THE REVOLUTION IN DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS

F OREWORD BY V ACLAV K LAUS

THE REVOLUTION IN DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS

EDITED BY J AMES A. D ORN, S TEVE H. H ANKE, AND A LAN A. W ALTERS

INSTITUTE

Washington, D.C.

Copyright 1998 by the Cato Institute.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The revolution in development economics / edited by James A. Dorn, Steve H. Hanke, and Alan A. Walters; foreword by Vaclav Klaus.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-882577-55-8. ISBN 1-882577-56-6

1. Development economics. 2. Economic development. 3. Free trade. 4. Central planning. I. Dorn, James A. II. Hanke, Steve H. III. Walters, A. A. (Alan Arthur), 1926

Printed in the United States of America.

C ATO I NSTITUTE

1000 Massachusetts Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

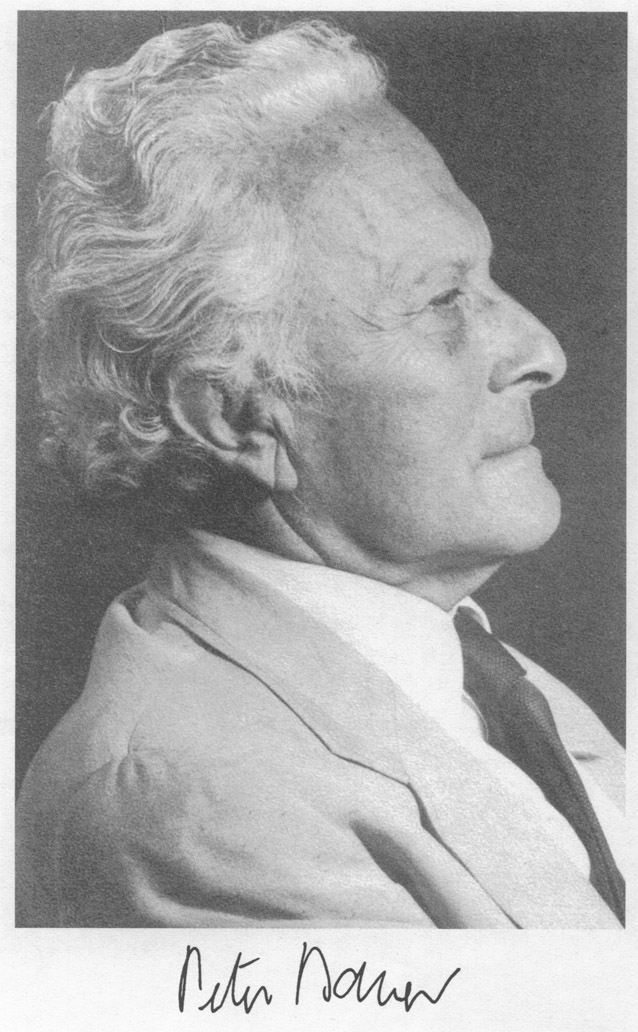

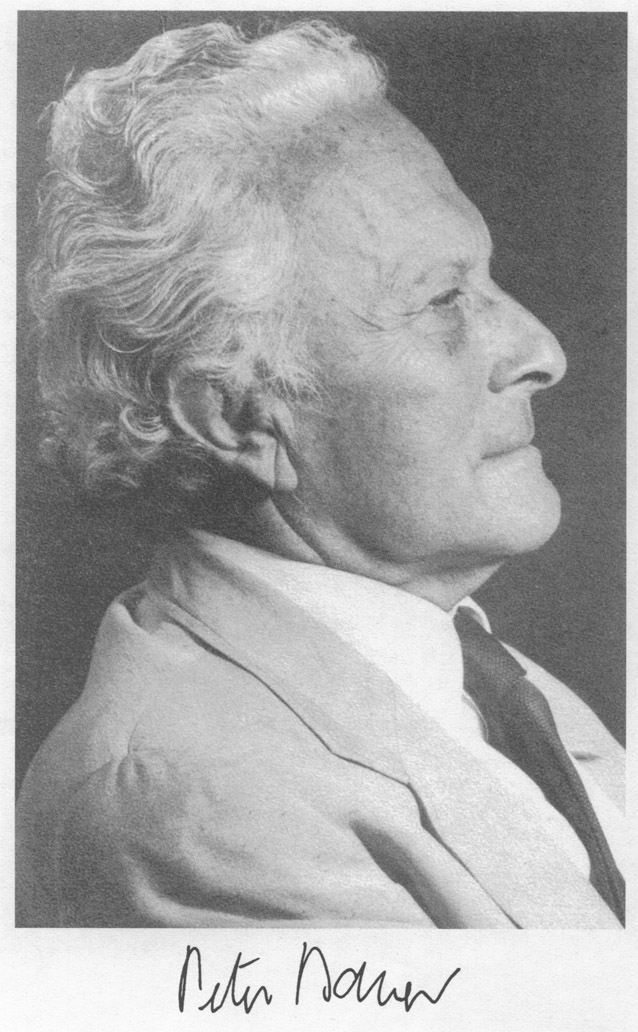

To Peter Bauer

F OREWORD

The Rise of Market Liberalism

Vclav Klaus

Human history and our own experience prove that social and economic progress spring both from the individual's efforts to do something positive and from his freedom to follow his own objectives and interests. They prove as well that human society is not an unorganized chaos of accidentally and unsystematically interacting individuals. We know that human society is based on a discipline and logic of existing social institutions.

