First published 2020 by Interventions Inc

Interventions is a not-for-profit, independent left wing book publisher. For further information:

Trades Hall Suite 68

54 Victoria Street

Carlton VIC 3053

Design and layout by Viktoria Ivanova

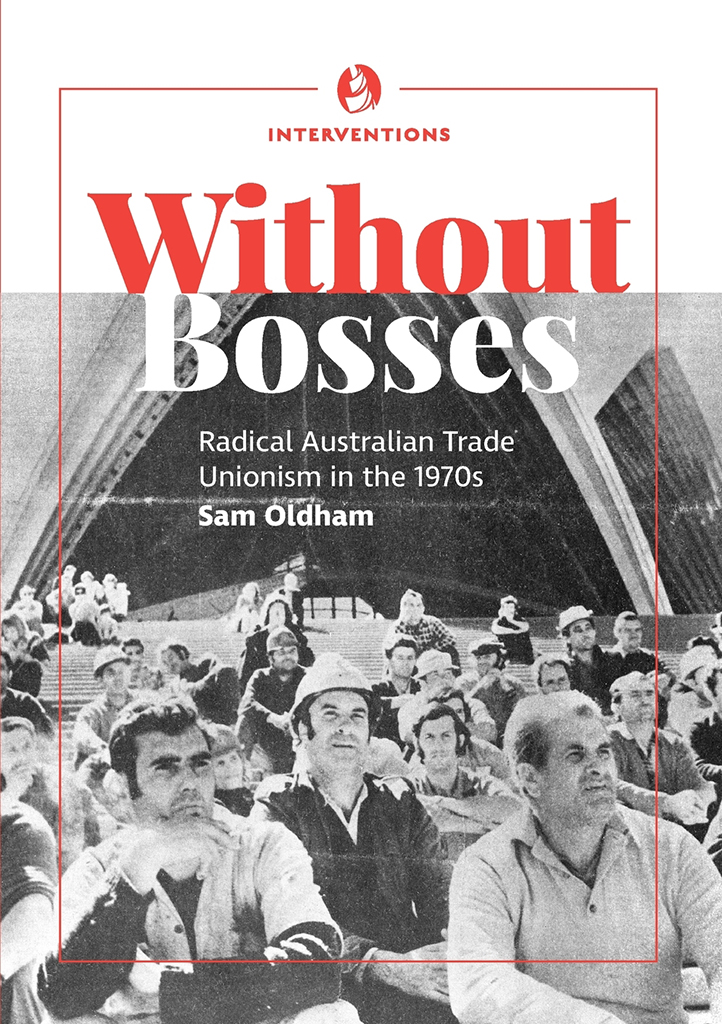

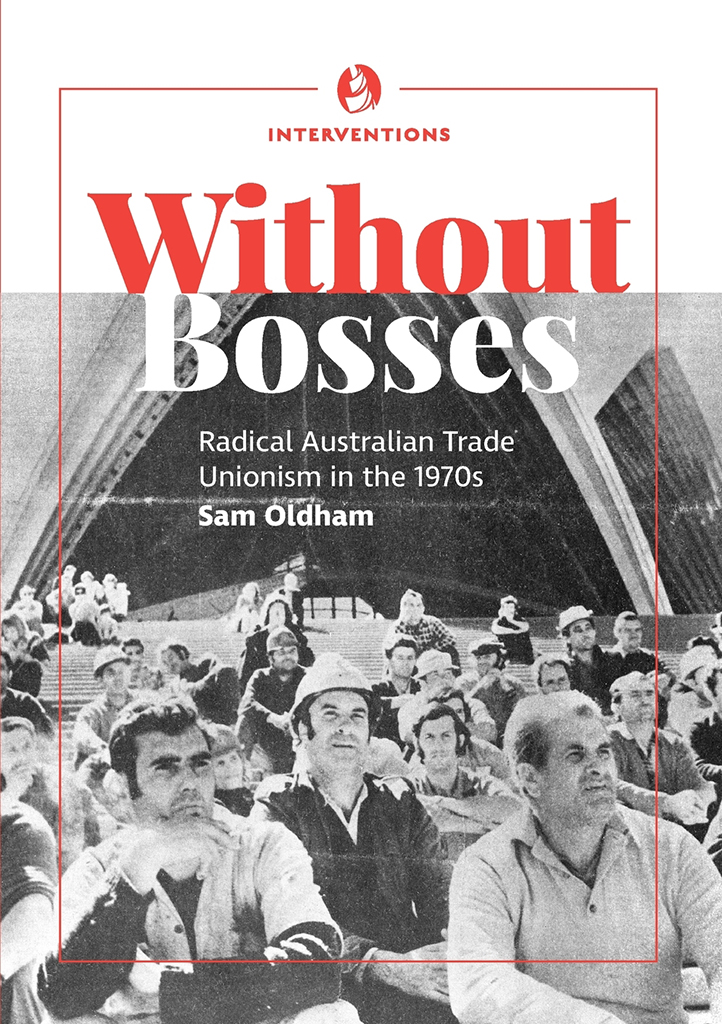

Cover photo from Tribune October 16-22, 1973, photographer unknown. Used with kind permission of The Search Foundation.

