Copyright 1985 by Lynn 1. Perrigo

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

First Edition

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data:

Perrigo, Lynn I., 1903

Hispanos: historic leaders in New Mexico.

Includes index.

1. Hispanic Americans-New Mexico-Biography. 2. New

Mexico-Biography. I. Title.

F805.S75P47 1985 978.900468 [B] 85-489

ISBN: 0-86534-011-0

ISBN: 9-78161139-900-4 (e book)

Published in 1985 by SUNSTONE PRESS

Post Office Box 2321

Santa Fe, NM 87504-2321 / USA

PREFACE

The evolution of New Mexico has been well described in several state and regional histories. In them, after the Spanish and Mexican periods, the emphasis is upon the westernizing process, that is, the flurry of activity by newcomers in the transformation that occurred as the area was being developed into an integral part of the United States.

The purpose of this book is to present a sampling of the careers of eminent Hispanos so that an appraisal of that part of the story can be made more readily. When done, it is noteworthy that much of the history of New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment, is interwoven in the experiences of the several subjects.

A bibliography of all sources drawn upon for detail and background would fill much space. Nevertheless, I am obligated at least to give credit to a few works, each of which provided information about several of the individuals. They are Gilberto Espinosa and Tibo V. Chvez, El Ro Abajo, edited by Carter M. Waid; Ralph Emerson Twitchell, The Leading Facts of New Mexico History; Maurilio E. Vigil, Los Patrones: Profiles of Hispanic Political Leaders in New Mexico; Nancy Benson, Notable Women of New Mexico; State Planning Office, The Historic Preservation Program in New Mexico, Volume II; and various works by Fray Anglico Chvez and Father Stanley Crocchiola. In addition, I must admit that I have condensed some passages from one of my books, The American Southwest.

To three specialists in this field, now associated with New Mexico Highlands University, I am indebted for their critical reading of the manuscript and their appraisal of its contents. They are Dr. Guillermo Lux, Professor of History; Dr. Maurilio E. Vigil, Professor of Political Science, and Dr. John A. Aragn, President.

In addition, Arthur Olivas, Photographic Archivist, Museum of New Mexico, Lane Ittleson, Deputy Historic Preservation Officer, and Richard Salazar, Deputy Director, State Records Center, lent assistance with the procurement of photographs for illustrations.

Although the term Hispanos has come into widespread use only recently, it has been employed in the title because it is current and comprehensive. Through much of the time encompassed by this series of profiles, Anglos commonly referred to the Spanish-speaking people as Spanish Americans and Mexicans, whereas the latter usually called themselves Neo-Mejicanos and Hispano-Americanos. In this work, therefore, Hispanos and Spanish Americans are used interchangeably. The term Mexican Americans generally has been inapplicable throughout the history of this state, because there have been but few recent migrants having a heritage of rural Mexican folk culture. There is one in this series of biographical sketches who might then have been so regarded, because he was born in Mexico; but, as will be seen later, he soon became a close affiliate of the people descended from pioneers having a more direct Spanish heritage.

As a rule, whenever there is an appropriate noun, as, Hispanos, the adjective, Hispanics, need not be employed as a noun. However, early in the course of popularization of that term, writers for the media introduced the improper usage, and others have repeated it until it has become commonplace. That does not justify a deviation from the preferable practice in the title and context of this formal study.

Lynn I. Perrigo

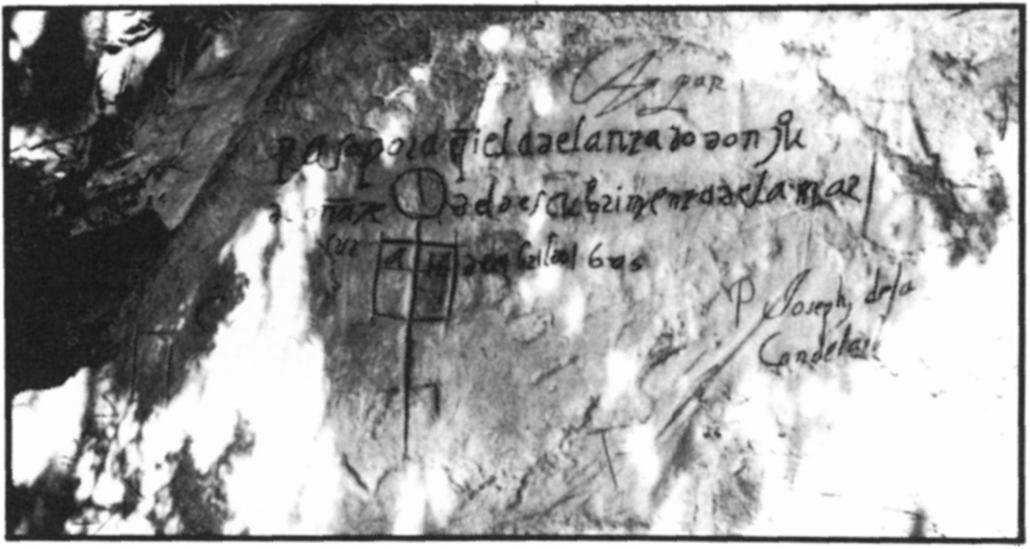

While Juan de Oate was traveling afar in his futile quest of a great discovery, he had the above inscription engraved at El Morro (Museum of New Mexico).

I

First on the Frontier

After Spanish exploration of the northern frontier of New Spain between 1528 and 1541 a recess of over half of a century followed, and there was a reason for it. A search for wealth was the main motive of that era, and no great riches had been found.

In succeeding years Spaniards became inspired by new motives. For one, in 1542 a debate between Franciscan friars and would-be conquerors was settled by a royal decree in support of the contention of the friars that the Indians in America were human beings who had souls to be saved instead of something akin to animals subject to enslavement. That introduced two new motives conversion and the colonization necessary to effect it and to develop the frontier. Then, as more time passed, the opening of silver mines north of Mexico City and wars with Indians pushed the frontier northward into Chihuahua, where a shorter route was found to New Mexico, up the Ro Grande instead of over the mountains from western Mexico and thence across what now is Arizona. This revived interest in the land of The Seven Cities.

In that era the Crown let contracts to the highest bidder, that is, to the nobleman who had a favorable ancestral record and who offered to put the most resources into a colonizing expedition. In 1595 Juan de Oate won the contract for colonizing New Mexico. His father, who had come to New Spain in 1541, was a veteran of the Indian wars who had acquired wealth from mining. Moreover, Oate was a personal friend of the viceroy, and his wife had a dowry as a descendant of Hernando Crtez, the conqueror of Mexico City.