Controlling the Message

Controlling the Message

New Media in American Political Campaigns

Edited by Victoria A. Farrar-Myers and Justin S. Vaughn

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2015 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN: 978-1-4798-8635-7 (hardback)

ISBN: 978-1-4798-6759-2 (paper)

e-ISBN: 978-1-4798-6550-5

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Contents

Victoria A. Farrar-Myers and Justin S. Vaughn

Daniel Kreiss and Creighton Welch

Girish J. Gulati and Christine B. Williams

Julia R. Azari and Benjamin A. Stewart

Robert J. Klotz

Regina G. Lawrence

Mike Gruszczynski

Matthew Eshbaugh-Soha

Joshua Hawthorne and Benjamin R. Warner

Meredith Conroy, Jessica T. Feezell, and Mario Guerrero

Todd L. Belt

Karen S. Hoffman

Daniel J. Coffey, Michael Kohler, and Douglas M. Granger

Brian R. Calfano

Victoria A. Farrar-Myers and Justin S. Vaughn

The conversation that set the wheels in motion for this book occurred in the lobby of the Marriott Waterfront Hotel in Portland, Oregon, where we both were attending the Western Political Science Associations annual meeting. In the many months since, we have watched as the idea first discussed there turned into the volume you now hold in your hands (or, perhaps more relevant to the subject matter enclosed within, read on your laptop or tablet). Throughout the process, we have been gifted with the cooperation, wisdom, and patience of our chapter authors, the professionalism of the staff at NYU Press, and the insight of four anonymous reviewers. We are particularly indebted to Caelyn Cobb, whose ideas and guidance made this a much better book and whose enthusiasm renewed us throughout the process from proposal to publication.

Each of us would also like to give thanks to special people in our lives. Victoria thanks her husband, Jason; son, Kyle; and Anne Tego, whose collective love and constant devotion give her the inspiration to pursue her dreams. Justin thanks his wife, Elena, to whom he was engaged that same fortuitous Portland weekend, and the four dogs and two kitties who help make the Western Puggle Dome a place of love and joy.

Controlling the Message in the Social Media Marketplace of Ideas

VICTORIA A. FARRAR-MYERS AND JUSTIN S. VAUGHN

The presidential candidates campaign faced the threat of being derailed following a scathing depiction of him posted by an individual citizen. Regardless of whether the claims made against the candidate were truthful, the message already had gone viral, and the candidates campaign flailed in its efforts to respond. Finally, one of the candidates supporters not affiliated with his campaign repackaged the critics depiction into a new theme, one that resonated positively with voters. The repackaged message itself continued well beyond its original posting as it was replicated in different forums time and time again.

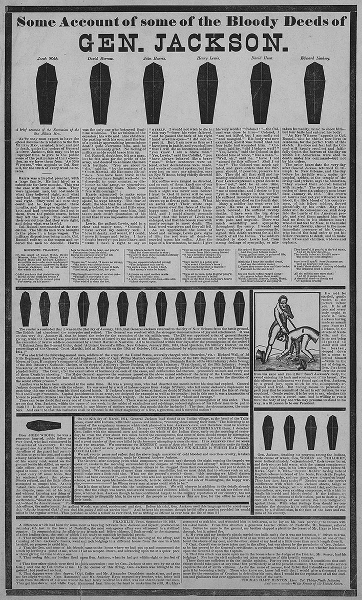

The presidential campaign from which this vignette was drawn was not the 2012 contest between former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney and incumbent President Barack Obama, where the use of social media was an indispensable tool in advancing positive narratives and beating back criticism. Nor was it the 2008 election, when Obamas first campaign for the presidency demonstrated the potential that the embryonic social media could have in the race for the White House (Germany 2009; Gulati 2010), or even in 2000, when Howard Dean demonstrated the effectiveness of the Internet as a fundraising tool (Kreiss 2012). Instead, the incident actually took place during the 1828 election between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson and involved the Coffin Handbill, a poster that depicted Jackson not as a military hero but instead as a murderer for his handling of six militia men whom Jackson ordered to be executed as their sentence for desertion (see ), and a subsequent newspaper editorial that recast the charges levied against Jackson in a positive light. Although the technology of printing presses and reliance on partisan-oriented newspapers may be antiquated in the world of modern political campaigns, the lesson behind this historical episode is timeless: candidates and their campaigns must worry about who controls the message affecting their campaigns.

Information, the Internet, and the 2012 Election

The volume of information produced and consumed in todays political world is immense. Furthermore, the outlets and mechanisms that producers of information use to provide, share, and communicate this information have proliferated as new and social media have become fully infused into daily political life and contemporary election campaigns (Howard 2006; Gainous and Wagner 2011). The low-cost use of the Internet has already and will continue to have a dramatic and likely long-lasting effect on American politics. In the battle waged in the marketplace of ideas for supremacy of ones viewpoint, an uploaded video that goes viral or a simple 140-character tweet can potentially be more effective than reliance on more traditional forms of communication. Moreover, the low barriers of entry into the marketplace of ideas resulting from the technological innovations of new and social media not only create a social media marketplace of ideas but also promiseor threaten, depending on ones perspectiveto make the nature of political discourse more democratic and less filtered. Indeed, we have reached the point where having a social media presence via a website, Facebook page, and Twitter account is a necessary means to be an effective political communicator. At the same time, however, merely having such a presence is hardly sufficient to ensure that ones message is reaching its intended audience, not being drowned outor, worse, distortedby competing messages.

Figure I.1. The Coffin Handbill (Courtesy of the Tennessee State Library and Archives)

Yet, despite all the focus on the use of new and social media in the political context, much of this phenomenon remains mysterious, if not misunderstood, by both practitioners and scholars of the political process. In order to realize the full power of new and social media in contemporary politics, one must first analyze and evaluate the implications that the corresponding free flow of ideas and information has for the American political system (see Farrell 2012; Dimitroval et al. 2014).

Such analysis and evaluation is the objective of this book. We utilize the context of the 2012 elections to study the phenomena of new and social media in American politics, with a particular focus on who controls the political message. For example, with this approach, one could examine the interaction between incumbency and using new and social media in the context of the 2012 presidential election. President Obama, as the incumbent, faced several structural advantages compared to Republican challenger Mitt Romney: no primary challengers, the ability to fundraise and spend resources solely with an eye toward the general election, and a longer lead time to dedicate to building campaign infrastructure. As a result, one would expect that Obamas campaign (and, more broadly, most incumbents) would develop more effective and innovative means to incorporate social media into the campaign as a means of controlling the campaigns message and reaching voters, as compared to the challenger. Obamas structural advantage should be kept in mind when evaluating the comparisons between the two presidential campaigns use of new and social media in this volume, but it also highlights the reason for choosing to study the use of such media in an electoral cycle. The 2012 election context offers a time when the amount of political discourse was naturally heightened, the number of participants involved in or at least paying active attention to the political process increased, and the perceived importance of the discourse and its impact on the future and course of the nation grew.