For those photographers whose images we used without permission, we tried to find you and couldnt and thank you for your wonderful contributions.

Author: Sam Oldham

Title: Without bosses. Radical Australian Trade Unionism in the 1970s

ISBN: 978-0-6487603-0-6: Paperback

ISBN: 978-0-6487603-7-5 (e-book)

Sam Oldham 2020

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968 (for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review), no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, communicated or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

All inquiries should be made to the author.

Interventions is produced on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of country throughout Australia and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. Their land was stolen, never ceded. It always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

It gives you a bit of an idea of how it would be to work under socialism, without bosses.

NSW coal miner & unionist, 1972

The book is dedicated to my grandfather, Hilary Scott, a retired carpenter who would have read it with interest. He passed away as it was being prepared for publication.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the support of numerous people. I would like to thank Janey Stone very warmly for accepting the manuscript on behalf of Interventions, for coordinating the project and for leading me through the publication process with patience. My sincere gratitude goes to Michael Lazarus for rescuing the book from limbo and delivering it to Interventions. I am grateful for his feedback on the draft and for his encouragement along the way. My thanks go to Liz Ross for her painstaking efforts in reviewing the final manuscript and for her invaluable feedback. I would like to thank everyone involved with Interventions for publishing the work and keeping the tradition of radical independent publishing alive.

Without Bosses began life some years ago as a Master of Arts thesis at Monash University. It would not have been possible without the help of my dutiful and patient thesis supervisors, Steve Wright and Erik Eklund. I also owe a debt of gratitude to librarians and archivists at Monash University, the University of Wollongong, the State Library of Victoria, the State Library of New South Wales, the National Library, and Katie Wood at the University of Melbourne Archives. I would like to thank all the trade unionists, active and retired, who agreed to talk to me for the project. There are too many to count, but a short list includes Frank Cherry (with the support of the AMWU), Ken Purdham (with the support of the ETU), Malcolm MacDonald, Andrew Dettmer, John Cleary, Jerome Small, George Koletsis, Graeme Watson, Ron Carli, Nando Lelli, Mick Tubbs, Jack Mundey, Pat Johnstone, John Brunskill, Danny Gardiner and Tony Robins.

FOREWORD

Workers control is a term that can mean many things. From democratic self-management, to worker-ownership, to worker occupations and even strike actionall of these types of actions and formations capture a similar urge. Throughout history, working people have sought to exercise control over their working lives and the economic decisions that affect them. In the present, it seems like this urge has been lost to other concerns. Neo-fascism, the climate crisis, inequality and large-scale unemployment all tear at the fabric of social life. In much of the world, where even the principles of political democracy seem in need of protection, the idea of economic democracy seems distant. The idea that our workplaces should be under anything but the autocratic control of bosses and managers remains difficult to shake.

This book gives an account of one period during which the authority of employers and managers was shaken. It shows that the decade from the late 1960s in Australia was far and above the most significant period of trade union power and activism in that country, during which workers made serious incursions into the powerful decision-making systems that normally governed their lives. As a result of democratic trade union power, that seemingly inalienable right of bosses, managers, and governments to control the lives of working people was openly challenged. As this book shows, workers in a range of industries challenged the prerogatives of their employers, rejected the official industrial relations apparatus, and defied attempts by the state to police and restrict their activities. Workers experimented with self-management of their workplaces, forms of union and worker-ownership, and new types of strike action over a broad range of concerns. Rather than separate from various social, political and environmental struggles, the workers movement saw itself as crucial to them.

This was an international phenomenon during the early 1970s. The Institute of Workers Control in Great Britain was established to trace the radical developments in labour unions occurring there from the late 1960s. Radical labour struggles occurred in many countries throughout Europe and the Americas, shaking the foundations of the employing classes and state power.

In more recent times, the largest strikes in world history have occurred in Third World manufacturing centres upon which Western consumers now depend. In developed countries, ideas of workers control endure in pockets of economic life. In American cities and towns affected by offshoring and deindustrialisation, worker-owned cooperatives have proliferated, intersecting with trade unions in powerful and innovative ways. As Oldham shows, the legacy of the 1970s endures in Australia, with the countrys construction union declaring an environmental green ban on the proposed redevelopment of Sydneys Bondi Pavilion as recently as 2017.

The book demonstrates that labour militancy and the practice of worker control is not an antediluvian form drawn from the early 20th century, but a compelling force in more recent times with a powerful legacy in the present. Building a workers movement requires organisation and careful strategic thinking. Though hard work lies ahead, activists in the present should take heart in the fact that the urge for workers power is never far from the surface.

Interventions is produced on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of country throughout Australia and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. Their land was stolen, never ceded. It always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

Interventions is produced on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of country throughout Australia and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. Their land was stolen, never ceded. It always was and always will be Aboriginal land.