Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260

Copyright 2019, University of Pittsburgh Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 13: 978-0-8229-6574-9

ISBN 10: 0-8229-6574-7

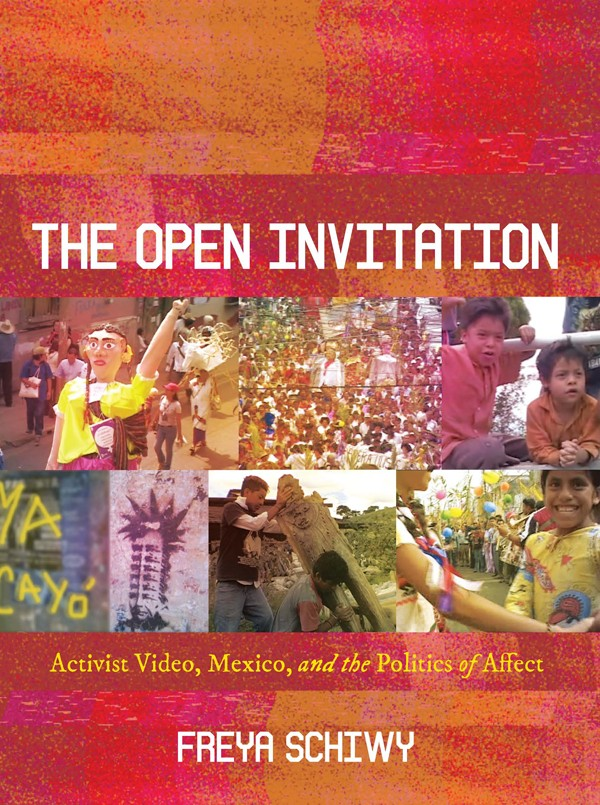

Cover design: Melissa Dias-Mandoly

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-8667-6 (electronic)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book grew from a double spark. In 2008, two years after his trip to Oaxaca, Daniel Nemser, who then was still a graduate student at UC Berkeley, gave a formidable presentation at UC Santa Barbara on how various artists and activists deployed old and new media during what many came to call la comuna de Oaxaca (the Oaxaca Commune). I am grateful to Daniel and the other members of the multidisciplinary research group Subaltern and the Popular who, over several years while funding for yearly meetings was still forthcoming, nurtured the seeds of this project with their intellectual effervescence, generosity, and good humor. Debating across geographies and different postcolonial histories about the limits, entrapments, and potentialities of what we called subaltern and popular practices, the group provided the kind of open-ended stimulus and opportunity for exchange of ideas and reflections that I have always found to be one of the most exciting and rewarding aspects of academic work.

At the same time, as I began incorporating the audiovisual works of young video makers from the Zapatista base communities into my classes about militant filmmaking and decolonization at UCR, I noticed my students ending the quarter with a new sense of optimism. The powerful revolutionary films from the 1960s and 1970s produced for them not rage but rather disaffection or sadness, at best aesthetic pleasure in experimental form. When we discussed Un tren muy grande que se llama La Otra Campaa (A Very Big Train Called the Other Campaign) in one of my graduate classes, in contrast, several students claimed that the video made them feel strongly moved to act. They emphasized that Un tren counters the negative image of the Zapatistas and the Other Campaign disseminated by Univisin in the United States and that they themselves felt the desire to extend this kind of grassroots democracy, exterior to the state and its institutions, on our side of the border. The experience repeated itself even more forcefully when I began including videos from Oaxaca and the Yucatn. Many of these videos thrive on humor and optimismeven in the face of repressionand their effect has been contagious. I thank the remarkable undergraduate and graduate students at UCR who have taken my classes for their intellectual curiosity, enthusiasm, and for allowing me to learn from and with them. Teaching at UCR has been a unique and often humbling experience.

