live By in a good translation into the Sart tongue. The reading was given by the young mullah Mahmud. It was not easy for him that evening to win the well-deserved honors that normally go to the first reader. He read from 7:30 until 9:30, during which time he left his place to others about five times in order to recover his strength. He read so loud, as only a mullah with healthy lungs can do, calling with his voice that resounded like a bell summoning his countless faithful to prayer! And despite all that, the size of such an open-air theater; the acoustic conditions, which were ill-suited to a reading; and the almost unbearable hubbub of several thousand excited spectators were so disagreeable for the reader that the powerful and expressive declamation pouring forth from his lips all but died on reaching the back rows of those present. The spectators were all on the parapets and balconies and in all probability could not properly hear the reader bawling out at the top of his lungs. A final reward, comprised of a miraculous spectacle of flying birds, was out of sight for those sitting lower down.

How many and numerous were the people? It can be worked out based on the surface area, which was about 850 square meters. It was entirely filled by children (at the front) and adults standing or sitting behind them. It may be said without exaggeration that there were at least 4000 people there, and about 5,000 counting those on the balconies. As may be expected, most of the public were Muslims from the towns, indigenous Jews, Persians, Russians, and Armenians.

Admittance to the reading was free.... Before the reading began, V. Medinskii [the military governor general] congratulated the indigenous Mohammedans on this day of festival and suggested raising a cheer to the long life of the emperor and sovereign. He hoped the natives would appreciate the true worth of this public reading held for them and that they would be as attentive to the readings as they were currently being. These words from the leader of the province were welcomed with long and deafening hurrahs from the crowd of several thousand people. An hour before the reading began, the Zerabulavskii Battalion wind band... played on Registan Square and then in the theater itself. The band may not have been complete, but what an incredible and joyous spirit was awakened among this countless and beturbaned public by the powerful, enchanting, and divine sounds of our Russian music resonating within the ancestral walls of Shir Dor!