Copyright 2019

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036

www.brookings.edu

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press.

The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, education, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal purpose is to bring the highest quality independent research and analysis to bear on current and emerging policy problems. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Elgindy, Khaled.

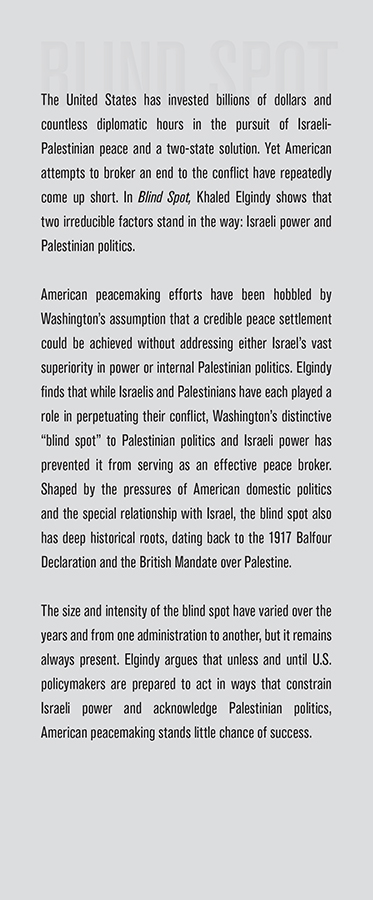

Title: Blind spot : America and the Palestinians from Balfour to Trump / Khaled Elgindy.

Description: Washington, DC : Brookings Institution Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019001459 (print) | LCCN 2019002843 (ebook) | ISBN 9780815731566 (ebook) | ISBN 9780815731559 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Arab-Israeli conflict. | Palestinian ArabsPolitics and government. | IsraelPolitics and government. | United StatesForeign relationsMiddle East. | Middle EastForeign relationsUnited States. | United StatesForeign relationsIsrael. | IsraelForeign relationsUnited States.

Classification: LCC DS119.6 (ebook) | LCC DS119.6 .E418 2019 (print) | DDC 956.04dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019001459

987654321

Typeset in Janson and Gira

Composition by Westchester Publishing Services

Preface and Acknowledgments

In July 2007, President George W. Bush declared that the United States would convene an international conference to relaunch long-stalled Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations. The announcement came as welcome news to Mahmoud Abbas, the affable if uncharismatic Palestinian leader. As one of the architects of the 1993 Oslo Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, or Oslo Accords, the secret agreement reached between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) that launched the current peace process, and the PLOs most ardent champion of negotiations, Abbas had been calling for the resumption of peace talks since he came to power in January 2005 following the death of Yasser Arafat, the longtime Palestinian leader. Like Arafat, Abbas headed both the PLO, the umbrella organization that represented Palestinians worldwide, and the Palestinian Authority (PA), the administrative body created by the Oslo Accords that governed Palestinians in the occupied territories. The PLO was the international political address of the Palestinian people, including some 5 million refugees displaced during Israels creation in 1948, while the PA represented the seedling of a future Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The proposed peace conference, which was eventually held in Annapolis, Maryland in November 2007, would be the first direct talks between the two sides since the eruption of the Palestinian uprising, known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada, some seven years earlier. The horrific violence, marked by waves of deadly suicide bombings by Palestinian militants and disproportionate and often indiscriminate attacks by the Israeli army, had claimed the lives of some 3,200 Palestinians and nearly 1,000 Israelis and left the bulk of the PAs security and governing institutions in shambles.

Bushs announcement was a clarifying moment for me as well. At the time I was serving as an adviser to the Palestinian leadership in Ramallah, the PAs de facto capital in the West Bank. As a member of a European-funded team of experts tasked with providing technical support to Palestinian negotiators, I had spent the previous three years preparing for precisely this moment. And yet most of us instinctively understood that the negotiations stood virtually no chance of producing a conflict-ending agreement between Israel and the Palestinians. Only a few weeks earlier, the Palestinian Islamist faction, Hamas, had routed and expelled the PAs security forces from the Gaza Strip, home to roughly 40 percent of the Palestinians in the occupied territories. In January 2006, Hamas had defeated Abbass Fatah party for control of the PAs parliament, the Palestinian Legislative Council, ending nearly four decades of Fatah dominance of Palestinian politics. The internal schism between the Fatah-dominated PA in the West Bank and the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip, which continues to this day, marked one of the lowest points in the history of the Palestinian national movement.

A few days after Bushs announcement, our team was summoned to the office of Saeb Erekat, the chief Palestinian negotiator and a close aide to Mahmoud Abbas, for a briefing on the proposed conference. At the conclusion of the briefing, I raised the question I knew was on everyones mind. With all due respect, I began, does Abu MazenAbbass traditional Arabic monikereven have a mandate to negotiate? Visibly annoyed, Erekat replied in the affirmative, assuring us that Hamass coup, as the leadership called it, had no bearing on the legitimacy of Abbas, who after all was still the elected president of the PA and chairman of the PLOs Executive Committee.

That Abbas and his Fatah party had just lost a civil war and a major election was even less of a problem for U.S. officialsto the contrary. The Bush administration had led the 2006 campaign to cut off the PAs international funding following the election of Hamas, a group that had carried out numerous attacks on Israeli civilians and was officially designated a foreign terrorist organization, and had previously insisted on Arafats replacement before peace talks could resume. While most ordinary Palestinians viewed the West BankGaza split as a setback to the national project, the Bush administration saw it as an opportunity to advance the peace process without the negative influences of Hamas, now ostensibly contained in Gaza by an international boycott and an Israeli blockade.

Events took a very different turn, however. After a highly elaborate yearlong negotiation process, the Annapolis talks collapsed when fighting broke out between Israel and Hamas in late December 2008. It was the first of several deadly Gaza wars in the decade that followed. In the meantime, Gazas continued isolation and the ongoing Palestinian division would remain an albatross around Abbass neck for the duration of his tenure, paralyzing internal Palestinian politics and repeatedly foiling peace negotiations.

The fact that U.S. officials saw a weak and increasingly dysfunctional Palestinian leadership as an asset to the peace process rather than a liability was striking in and of itself. More important, it was indicative of a systemic blind spot in Americas stewardship of the peace process in two critical areas of diplomacy: power and politics. Since the 1990s, American peacemaking in the Middle East has operated according to two interrelated and equally flawed assumptions: first, that a credible peace settlement could be achieved without addressing the vast imbalance of power between Israel and the Palestinians, and second, that it would be possible to ignore or bend internal Palestinian politics to the perceived needs of the peace process. The size of the blind spot has varied from one U.S. administration to another but has always been present.