Contents

KINGDOM of NAUVOO

THE RISE AND FALL OF A RELIGIOUS EMPIRE ON

THE AMERICAN FRONTIER

BENJAMIN E. PARK

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

ALSO BY BENJAMIN E. PARK

American Nationalisms:

Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions, 17831833

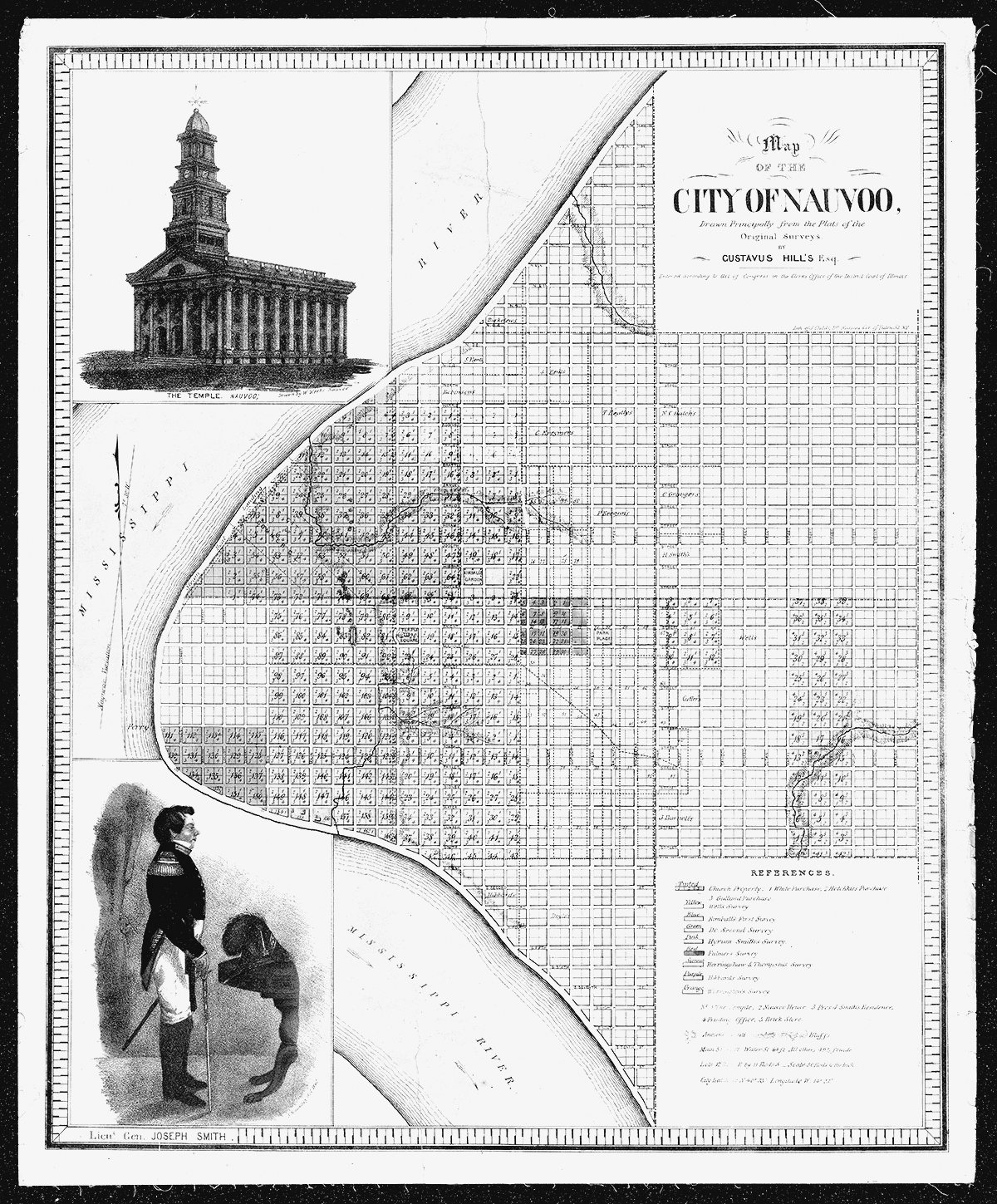

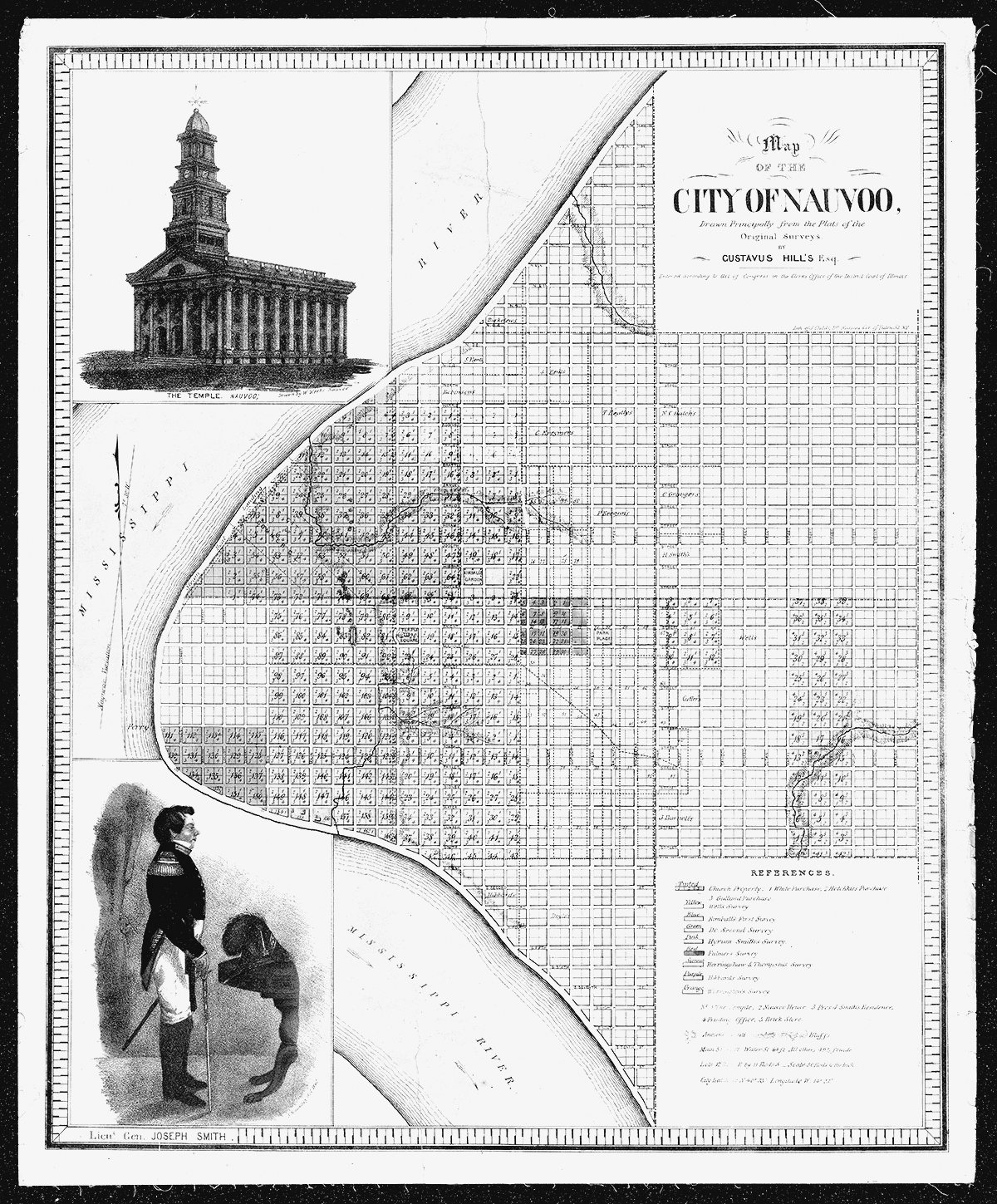

Gustavus Hills, draftsman, J. Childs, lithographer, Map of the City of Nauvoo, with insets of architectural rendering of the Nauvoo Temple and Joseph Smith, Lieutenant General of the Nauvoo Battalion, 1844, based on materials provided in 1842. LDS CHURCH HISTORY LIBRARY, SALT LAKE CITY.

There is a natural inclination in mankind for a kingly government.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, 1787

William Major, painting of Joseph Smith and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Nauvoo, Illinois, 1845. From left to right, the painting depicts Hyrum Smith, Willard Richards, Joseph Smith, Orson Pratt, Parley P. Pratt, Orson Hyde, Heber C. Kimball, and Brigham Young. All of these men also participated in the Council of Fifty around this same time. LDS CHURCH HISTORY LIBRARY, SALT LAKE CITY.

The clandestine council gathered two days later, where its members breathlessly discussed a new founding document for their divine government, one that would replace the US Constitution. A committee composed of a handful of men had been toiling for weeks to draft the text, and the rest of the council was eager to see the finished product. They were not disappointed. We, the people of the Kingdom of God, the document began, borrowing from the text they were seeking to supplant. What followed was a paradoxical mix of traditional republican language and revolutionary theocratic ideas. It was time, the document announced, for the kingdom of God to replace the governments of men. The men who crowded around to hear the constitution read out loud for the first time readily acknowledged the significance of the moment. They were at the cusp of a new form of divine governance.

