Copyright 2019 by The University of Arkansas Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN: 9781-682261026

eISBN: 9781-610756723

23 22 21 20 19 5 4 3 2 1

Designer: April Leidig

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Johnson, Ben F., 1953 author.

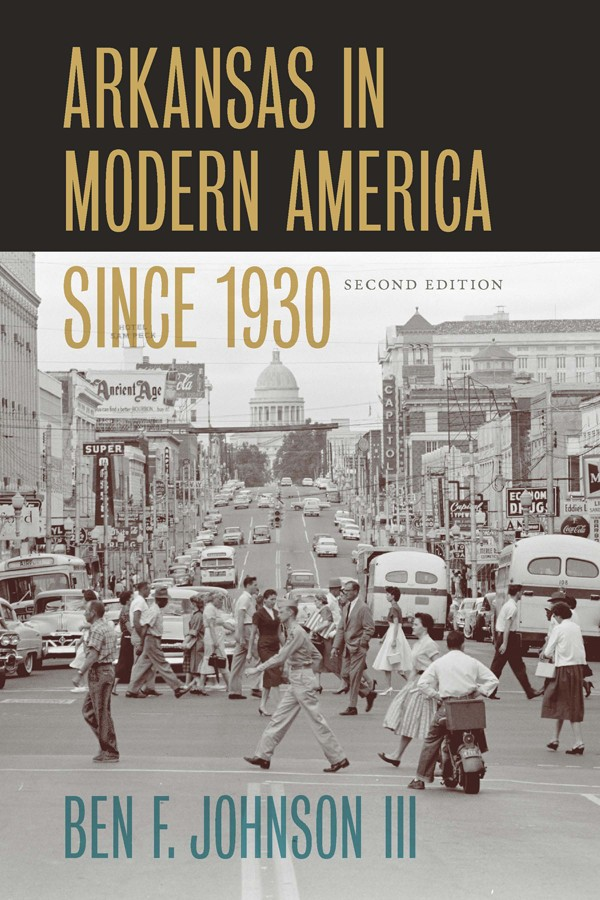

Title: Arkansas in modern America since 1930 / Ben F. Johnson III.

Description: 2nd edition. | Fayetteville : The University of Arkansas Press, [2019] | Includes index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019000981 (print) | LCCN 2019002838 (ebook) | ISBN 9781610756723 (electronic) | ISBN 9781682261026 | ISBN 9781682261026 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781610756723 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: ArkansasHistory1865

Classification: LCC F411 (ebook) | LCC F411 .J64 2019 (print) | DDC 976.7/05dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019000981

Acknowledgments

Neither the first nor the second editions of this book would have been completed without the generous help and advice from friends and colleagues.

Bettie H. Mahony skillfully edited the initial drafts of the manuscript for both the first and second editions.

Those who offered critical revisions and insightful suggestions for the first edition include Elliott West, Ernest Dumas, Willard Gatewood, Roy Reed, Martha Rimmer, Bill R. Wilson, and Bill Worthen. Robert Brown and Rex Nelson kindly took time to answer my questions about recent developments in the course of preparing this edition.

Those who provided invaluable advice and suggested revisions for the final section of the second edition include Fred Harrison, Uvalde Lindsey, Emon Mahony, Joe David Rice, Bobby Roberts, and Bill R. Wilson. I am also grateful for the comments from the University of Arkansas Presss anonymous reviewers.

These readers deserve credit for the books strengths, but I must answer for its faults.

I am also in the debt to those who provided suggestions, documents, and favors in the course of my research for either the first or second editions: Charles Bolton, Michael Dabrishus, Holly Hope, Alan Hughes, Steve Jones, Greg Kiser, Carl Moneyhon, Michael Pierce, Linda Pine, Travis Ratermann, Stephen Recken, Wendy Richter, Scott Simon, Keith Sutton, Ed Swaim, Curtis Sykes, Donald Tatman, Becky Thompson, Charles Venus, Ralph Wilcox, Patrick Williams, Steve Wilson, Susan Young, Lee Zachery.