Where those institutions emerge from the spontaneous activities of free individuals, they guarantee freedom and progress. Where they emerge from the power of government, they bring oppression rather than freedom, corruption rather than the rule of law, and decay rather than efficiency and equity. This general rule is valid for the whole world, for developed and developing countries, for arctic cold and equatorial heat, for mountains and lowlands, for all of us.

The free market is undoubtedly the most striking example of an institution of spontaneous order. It represents the precondition for freedom and prosperity. Social planning, on the other hand, though it proclaims devotion to the fulfillment of basic human values, actually undermines them. Communist regimes in Europe and their recent collapse give us the best evidence of that.

The citizens of former communist countries abandoned futile attempts to plan and started to change fundamentally their social, political, and economic systems-aiming at creating a free society, democracy, and a market economy. We are now witnessing an unprecedented transformation of those societies: a transformation of the formerly closed and undemocratic countries and their centrally planned economies into open, free societies with democratic govern ments and a market system, into societies with restored respect for the individual after decades of collectivism, into societies with renewed belief in the market after many decades of planning.

This revolutionary process has short-term costs that cannot be avoided. We especially cannot avoid or diminish them by stretching the process over a longer period, because that could create a danger of relying on malfunctioning old institutions without giving new institutions enough space and room to replace them. It was therefore necessary to organize major systemic changes immediately after the political change in our country. The crucial measures were based on radical liberalization of prices and rapid, massive privatization of state enterprises.

We did not hesitate, and experience shows that we were right. We succeeded in giving citizens a vision of prosperity based on liberalism and the free market. Most of them, in contrast to most Western "development experts," understand that we must rely on our own abilities and efforts, and that no foreign consultants and no foreign aid, however unselfish, can do the job for us and instead of us.

There have been few Western thinkers who understood all that and who preached such ideas in developing countries in the period of interventionism, statism, and social engineering. Many of them are represented in this book. We owe them much.

Note

The author is former Prime Minister of the Czech Republic.

1. IntroductionCompeting Visions of Development Policy

James A. Dorn

Economic achievement depends primarily on people's abilities and attitudes and also on their social and political institutions. Differences in these determinants or factors largely explain differences in levels of economic achievement and rates of material progress.

P.T. Bauer

Dissent on Development

Comprehensive Planning versus the Free Market

The love affair with comprehensive central planning ended with the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 and with the demise of the Soviet Union two years later. But long before the 1989 liberal revolution, it was clear that state-led development policy was doomed to failure. Economists such as Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, and Peter Bauer recognized the internal contradictions of trying to direct a complex economic system without the guidance of prices and profits and without well-defined private property rights protected by the rule of law.

Initial successes with Soviet-style central planning misled development experts into thinking that top-down systems of economic organization could correct for "market failures" and that input-output models could duplicate a competitive price system in allocating scarce resources. Conventional wisdom held that planners could better use existing information and achieve greater economic progress than could free individuals operating in a spontaneous market order.

A few examples will suffice to illustrate the faith placed in central planning during the heyday of state-led development policy in the immediate postwar era. In 1957, Stanford University economist Paul A. Baran wrote, "The establishment of a socialist planned economy is an essential, indeed indispensable, condition for the attainment of economic and social progress in underdeveloped countries" (Baran 1957, p. 261). One year earlier, Gunnar Myrdal had written, "The special advisers to underdeveloped countries who have taken the time and trouble to acquaint themselves with the problem ... all recommend central planning as the first condition of progress" (Myrdal1956, p. 201).

The planning mentality encompassed social engineering: the goal was not merely to control the economy but to control people and remake society. Myrdal's main thesis was, as Bauer (1976, p. 188) pointed out, that "personal conduct and social attitudes are to be restructured in the interest, or at least the declared interest, of higher per capita incomes." The consensus of development experts was that "good advisers and technical experts would formulate good policies, which good governments would then implement for the good of society" (World Bank 1997, p. 1).

The socialist mentality and the vision of state-led development were so ingrained that as late as 1985, after years of failure, Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi could write,

THE REVOLUTION IN DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS

THE REVOLUTION IN DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS