Published by Otago University Press

Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street,

Dunedin, New Zealand

Fax: 64 3 479 8385.

Email:

First published 2011

Copyright Erik Olssen and Clyde Griffen 2011

ISBN 978 1 877372 64 3 (print)

ISBN 978 1 927322 56 7 (EPUB)

ISBN 978 1 927322 57 4 (Kindle)

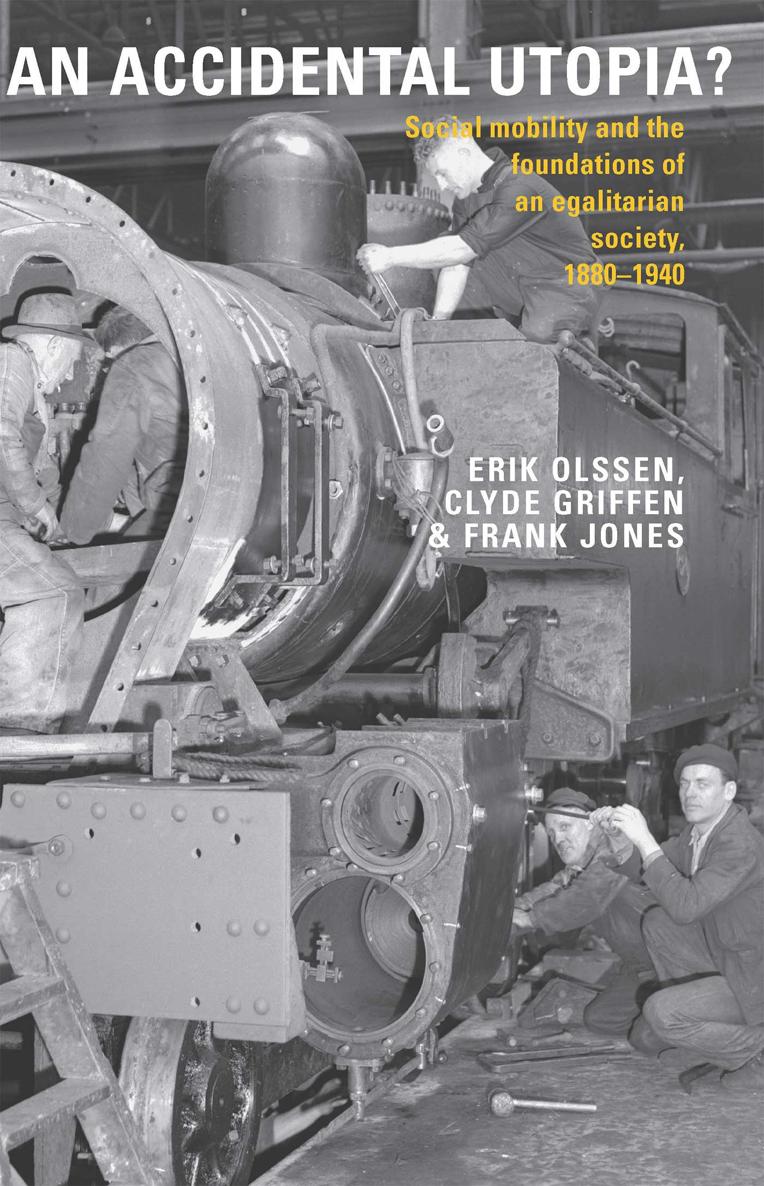

Front cover: Workers building a locomotive at the Hillside Railway Workshops, c. 1900.

Hocken Collections

Back cover: Southern Dunedin resident and Olympic gold medal winner Yvette Williams

practising her long jump technique at St Clair beach in about 1950.

Evening Star photo, Otago Daily Times/Allied Press

Ebook conversion 2015 by meBooks

List of Tables and Figures

Tables

Page

.

In Appendix

Figures

Page

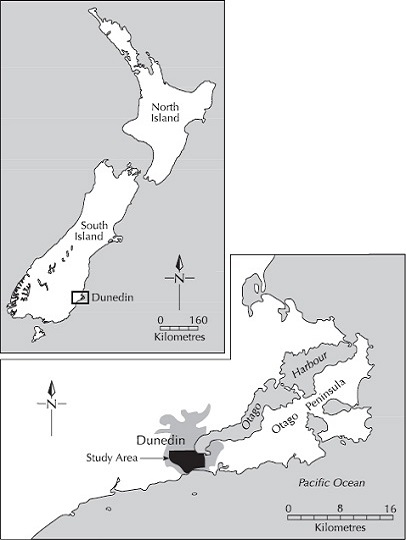

Figure 1.1 New Zealand, the city of Dunedin, and the study area of southern Dunedin.