Like any research that engages with media activism, this project was only possible because some of those involved with collaborative and community video art and activism generously shared their thoughts, their time, and their creative work. In 2009, Bryt Wammack Weber, Ana Rosa Duarte Duarte, Alexandra Halkin, and I formed a panel at the Hispanic Cinema conference at Tulane. For me this was an important first opportunity to reflect collectively on video and the political in the context of southern Mexico. Our collaboration broadened and eventually resulted in the publication of Adjusting the Lens. I am deeply indebted to the contributors and all those who along the way helped me think through the issues of collaborative and community media in transnational Mexico: Byrt Wammack Weber, Ana Rosa Duarte Duarte, Alex Halkin, Laurel C. Smith, Ingrid Kummels, Liv Stone, Argelia Hurtado Gonzlez, Elas Levn Barn Rojo, Gabriela Zamorano Villareal, Erika Cusi Wortham, Jesse Lerner, David Wood, and Claudia Magallanes Blanco. I have learned so much from their work about collaborative video in indigenous languages in Mexico and Los Angeles and many of them have become dear friends.

Although I wish my field research in Oaxaca in 2010 (made possible by a University of California Regents Faculty Fellowship) could have been longer than three months, I am grateful to Roberto Olivares from Ojo de Agua Comunicacin for meeting with me and sharing his time, insights, and his work, including his powerful documentary Compromiso cumplido. This collaborative media center generously gave me access to DVD copies of Mal de Ojo TV videos, many of which are at the center of this book. Gustavo Esteva at that time was conducting a seminar about Zapatismo at the Universidad de la Tierra in Oaxaca. He generously let me sit in on his lectures, seminar discussions, and other meetings at Unitierra, as well as take part in an overnight field trip to a Zapotec community. Gustavo Esteva also facilitated contact with Sergio Beltrn, Oliver Frhling, and Jaime Martnez Luna. DVD vendors in the streets of Oaxaca shared their thoughts on the uprising and its afterlife on DVD and online.

Ingrid Kummels was instrumental in introducing me to the talented Carlos Prez Rojas and bringing him to screen and discuss his films at UCR. Thank you also to Yolanda Cruz for coming out to Rside and sharing her brilliant work with myself and my students. I am deeply thankful to Byrt Wammack Weber and Ana Rosa Duarte Duarte in Mrida for their friendship, for teaching me about video art and activism from the Yucatn perspective, and for generously sharing copies of a selection of Turixs amazing video shorts, two of which I discuss in this book. In 2011, their invitation to participate in the Encuentro Internacional (International Meeting) Translocaciones/Saberes Hbridos in Mrida offered me the opportunity to discuss the ideas in . Davids thoughtful commentary drew my attention to the question of how the sense of cinema and temporality may be changing with the almost unlimited ability to record in digital formats. It is a topic that deserves more attention than I was ultimately able to give it here.

Horacio Legrs invited me on several occasions to present my evolving work on this book, both to conference audiences and to his graduate seminar at the University of California, Irvine. Erin Graff-Zevin and Julian Daniel Gutirrez Albilla extended friendship and an invitation to share my work at USC. Ricardo Wilson resourcefully and with persistence found the composers and performers of one of the songs (Aguadiosa) in Compromiso cumplido. Laura Podalsky invited me to discuss my incipient work on the politics of affect with her and her colleagues in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Ohio State University; Gabriela Copertari at Case Western Reserve University and Luis Dunno-Gottberg at Rice University generously commented on my work in progress and provided opportunities for feedback from broader audiences and for meeting with old and new friends. Erika Suderberg and Ming-Yuen S. Ma first published my reflections on the intersection of political thought in indigenous video and Rancires writings. Later on, they invited me to share this chapter at a celebration of their edited volume Resolutions 3 at Pitzer College. At this event I finally met Jesse Lerner who opened my eyes to video art and the punk movement in Mexico, allowing me to hear Byrt when he insisted that community video in indigenous languages is rooted not only in the Mexican states Media Technology Transfer Program but also, and perhaps even more so, in the irreverent Super 8 and video art and activism movements independent of the state.