Though the proposed Mormon constitution was incomplete and required further revision, the delegates could hardly contain their excitement. One remarked that it was the greatest day of his life, and another noted that they were treading on holy ground. After the festivities were over, William Clayton, who served as the councils

The men reviewing the document, informally known as the Council of Fifty, were part of one of the most radical religious and political endeavors of the American nineteenth century. They rejected Americas democratic system as a failed experiment and sought to replace it with a theocratic kingdom. A new Mormon empire, they believed, was the only thing that could restore stability and justice to a fallen world. Democracy was a misguided effort that had run its course, and they were ready to offer a correction.

The detailed minutes from the councils meetingsmeticulously recorded by a secretary, Clayton, who was convinced that their proceedings held the key to the worlds futurewere restricted from believers and historians alike for 172 years, even as rumors of their scandalous contents spread both within and beyond the faiths community. Finally, in 2016, the Latter-day Saint church allowed their release and publication, the culmination of several years of increasingly generous decisions by the church to grant access to its voluminous historical collections. The availability of these extraordinary sources, and the release of many other Mormon documents from the 1840s, has finally made it possible to offer a full-scale account of a significant and revealingyet largely forgottenmoment in American history.

THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS has often been seen as an anomaly in America. Joseph Smiths claims of deific visions, angelic visitations, and gold plates, not to mention the now-abandoned practice of polygamy, have made Mormonism an easy object of ridicule as much as a serious topic for study. The Broadway musical The Book of Mormon mixes mockery with sincere interest, yet still highlights the cultural chasm between the church and its surrounding culture. The Mormons, for their part, have often contributed to this view, through their insistence on exceptionalism and uniqueness.

To the extent that modern Mormonism is accepted in contemporary America, it is largely due to Mormons ability to keep quiet about their distinctive beliefs and practices. Mitt Romney won the Republican Party nomination for president in 2012 by downplaying his faith and emphasizing Mormonisms common ground with evangelicals. Indeed, the Latter-day Saint churchs conservative principles on gender and marriage have been a way to build solidarity with the religious right. In a pragmatic alliance that has allowed Mormons a space in the public sphere, both the church and the nation have agreed to overlook a long history of animosity and conflict. As evidence of this continued assimilation, church leaders in 2018 announced their intention to retire the term Mormon as a way to, among other things, close the gap between themselves and other Christians and distance the faith from its past identity.

Yet while they have often been seen, and have frequently seen themselves, as outsiders, Joseph Smith, his followers, and their church were, in the first instance, products of their nation and times. Along with other marginalized groups that drew the ire of the white Protestant mainstream, like Catholics and Shakersthough not nearly as severe a backlash as African American congregations and numerous indigenous tribesthe Mormons constituted a minority group that fought, and often failed, to enjoy the protections and benefits supposedly guaranteed by the US Constitution. Far from a cult on the margins of American life, they challenged other Americans to live their ideals: whatever the Constitution might say, how, in practice, could a nation of diverse peoples and faiths hold together?

The Mormon challenge was rooted in the short-lived city of Nauvoo, founded by Joseph Smith in 1839 in Illinois, on the banks of the Mississippi River. Nauvoo was the crucible of the Mormon experiencethe episode that saw their prophet murdered and their dreams of a religious empire dashed. If the Mormons are poorly understood by most Americans, Nauvoo is virtually unknown. To Mormons, it remains an important site. It shapes how they think about their traditions past, and persists as a pilgrimage destination: hundreds of thousands stream into the small town every summer to watch plays, tour historic homes, play games, and take in speeches by experienced missionaries. The faithful see Nauvoo as a monument to their spiritual ancestors and beloved prophet, Joseph Smith. But to the rest of the country, the city is, at best, an exotic name, a historical oddity overshadowed by Illinoiss veneration of its adopted son, Abraham Lincoln.

Historians know more about the Mormons and Nauvoo, but their view is a partial one. Very few histories of Nauvoo have been written for a general audience in the last fifty years, and the existing treatments have serious limits, especially when they argue, as they often do, that Mormonism diverged from American culture and society. Smiths theocratic bent seems incongruous in a period supposedly characterized by the expansion of democracy, and his emphasis on priesthood authority appears to clash with prevailing beliefs in individual freedom and social mobility. Yet while the Jacksonian era was one of democratic upheaval, it also provoked a cultural backlash. To many people, not just the Mormons, American society seemed to be spinning out of control. Early Mormonisms radical solutions were designed to solve problems many non-Mormons also perceived. Indeed, their success at winning converts stemmed from their ability to tap into widespread sentiments about social decay and failure.

Next page