2015 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

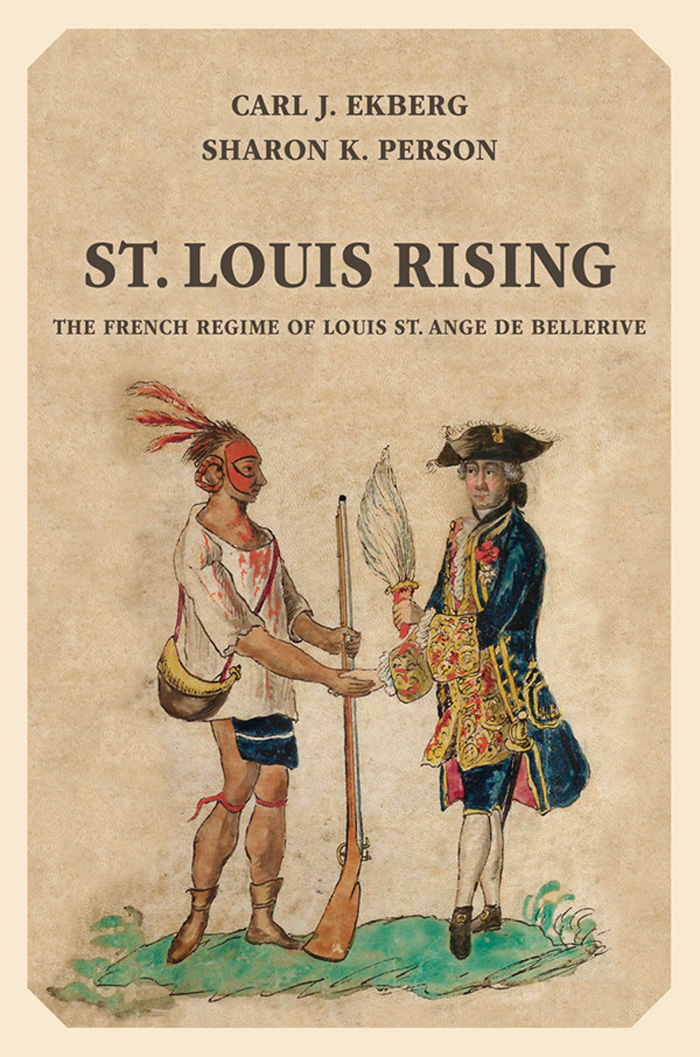

Frontispiece: Kerlrec Indian commission. This exquisite tableau is the ornamentation on a commission tendered to the Cherokee chief Okana-Stot by Louisiana governor Louis Billouart de Kerlrec in February 1761. The Cherokees were sometime enemies of the French, but Kerlrec took his diplomatic duties seriously and sought out their friendship. The French royal coat of arms is at the top, on the left is that of Louisiana, and on the right that of Kerlrec. Courtesy National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ekberg, Carl J.

St. Louis rising : the French regime of Louis St. Ange de Bellerive /

Carl J. Ekberg and Sharon K. Person.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03897-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-252-08061-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09693-8 (e-book)

1. IllinoisHistoryTo 1778. 2. Saint Louis (Mo.)History18th century. 3. Saint-Ange de Bellerive, Louis Groston de. 4. Frontier and pioneer lifeIllinois. 5. Frontier and pioneer life MissouriSaint Louis. 6. FrenchIllinoisHistory18th century.

I. Person, Sharon. II. Title. III. Title: Saint Louis rising.

F544.E39 2015

977.86602dc23 2014031907

St. Ange has served since he was a child, and became a captain on October 15, 1748. He is an excellent officer for that region [Upper Louisiana], especially regarding the Indians, whom he leads and guides at his will. Hes a man of absolute probity, a zealous servant of the king, and has always regarded commercial activities as beneath him.

Governor Louis Billouart de Kerlrec, 1759

PREFACE

The roots of this book go back several years, when Helen Vall Crist suggested that Sharon and Carl collaborate on a research project dealing with early St. Louis; our gratitude for this gesture of benevolence continues to inspire us. After dinner at Anne and Rodney Johnsons historic home in Webster Groves, Missouri, in June 2011, we began an e-mail conversation about the extraordinary 1766 St. Louis manuscript census. In our exchange of ideas, we soon concluded that it was a document worth scrutinizing, annotating, and publishing. Then there was the thought that the 250th anniversary of St. Louiss founding was coming up soon and that, as historians, we wished to make some contribution to the occasion. Deeper in our minds was the suspicion that the rich archives of the Missouri History Museum had manuscript collections pertaining to early St. Louis that had not been fully exploited. And, finally, working our way tentatively into recent historical literature about the American West, we discovered remarkable neglect of the colonial Illinois Country, of which St. Louis was a part and without the existence of which St. Louis would never have developed. For all these reasons, we decided to plunge ahead, and we began research on what we, with increasing confidence, envisioned as a major revisionary book.

At the outset, we must acknowledge that this study is an astringent critique of much that has been written about St. Louiss early years. The citys history has proved irresistible to writers of many stripes and varying degrees of talent, each of whom has told the story from his or her own perspective, with his or her own particular biases and prejudices. And the 250th anniversary of the citys founding (2014) has provoked a flurry of additional commentary, opinion, scholarship, and writing about early St. Louis. Whatever the diversity of views, however, all versions of early St. Louis history have one thing in common: they focus overwhelmingly on the importance of Pierre Laclde and Auguste Chouteau. The further we delved into original manuscripts, the more dubious we became of that standard formulation, for we discovered that Lacldes name appears but rarely, and Chouteaus even more rarely. The seeds of Chouteaus eventual prominence were surely there during the 1760s, but primary sources do not reveal them. After combing the archives for many months, we mutually agreed that the story of St. Louiss founding and early days cried out for retelling.

In 1910 the St. Louis Field Club, which had been founded in 1897 as a nine-hole golf club, reconstituted itself as a full-fledged eighteen-hole country club, and a controversy arose over selecting a name for it. The matter of choosing a name for the new club had been under discussion for several months. Nearly every club member had his individual preferences and aversions. It was apparent from the beginning that these divergencies of view could not be reconciled through discussion. To avoid an acrimonious debate, the club decided to conduct a secret poll, and 169 members participated. Bellerive (for Louis St. Ange de Bellerive) was their overwhelming preference for a name; Laclde ran a distant fourth (behind Brookwood and Pontiac), and Chouteaus name did not make the short list. It is apparent that those old duffers with their handlebar mustaches, plus-fours, and hickory-shafted golf clubs knew a little something about the history of early St. Louis and about the towering importance of the Canadian-born man who governed the French outpost during its formative years.

The book that follows is complex. It is a history of the Illinois Country between 1720 and 1770, an overview of the important GrottonSt. Ange family, a biography of Louis St. Ange de Bellerive, and a study of St. Louiss formative years as a French outpostincluding the roles of women, slaves, farmers, carpenters, and fur traders. It is western history, southern history, midwestern history, and colonial history; although containing much about Indians, it is not a study in ethnohistory per se, for neither our sources nor our inclination took us in that direction. Because of our texts complexity, we have relied on assistance from a wide range of persons, without whose help the book would never have appeared in its present form. First, the indispensable archivists and librarians: Larry Franke at the St. Louis County Library; Dennis Northcutt, Molly Kodner, and Jaime Bourassa at the Missouri History Museum in St. Louis; Mary White and Sarah Elizabeth Gundlach at the Louisiana State Museum in New Orleans; Richard Day, authority on all things pertaining to colonial Vincennes; Emily Lyons at the Randolph County Courthouse in Chester, Illinois; Father Kenneth York at the diocesan archives in Belleville, Illinois; and Marie-Paule Blasini at the Archives Nationales dOutre Mer in Aix-en-Provence. We bombarded these custodians of the past with many idiosyncratic requests, and they came through unfailingly and with good humor.

American Indian studies has become such a large, diverse, and contentious field that we were obliged to consult persons more expert than we. Many e-mail dialogues with linguists and cultural historians Carl Masthay and Michael McCafferty have proved endlessly useful. And Carolyn I. Gilman of the National Museum of the American Indian helped us sort out the George Catlin paintings that are reproduced in this book. Kathleen Duval generously took of her time to critique the chapter on slaves, African and Indian. Material culturefurniture, housewares, architecture, building practices, clothing plays an important role in our book, and again we have relied on expert assistance: Robert F. Mazrim of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey; Anne Woodhouse of the Missouri History Museum; Maurice Meslans, with his formidable knowledge of early silversmiths and silverware; Peter Moogk, self-effacing cognoscente of French Canadian building ways; Jay Edwards of Louisiana State University, subtle anthropologist of Creole architecture and building practices. Gilles Havard lent his expertise regarding fur-trade complexities, as did U.S. Appellate Judge Morris S. Arnold regarding legal nomenclature.

![Louis de Montfort - The Saint Louis de Montfort Collection [7 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/265822/thumbs/louis-de-montfort-the-saint-louis-de-montfort.jpg)

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.