I am profoundly grateful for the assistance of the staff at Special Collections, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, the staff at Archives and Special Collections, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and the staff of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. At the Magale Library, Southern Arkansas University, Margo Pierson navigated me to relevant sources while Donna McCloy patiently responded to my requests for interlibrary loan materials. I also owe considerable thanks to my former colleagues at the South Arkansas Community College Library: Phillip Arndt, Joyce Adams, and Ellen McGowan. My current colleagues in the Department of History, Political Science, and Geography at Southern Arkansas University have my deepest appreciation for their collegiality and friendship.

The editors and staff of the University of Arkansas Press have been patient beyond all reasonable measure over the prolonged life of this project.

I received support from the Southern Arkansas University Research Fund, and I am indebted to the generosity of John G. Ragsdale Jr., who has contributed in countless ways to the study and awareness of Arkansas history.

Over the course of many years, Jodie Mahony explained to me how things were done in Arkansas, and his influence permeates this book. Out of my family of long-standing Texans, my cousin Ethel Johnson Wood and I had the good fortune to marry Arkansans. Beyond offering gracious encouragement, Sherrel kept the book on track through incisive editing and ideas that cleared narrative roadblocks.

INTRODUCTION

ARKANSAS BETWEEN THE grim years of the Great Depression and the advent of a new century moved by fits and starts to become a modern American state. The states traditional economy and society gave way slowly, and vestiges remained even with the states integration into the nation.

This edition, like the first published in 2000, is a narrative overview of recent Arkansas history incorporating a range of topics rather than offering a focused argument underpinned by footnotes. A number of themes developed in the previous edition persist in this volume. State politicians, federal officials, and business leaders formed shifting, sometimes uneasy coalitions centered on the assumption that economic modernization required expanded government services untainted by favoritism and graft. The outflow of population from rural sections eroded political localism and gave reformers the opening to build upon federal policies to uproot voter disfranchisement and fraud. The long struggle for racial justice continued after the downfall of official and overt segregation to confront less conspicuous but formidable barriers to opportunity and equity. Observances of the 1957 Little Rock Central High desegregation crisis increasingly became civic debates over whether reconciliation masked enduring burdens weighing on African Americans in the new century.

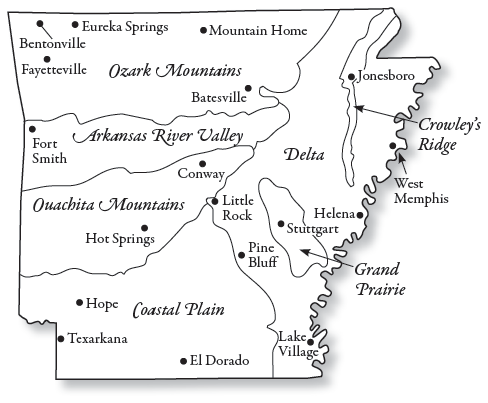

Even as the daily experiences of Arkansans more closely resembled those of other Americans, writers and promoters of regional folkways cultivated a distinct state identity that echoed a rustic past. Premodern customs that Arkansas boosters and defenders had once derided as backward and stereotypical were respectfully studied and slated for preservation. The Ozark region became the seedbed of Arkansas cultural attributes as well as the location for a line of urban centers that challenged Little Rocks traditional preeminence in the state. Corporations with a global reach underwrote the prosperity of the northwest corner and sharpened the contrast between struggling rural communities and expanding cities.

The Arkansas that Bill Clinton left to begin his presidency in 1993 was far different than the postWorld War II state into which he was born. He likely would not have reached the White House if governing a state in which the corrupt politics and narrow economy of that older era had endured. Yet agricultural interests and natural-resource industries retained a greater influence and more economic heft than elsewhere. Small communities withered, sometimes leaving behind only a name on a roadside sign at the edge of a pine plantation. Neighbors were more likely to see one another on weekends at a favorite catfish buffet or barbecue joint than a town square or local hardware store. Arkansas, however, still ranked as one of the most rural in the nation and trailed only Mississippi among the former Confederate states in percentage of residents not living in towns.

The essay on sources at the end of this volume demonstrates the substantial and worthwhile scholarship that has been published since the original edition. The contributions of these works allowed me to fill in gaps and reconsider conclusions. Few historians have a second chance to set matters straight and clear up mistakes. Not wishing to squander the privilege, I set out to rewrite the volume rather than merely update the material. While all sections have been substantially revised, the final one here bears little resemblance to its counterpart in the earlier book. I remain hopeful that the shortcomings and omissions in this edition will inspire others to correct and elaborate.