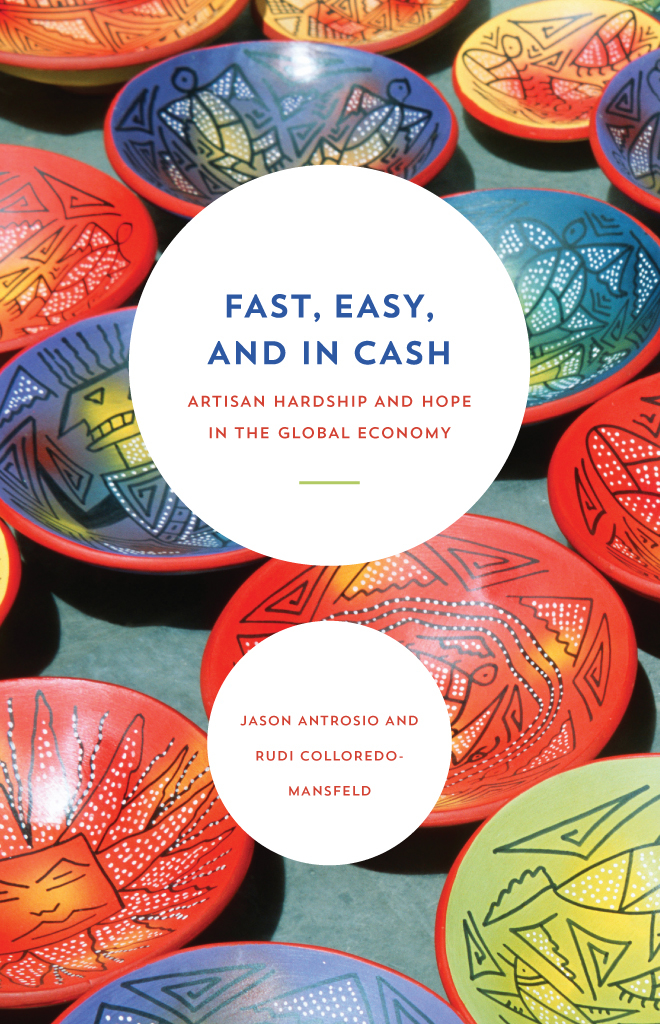

Jason Antrosio is associate professor of anthropology at Hartwick College in Oneonta, New York. Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld is professor and chair of anthropology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2015 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30258-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30261-4 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30275-1 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226302751.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Antrosio, Jason, author.

Fast, easy, and in cash : artisan hardship and hope in the global economy / Jason Antrosio and Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-30258-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-30261-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-30275-1 (ebook) 1. ArtisansAndes Region. 2. ArtisansAndes RegionEconomic conditions. 3. Cottage industriesAndes Region. 4. Andes RegionEconomic conditions21st century. I. Colloredo-Mansfeld, Rudolf Josef, 1965 author. II. Title.

HD 9999. H 363 A 63 2015

331.7'94dc23

2015007905

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Half a world away from the Andean towns of this research lies the great Kumasi Central Market in Ghana. The anthropologist Gracia Clark has written at length about the dynamism and unruliness of Kumasi Central Market, where in the 1980s some twenty thousand traders worked daily selling food, services, crafts, and imports. Seventy percent of these operators were women. Their stalls, tables, and stores spread in a living carpet of energetic, even desperate commercial initiative (Clark 1994, 1). Yet the Kumasi Central Market was also the place where young mothers worked in a committed but less frenetic way. They undertook what was called Nursing Mother Work. These were market niches women created to provide a reliable income during a crucial phase of a womans life when the urgency of work is driven on by the urgency of caring for an infant or toddler. But childcare and market work were not in conflictchild care and work went together, as mothers found their place in the street or market, selling with a new sense of purpose. In Clarks phrase, motherhood demands work, even if it constrains it (1999, 723).

Clarks work and phrasings came to mind as we pursued this research, went to conferences, and wrote up our results. Sometimes she came to mind for her creativity. Clark often collaborated with women who worked in Andean marketplaces, like Florence Babb, Linda Seligmann, and Mary Weismantel, who were doing incredibly innovative research on markets, gender, and identity. For those of us documenting agrarian economies in the 1990s, it seemed as if they were working in color at a time when economic anthropology was being churned out in black and white.

The idea of Nursing Mother Work also resonated because our own research had become a kind of fathers work, an occupation that in its own way was both urgent and constrained. As we began a collaborative project in 2004, we were both husbands and fathers. Our spouses literally had to secure Nursing Mother Work as they launched careers in the college towns where we had landed, on the fortunate side of the academic job market (which looked more and more like the winner-take-all payout described in chapter 3). Our children were toddlers or infants, or on the horizon, as we mapped out a comparative project for Otavalo and Atuntaqui. Up to this point in our careers, our writing had drawn on doctoral fieldwork involving the classic solo, immersive ethnographic techniques that have long marked anthropology: living in the research community, joining in work and daily domestic life, dashing off to a community meeting, town festival, or weekly market, and so on. Now, we had teaching jobs, children, and working spouses.

Only by teaming up would we be able to tackle the economic issues unfolding in these Andean towns. Usually our research periods in Ecuador were measured in weeks, not months. And if we were lucky enough to have our families with us during our research, our days would be split between research and family outings. To capture the social, cultural, and political implications of the economic changes we tracked, we needed to find new ways to participate in the flow of action in Otavalo, Atuntaqui, and elsewhere. The solutions we found became integral to understanding the stories in the chapters that follow.

In part, we had to be patient and parcel out our work over several summers and multiple return trips. We also grew to rely on a diverse set of collaborators, institutions, and research assistants. Together these collaborations and regular returns helped reveal how the innovations and disruptions that we documented in our initial research rapidly evolved. Thus, in Atuntaqui, we sought to improve our list of family firms in the casual clothing business by going out to find the enterprises that showed up on various economic development reports. Working with the chamber of commerce to recruit a field assistant from Atuntaqui, we partnered with Byron Beltran in 2006 to develop a map of the store and workshop locations. By returning to Atuntaqui and reconnecting with Byron three more times over the following five years, we were able to update the map and show how rapidly investment in apparel was reshaping the center of the city. And in Otavalo in 2004, we worked with the Union of Indigenous Artisans of the Centenario Market-Otavalo (la Unin de Artesanos Indgenas del Mercado Centenario-Otavalo, or UNAIMCO) to hire two research assistants, Myriam Campo and Toa Maldonado, to help with a producer survey focusing on fashion and cultural identity in designs. The original purpose in 2004 was to identify whether trades that had a strong cultural identity were more economically resilient. Working with Toa and others on return visits in 2005, 2006, and 2007, we tracked the ongoing life of the original designs. The longitudinal study gave us more insight into both innovation and the identity of the marketplace. Steady, committed, part time, collaborative, and long term was our modus operandi as fathers and, if it felt a constrained kind of ethnography, it also turned out to be very fruitful.

In Atuntaqui, officers and staff at the Chamber of Commerce of Antonio Ante (CCAA) supported our efforts year in and year out beginning in 2005. Diego Lopez, the director of the CCAA in 2004, helped forge our original connections, and his successor Santiago Salgado invited us to meetings, helped us recruit research assistants, and facilitated introductions to business operators. Diego Salgado, who served on the CCAA board, took the time to talk us through the issues they faced as they pursued more ambitious promotional events. And perhaps the most impactful support and advice came from Lili Posso, who worked her way up from secretary to director of the CCAA over the years of our project. Lili provided both crucial logistical support for our surveys and incisive commentary about the social world interwoven with the economic programs unfolding in Atuntaqui in the 2000s.