Acknowledgments

I offer special thanks to several individuals: Martin H. Belsky, Dean, the University of Akron School of Law, for his thoughtful and detailed editorial comments; David Cornsilk, former Managing Editor, Cherokee Observer, and founding member, Cherokee National Party, for offering his keen insights on Cherokee history; Ron Graham, Founder/President, Muscogee (Creek) Indian Freedmen Band, for providing historical and personal materials relating to the status of the Muscogee (Creek) Freedmen; Eli Grayson, President of the California Muscogee (Creek) Association, for enlightening me on his considerable efforts in behalf of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Freedmen; Davis D. Joyce, Ph.D., historian, for his engagement around issues of purpose and perspective, as well as his critical commentary; Robert Littlejohn, African-American Historical Society, Tulsa, for sharing his extensive collection of references and detailed knowledge of the African-American experience in Indian Country; and Marilyn Vann, President of Descendants of the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, for allowing me access to her impressive cache of documents and records and, more generally, for her passion for the Freedmen.

Thanks also to: Reuben Gant, Chief Executive Officer, Greenwood Chamber of Commerce; George Getchow, The Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Writers Conference of the Southwest at North Texas State University; Vanessa Adams-Harris, Muscogee (Creek) Nation citizen, advocate, and actress; Terry J. Ligon, Director of the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen Project; Jeremy Lynch, Park Ranger, Fort Smith National Historic Site, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior; Calvin C. Moore, J.D., Ph.D., Cleveland State University; Larry ODell, Historical Collections Specialist, Research Division, Oklahoma Historical Society; Loretta F. Radford, Esq.; Osman Sheikh, University of Oklahoma graduate student; Monetta Trepp, Muscogee (Creek) Nation citizen; Robert Trepp, Muscogee (Creek) Nation citizen and historian; Verdie Triplett, Founder and Contact Person, Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen Association; Angela Y. Walton-Raji, Webmaster and Editor, The African-Native American History and Genealogy Web Page; and Corporal Steve Wood, Tulsa Police Department.

Introduction

We learn from history that we learn nothing from history.

GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

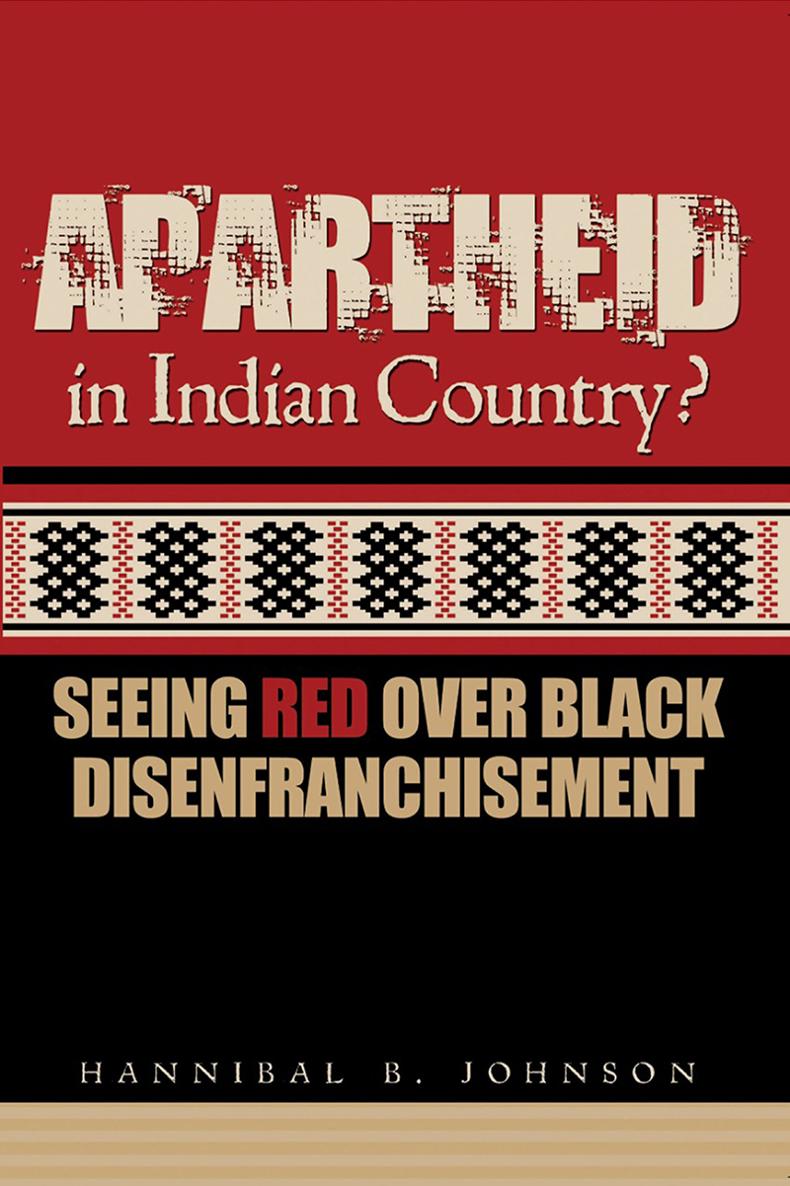

Apartheid in Indian Country?: Seeing Red Over Black Disenfranchisement focuses on the long and storied relationship between persons of African ancestry and Native Americans, As scholar William Loren Katz pointed out:

Those who have put history into books have emphasized differences between Africans and Native Americans. For example, they have stressed that Europeans encountered Indians as distinct individuals and members of proud nations, and Africans as nameless slaves. Little mention is made of the enslavement of Native Americans and nothing is said about the cultural similarities between the two dark peoples.

Katz asserts that this hypersensitivity to differences, real or imagined, between red and black people worked to the advantage of the dominant culture. Whites, he argues, exploited both populations.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson,

Others echo these same sentiments. For too long, critics urge, historians cast African Americans as bit players on the stage of the American drama, no less so in the acts recounting the Native-American experience.

[I]n the telling of Native-American history... historians have rendered African-American members of the Five Nations of the Southeastern United States [Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, and Chickasaw] as passive objects swept along in the tides of the great drama which is Native-American history. Existing solely as the reason for the struggle that led up to the Civil War in Indian Territory, they are seldom given their proper place as moral guides and political instigators in the struggle which came to define a people. This [is an] a historical and immoral treatment of history.

Recent developments further cloud our understanding of the enduring, nuanced relationship between persons of African ancestry and Native Americans. Controversy swirls around the tribal exile of African Americans with blood, cultural, and/or treaty ties to various Native-American tribes. Ties once thought to bind have loosened and frayed along color lines. Some cite ignorance of history, political demagoguery, and racism as among the chief facilitators of this unraveling of relations. How the United States dealt with these dynamic populations lies at the heart of the story.

The centuries-old interactions between the United States and various Native-American tribes have been fundamentally political government to governmentin nature. The European colonists who settled here regarded the original indigenous tribes they encountered as sovereign nations. That early solicitude for indigenous sovereignty Native Americans enjoy peculiar legal and political relationships with the federal government.

However, Native-American sovereignty, the subject of considerable scholarship and popular discourse, is both malleable and ephemeral. In the final analysis, this special kind of non-sovereign sovereignty a 1973 case, a federal court described the special status of Native-American tribes:

No doubt the Indian tribes were at one time sovereign[,] and even now the tribes are sometimes described as being sovereign. The blunt fact, however, is that an Indian tribe is sovereign to the extent that the United States permits it to be sovereignneither more nor less.

.......

While for many years the United States recognized some elements of sovereignty in the Indian tribes and dealt with them by treaty, Congress[,] by Act of March 3, 1871, prohibited the further recognition of Indian tribes as independent nations. Thereafter the Indians and the Indian tribes were regulated by acts of Congress. The power of Congress to govern by statute rather than treaty has been sustained. United States v. Kagama (1886). That power is a plenary power (Matter of Heff (1905)) and[,] in its exercise[,] Congress is supreme. United States v. Nice (1916). [citations omitted]

In relating to tribal governments, the federal government acts under authority of provisions of the Constitution. In Article I, Section 8, the Constitution states: The Congress shall have power... to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the several states, and with Indian tribes. Moreover, treaties, agreements made with the Indian tribes, are part of our nations supreme law in furtherance of the federal governments powers with respect to dealing with Indian commerce. Article VI of the Constitution notes: This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made... shall be the supreme law of the land....