2013 Georgetown University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Deep currents and rising tides: the Indian Ocean and international security / John

Garofano and Andrea J. Dew, editors.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-58901-967-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Indian Ocean--Strategic aspects. 2. Indian Ocean Region--Strategic aspects. 3. Security, International--Indian Ocean Region. 4. Geopolitics--Indian Ocean Region. I. Garofano, John, author, editor of compilation. II. Dew, Andrea J., author, editor of compilation.

DS341.D44 2013

355.03301824--dc23

2012037460

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

First printing

INTRODUCTION

JOHN GAROFANO AND ANDREA J. DEW

In the waning years of the twentieth century, pundits and policymakers alike argued that the new century would be a Pacific Century, one in which the rising economic powers around the Pacific Rim would dominate economic, military, information, and diplomatic spheres of power. In this new century the axis of influence in the world would shift to a new center of gravity centered on a far distant ocean: the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific Rim countriesfrom China and Japan in the north to the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) trading blocs in the south, from the western coastal states of the United States to Chile, Australia, and New Zealandso the argument went, would emerge from the shadow of the Atlantic Century, the twentieth century.

The argument in this book is that the security, economic, cultural, and diplomatic spheres of influence in the twenty-first century have indeed begun to shift from the northern Atlantic to far distant oceans, but not just to the Pacific. Rather, it is also to the Indian Ocean where we must turn our strategic attention. The Indian Ocean region has rapidly emerged as the geographic nexus of vital economic and security issues that have global consequences. As such, we argue, it is the Indian Ocean region that deserves urgent renewed strategic and diplomatic attention. Indeed, Robert Kaplan argues that the Indian Ocean is an environment in which the United States will have to keep the peace and help guard the global commonsinterdicting terrorists, pirates, and smugglers; providing humanitarian assistance; managing the competition between India and China. It will have to do so as a sea-based balancer lurking just over the horizon.

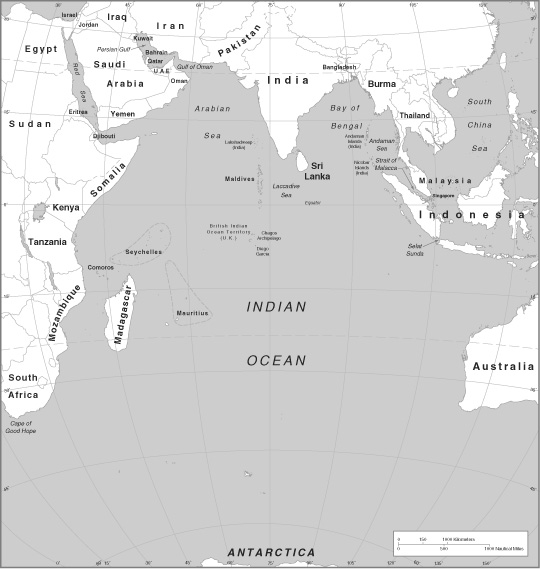

This raises the question, of course, of what exactly constitutes the Indian Ocean; where are its boundaries and what issuescompetition and cooperation must we understand in order to help guard the global maritime commons? The Indian subcontinent divides the Arabian Sea in the west and the Bay of Bengal in the east, and these regional seas are part of the Indian Ocean, the worlds second largest. The two subregions of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengaleach vast and, except for Oman and Yemen in the west, each densely populatedseparate the volatile mix of Arab politics and Islamic extremism in the west from the Confucian and Buddhist societies and booming economies of Southeast Asia in the east. India is the dominant geographic feature of the region, and the nation possesses several large island chains extending throughout the Indian Ocean.

As a global thoroughfare, the Indian Ocean is anchored by some of the most important geographic infrastructure and choke points on the planet. Traffic entering the Arabian Sea from the north must pass through two strategic choke points. From the Mediterranean, ships bound for the Indian Ocean must travel through the Suez Canal, Red Sea, Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, and Gulf of Aden; farther to the northeast, vessels may enter the Arabian Sea from the Persian Gulf via the Strait of Hormuz and Gulf of Oman.

From East Asia, vessels entering the Indian Ocean do so through the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, or farther south, through the Sunda or Lombok Straits. These key strategic straits are important for commercial and naval shipping, and the rules set forth in the international law of the sea control their use. Submarines, for example, are entitled to transit through straits while submerged, and warships can launch and recover aircraft during a strait transit, even in close proximity to the coastal state. Thus, the experience of state practice and sense of legal obligation that form customary international law, and the application of the codified international law of the sea pertaining to transit through straits used for international navigation, colors Indian Ocean security.

In the western Indian Ocean, abutted by East Africa and the Somali Basin, warlords rule the land and pirates roam the seas. An international coalition of naval forces has had mixed success in suppressing maritime piracy. The threat of piracy and the fractured nation of Somalia serve as a reminder that the problems in East Africa are greater than those of any of the continents five geographic regions. It is no wonder that only the Africa Bureau at the US Department of State has a security affairs component.

As John Martin, Clive Schofield, and Robin Warner discuss in chapters in this book, Somali piracy has also been a boon for the regions naval forces, and for developing new collective security mechanisms and legal measures to promote maritime security. India, for example, has been a leader in counterpiracy operations and in capacity-building in the region, since Indian dhows are frequent victims of Somali pirates. India is assisting Mauritius in installing shipborne sensors on Mauritius patrol ships and constructing coastal surveillance networks on shore. Delhi also helped the small island nation create a marine commando force to combat piracy. Seychelles and Comoros have also benefited from Indian support. Similarly, South Africa has expanded the mission set for the frigate SAS Mendi to conduct counterpiracy operations in the Mozambique Channel. The antipiracy mission is being used to improve interoperability with Mozambiques forces, and to advance maritime law enforcement training. Similarly, the SAS