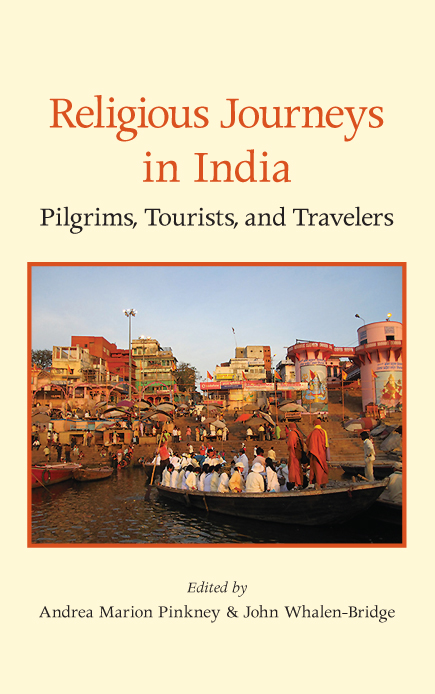

Cover photo of the boat trip on the Ganges courtesy of Joanna Cook.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2018 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pinkney, Andrea Marion, editor. | Whalen-Bridge, John, editor.

Title: Religious journeys in India : pilgrims, tourists, and travelers / edited by Andrea Marion Pinkney & John Whalen-Bridge.

Description: Albany : State University of New York, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016040639 (print) | LCCN 2016043152 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438466033 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438466040 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Pilgrims and pilgrimagesIndia. | TourismReligious aspects. | TourismIndia.

Classification: LCC BL2015.P45 R45 2018 (print) | LCC BL2015.P45 (ebook) | DDC 203/.50954dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016040639

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated to Nancy J. Ellegate

(19592015)

Introduction

New Motivations for Religious Travel in India

A NDREA M ARION P INKNEY AND J OHN W HALEN -B RIDGE

P ilgrimage routes, flows of travelers, and sacred sites are imbued with the kinesthetic and transformative possibilities at the core of religious experience. Yet all the instruments agreesuch experience is hard to measure: Pilgrimage may be thought of as extroverted mysticism, just as mysticism is introverted pilgrimage. The pilgrim physically traverses a mystical way; the mystic sets forth on an interior spiritual pilgrimage (Turner and Turner 2011, 33). In undertaking religious travel, personal motivations for religious travel are complex, contingent, and cover the spectrum from introversion to extroversion, physical travel to inward journeying, and so on. How then shall we separate religious journeying from social and leisure travel?

While religious tourism is evidently motivated either in part or exclusively for religious reasons, Gisbert Rinschede maintained that religious tourism overlaps with cultural and heritage tourism, typically fulfilling several motivations and other subordinate goals (Rinschede 1992, 52). In India, the National Sample Survey Office of India (NSSO) reported the compound motivations of domestic travelers under categories ranked by leading purpose, or as the motive but for which he/she would not have undertaken the trip. As reported in 20142015, the highest-ranking purpose for domestic travel in India is social (85.9%), followed by religious and pilgrimage (8.3%). In characterizing religious tourism in nations with developing economies, Rinschede argued that for many, religious tourism offers the only possibility of travel (1992, 52). While this may hold true elsewhere, it is important to note that this scenario does not readily transfer to India. This is because modern travel infrastructure was developed in South Asia within decades of its emergence in Europe. Today, Indias transportation infrastructure includes vast inland waterways, one of the worlds largest and most heavily used passenger rail systems, a robust domestic air network, and roads that traverse routes used in antiquity to alpine engineering marvels numbered among the worlds highest navigable motorways.