The Caversham Project

This history research project began in 1975 as an endeavour to identify the main social structures and principal changes that had occurred in urban New Zealand by using systematic methods and comparative analysis. The aim was to reconstruct the population of a local area, initially Dunedins old Borough of Caversham, in the early twentieth century and introduce the new social history to the study of New Zealands past. We chose this locality because it was the countrys earliest industrial suburb.

In 1994, the first review of the History Department at the University of Otago recommended that the Projects Principal Investigator, Erik Olssen, apply to the Foundation for Science, Research and Technology for adequate funding (hitherto the Project had survived on the smell of a greasy rag and the goodwill of a few students). The first application Urban Society and the Opportunity Structure was to study worklife occupational mobility, transience, and residential segregation in Caversham from 1902 until 1919. It succeeded and provided funding for 1995 to 1998. In 1998, having identified gender as a major issue, the Project sought funding for a further period. Although we did not get all we wanted, this phase Space, Time, Gender and the Opportunity Structure received funding which continued until 2002. In 2002, we failed in our attempt to obtain funding to extend the time period for the Project as a whole.

Two further developments warrant explanation here. First, in 199899 we used optical scanning techniques to greatly extend our first database, derived from electoral rolls, to cover the three southern boroughs and not just Caversham, and extended our period of coverage from 190219 to 18931938. Second, we constructed a second database derived from marriage registers held by thirteen churches in the study area, across the period 18801940. The major changes of interest to the Project occurred in that latter period but for various reasons explained later our electoral roll database starts in 1902. This book is largely based on those two databases.

A brief sketch of the Project, listing all working papers (some available as pdf files), theses and publications, and access to the main databases can be found at its website: http://caversham.otago.ac.nz.

During the life of the Caversham Project, a large amount of material was generated, out of which four books and a great many academic papers have been produced. The archives, including all research reports, oral-history transcripts, working papers, documentary sources and relevant essays done by students, have been deposited in the archives of the Hocken Collections at the University of Otago as Ms2690.

Preface

This volume, the fourth to be produced by the Caversham Project, brings together the results of our work on social mobility (ironically our first objective some thirty-five years ago). Since then, many people have worked on this attempt to determine whether the ease with which men could achieve upwards social mobility rendered class irrelevant in explaining change between c. 1880 and 1940, the critical period in the shaping of modern New Zealand. W.H. (Bill) Oliver, who became a close friend and colleague on several projects, once claimed in a famous essay that this was in fact the case, thus prompting Erik Olssens scholarly wrath, and then this project. Tom Brooking and Barbara Brookes, both now professors, played particularly important roles for lengthy periods of time. In 1994, Clyde Griffen, now Emeritus Professor at Vassar College, joined the team. His knowledge of and interest in social mobility has helped to ensure that this project finally achieved its first goal.

Like the other collaborations central to this project, this one was born of our shared passion for social history and has been nurtured by our mutual enthusiasm for pursuing the argument wherever it led. Our collaboration began, in one sense, when we first read each others work and felt a commonality of purpose. It became more likely, although neither of us then anticipated this collaboration, when the History Department at the University of Auckland used the Fulbright programme to seek an expert in what was then widely known as the new social history, to find and survey local sources relevant to such a project in Auckland. The Griffens did just that (for Sally, too, was an historian, although she then worked as a university administrator). In the process they both became interested in New Zealand, and Clyde began reading widely in New Zealand history. We met then but only briefly, although Clyde was very enthusiastic about the embryonic Caversham Project. That project was under-capitalised for its first twenty years. When applying in 1994 to the Foundation for Research, Science and Technology (FoRST) for adequate funding, Erik was told that an international collaboration might strengthen the projects prospects. Given his long-standing interest in the history of the United States he did his PhD at Duke University in the 1960s and that prompted him to ask the questions central to the new social history of New Zealand he immediately asked Clyde whether he would be interested in joining the research team. Clydes response was positive and so the comparative focus for this study of class and mobility became possible.

Erik conceived the project, obtained the resources, created two research teams and supervised a staff that varied from three to around ten research assistants. He did his best to manage everything, but often lacked the time to stay abreast of the complex literatures relevant to the projects purposes. The New Zealand university, strapped for cash and driven by bums on seats, was scarcely a research-friendly institution in the 1990s. Niggardly governments forced universities to devour what they purported to nourish. Clydes knowledge of occupational mobility and urban history more generally, not to mention the history of gender in modern America, together with his generosity of spirit and contagious energy, would have been invaluable anyway. Because of the peculiar situation in New Zealand, those contributions have proven even more valuable. His prompt and full responses to drafts, queries, and ideas, not to mention his willingness to settle down with pencil and paper to calculate innumerable means and medians, injected a relentless stream of disciplined enthusiasm and energy into the project. A fat file of faxes reminds us still that we have enjoyed and benefited from our collaboration.