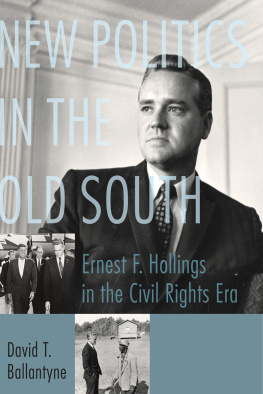

New Politics in the Old South

New Politics in the Old South

Ernest F. Hollings in the Civil Rights Era

David T. Ballantyne

THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA PRESS

2016 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

ISBN 978-1-61117-703-9 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-61117-704-6 (ebook)

Front cover photographs: Governor Hollings, 1960, (bottom inset) Senator Hollings during his 1969 hunger tour, and (left inset) Sen. John F. Kennedy, Sen. Olin Johnson, and Governor Hollings at the Columbia airport during Kennedys 1960 presidential campaign, courtesy of the Hollings Collection, South Carolina Political Collections, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

For Kate

Contents

CHAPTER 1

From Charleston to Columbia

CHAPTER 2

Segregation with Dignity?

CHAPTER 3

Hollings, the Kennedys, and Democratic Decline in South Carolina

CHAPTER 4

Backlash

CHAPTER 5

Hunger, USA

CHAPTER 6

A common-sense, realistic, South Carolina Democrat

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to countless individuals and organizations who helped me during the course of this project. Tony Badgers patience and expertise greatly improved the quality of my work. Adam Fairclough, too, has been extremely generous with his time in offering me advice on research, teaching, and academic employment. I am also grateful to the conveners and participants of the American History Graduate Workshop at the University of Cambridge who reviewed preliminary versions of several chapter drafts. I owe thanks as well to the editorial staff at the University of South Carolina Press, especially Alex Moore, Linda Fogle, and Bill Adams, for their repeated assistance in bringing this project to fruition.

I have been fortunate to receive extraordinary levels of assistance from many archivists and librarians at the Hollings and South Caroliniana Libraries at the University of South Carolina, the Citadel Archives, the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, the South Carolina State Library, the U.S. Senate Historical Office, and the Johnson and Nixon Presidential Libraries. Patrick Scott, alongside the staff from the Hollings and South Caroliniana Libraries, made me feel welcome in Columbia throughout my stay there. In particular I must thank Herb Hartsook, who graciously responded to my constant questioning and put me in touch with many of the people I later interviewed.

My thanks go to Bob Ellis from the University of South Carolinas Institute for Southern Studies for his encouragement and assistance throughout my work in the state. The visiting fellowship provided by the institute enabled my prolonged study in South Carolina during the 201112 academic year. I am also the recipient of a Richard A. Baker Graduate Student Research Travel Grant from the Association of Centers for the Study of Congress and several funding grants from the Cambridge History Trust Funds and Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.

For the images reproduced in this book, my thanks go to the Hollings Librarys Kate Moore, Heather Moore of the U.S. Senate Historical Office, and Bill Barley. I am also indebted to the interviewees and correspondents themselves. Their willingness to engage with me added significantly to my understanding of the topic and the richness of my research. Beyond those cited in the endnotes, I am grateful to John Mark Dean and Joe Riley for talking with me; and Michael Hollings, Hayes Mizell, and Nic Butler, who kindly corresponded with me about my project. Various historians, including Jim Cobb, Walter Edgar, David Farber, Philip Grose, Laura Kalman, Felicia Kornbluh, Thomas Lekan, Don Ritchie, Ellie Shermer, Bryant Simon, Pat Sullivan, and Kerry Taylor, took the time to discuss my work with me. Their suggestions have much improved this book.

Without the repeated encouragement and support of my whole family, especially my parents, this project would not have been possible. Finally I must thank my wife, Kate, whose proofreading, emotional support, and endless tolerance for all things South Carolinarelated made my research vastly more manageable and enjoyable than it otherwise could have been.

Introduction

E rnest F. Fritz Hollings was a key figure in South Carolina and national political developments in the second half of the twentieth century. He was arguably the states most influential Democrat in that period, serving more than fifty years in elective politics. By the time he retired in 2005, he was also the last Democrat to hold high-level statewide office in South Carolina, a remarkable turnaround in the partisan landscape of the formerly one-party Democratic state. First elected as a state representative from Charleston in 1948, Hollings won the states governorship in 1958 and a U.S. Senate seat in 1966, which he held until his retirement thirty-eight years later. Having served alongside the party-switching Republican Strom Thurmond for thirty-six years, Hollings was the longest-serving junior senator in U.S. history.

Throughout his career Hollings was renowned for his willingness to voice what he perceived to be unpleasant truths. According to John West, who was elected governor himself in 1970, Hollingss closing speech to the General Assembly as governor in January 1963, in which he urged legislators to accept the desegregation of Clemson College peacefully, simply deflated the strong, prosegregation sentiment in the state. A racial moderate by South Carolina standards in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Hollings influenced his state in its grudging but peaceful move away from total defiance of the Supreme Courts Brown v. Board of Education ruling. When the national Democratic Party forthrightly embraced civil rights concerns, Hollings remained a Democrat, unlike Thurmond, and made a gradual but tangible shift away from segregationist politics in the late 1960s. By the early 1970s, he had embraced a degree of racial moderation. In contrast older southern Democrats such as Georgia senator Richard Russell or North Carolinas Sam Ervin continued to reject the legitimacy of black political participation and civil rights advances.

Known as the bull-headed Dutchman while studying at the Citadel, Hollings was renowned as an energetic and confident, sometimes abrasive, politician with an acid wit.

Hollings as a cadet at the Citadel

Hollings as a cadet at the Citadel.

SOURCE: South Carolina Political Collections, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Despite the occasionally blustery exterior, Hollings was a policy-oriented politician. From his championing as a state legislator of a sales tax to improve school facilities to his promotion of a technical training program as governor and his advocacy as a U.S. senator for expanded federal antihunger programs and ocean preservation measures, Hollings was concerned to make substantive policy gains. Vice President Joe Biden was sufficiently impressed by his Senate desk partner of thirty-two years that he proclaimed during a speech in 2010 that Hollings had contributed more over the course of his life to the state of South Carolina than any man in all of political history in this state.

Hollings as a cadet at the Citadel.

Hollings as a cadet at the Citadel.