Modern travel networks arose in India from the mid-nineteenth century onward, with the construction of the first passenger railway line (18531854), approximately a quarter century after steam locomotive technology was introduced in Britain (1825). Subsequently, the railways rapidly transformed India by remapping river transportation systems and premodern roadways within the new colonial networks of empire, expanding the frontiers of the accessible world and creating public spaces that mingled people differentiated by social taxonomy, such as caste, religious communities, and ethnicities in unprecedented ways (Prasad 2016, 61). Looking ahead, the twenty-first-century rise and market penetration of discount airlines or low-cost carriers (LCCs), such as IndiGo, Jet Airways, and SpiceJet, have further expanded access to the global transportation network for citizens residing in secondary population centers and opened new routes of access for international and regional visitors to India.

At present, most domestic tourist visits in India continue to be undertaken by bus in rural areas (50%), while the bus and train are used almost equally in urban areas (34% and 31%, respectively) (NSSO 2016, Statement 3.13a). Yet in contrast to the overall preference for bus travel, rural travelers took the train for nearly a third of all religious journeys (28%), while urban travelers used the train for nearly 70% of all religious journeys (with bus use falling from 34% to 11%

Mapping an Interdisciplinary Journey through Indian Religious Sites

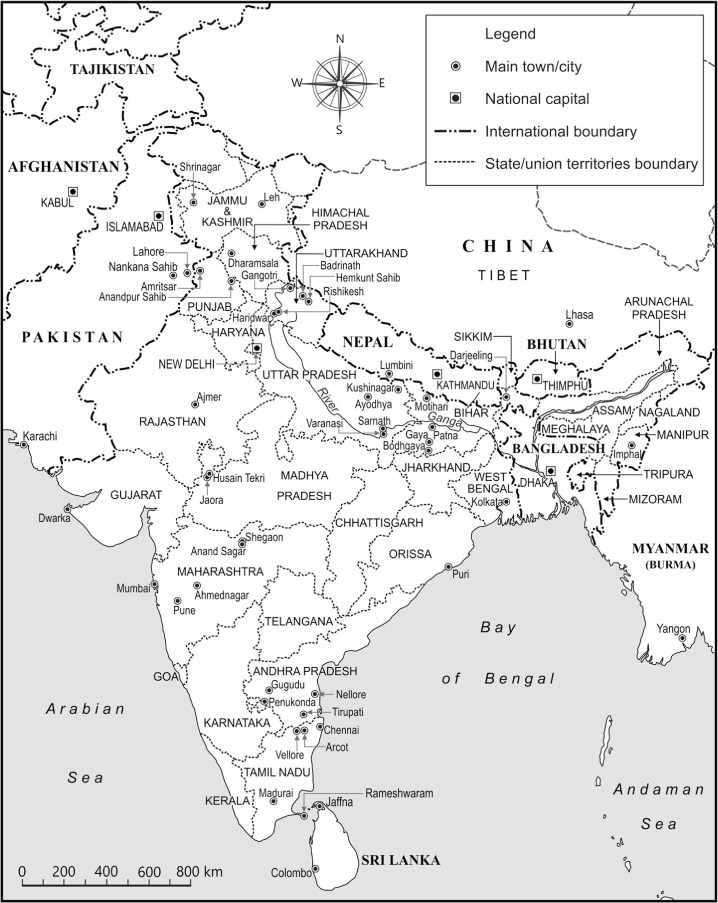

The essays in this volume offer perspectives on religious journeying in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Manipur, Uttarakhand, and Uttar Pradesh, and they engage Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, as well as those whose personal identity challenges such regional and community formations. In a mosaic of diverse contexts, we explore intersecting and evolving motivations for religious travel in Indiafrom exile and mission, to heritage and Hindutvaand discover new mappings of the sacred in interreligious and regional case studies from India.

All major sites discussed in this volume are located on map 1 (see , examines frameworks of Muslim pilgrimages in India. She shows that, for many Muslims in India, visits to important shrines like those found at Husains Hill (Husain Tekri) in Madhya Pradesh are articulated and accepted by some Muslims in ways that suggest that even in the modern, post-partition period, some South Asian Muslims exist within a spiritual landscape that posits more continuity than competition between Mecca and South Asia.