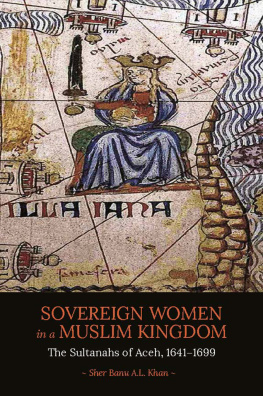

Sher Banu A. L. Khan - Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699

Here you can read online Sher Banu A. L. Khan - Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book is dedicated to the women of Aceh Dar al-Salam:

May you draw courage and inspiration from your own history.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude and thanks to the following institutions and people who have helped me throughout my journey to complete this book.

To the people who formed the backbone of my book. My deepest gratitude goes to Emeritus Professor Anthony Reid, who is the inspiration for this book, who first introduced me to the world of Aceh and women in pre-colonial Southeast Asia, for his generosity in sharing his ideas and the continual discussions we have had over many years, across different places and time zones. To Professor Dr Leonard Bluss, for his unfailing support and faith in me. To Professor Dr Jan van der Putten, who generously spent many hours of his time with me deciphering the intricacies of Old Dutch. To Dr Ito Takeshi, for granting access to his invaluable transliterations of VOC materials, and his research on Aceh. The VOC materials are now published in Aceh Sultanate: State, Society, Religion and Trade: The Dutch Sources, 16361661 in two volumes (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2015). To Professor Felipe Fernndez-Armesto, for his support and patience.

I am indebted to the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters, Queen Mary University of London and University of London Postgraduate Research Studentship funding which I received from 2004 to 2007. I am grateful to Universities UK for giving me the Overseas Research Students Award. I am thankful to the organisers of the TANAP (Towards an Age of Partnership) programme, Leiden University, in particular to Professor Leonard Bluss, for supporting my Advanced Master of Arts. My thanks also go to my current university, the National University of Singapore, for granting me the start-up funding and for a semesters writing leave.

I extend my utmost appreciation to all the staff in the various institutions and libraries, generously extending their help, who went beyond the call of duty to help me locate materials and resources for my research. I thank all my friends in the Netherlands, at Leiden University, Universiteit Bibliotheek, KITLV and Nationaal Archief. In the United Kingdom, the British Library. My friends in Aceh at the Pusat Dokumentasi dan Informasi Aceh, Yayasan Hasjmy and Museum Aceh. In Kuala Lumpur, at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia and Perpustakaan Negara. In Jakarta, at Arsip Negara and KITLV Jakarta. Special thanks to Paul Kratoska and Lena Qua at NUS Press, Singapore, and Emma Coupland for her expert copyediting. Last but not least my former institution, the National Institute of Education and Nanyang Technological University.

I thank all the generous scholars who have shared their expertise, thoughts and materials with me, namely Peter Borschberg, Radin Fernando, Geoff Wade, Annabel Teh Gallop, Michael Laffan, Leonard and Barbara Andaya, and the late Professors Dr Ali Hasymi, Dr Ibrahim Alfian and Dr Teuku Iskandar.

My deepest appreciation goes to my friends, colleagues and all the well-wishers I have met in the course of my research and writing this book. To Associate Professor Noor Aisha, head of the Malay Studies Department at the National University of Singapore, whose support I truly value, and to Professor Malcolm Murfett, for his concern and constant advice. Those who extended their generosity and hospitality, opening their homes to make me feel welcome when I was away from home, especially Professor Salleh Yaapar and his wife Kak Timah while they were in Leiden, Brother Feng and Anna in Leiden, the late Ami Farouk and Amati in Amsterdam, and Bhai Khaled and Kak Safiah in Dulwich, London. To my other friends, Cynthia and Marijke at Leiden University, Rosemary at KITLV, Roksana at the National Institute of Education, Saira Begum in Johor Baru and Kak Zunaima in Aceh.

I am especially beholden to my family for bearing with me on the long journey towards the completion of this book. My thanks to my parents, Abdul Latiff Khan and Noorjan, my in-laws, Abdul Rahim and Sapiah, for their supplications, my sister, Shahmim Banu, who has kept my spirits high and, most of all, my gratitude goes to my husband, Aidi, who has stood by me throughout this undertaking.

May God bless all who have helped me in one way or another, and for those whose names I may have inadvertently overlooked, thank you!

Preface

The remarkable fact that a succession of not one but four women rulers of the sultanate of Aceh Dar al-Salam in the second half of the seventeenth century has remained largely inexplicable spurred me to undertake an in-depth investigation to explain this phenomenon. Women sovereigns ruling Muslim kingdoms are few and far between, and usually unknown. Fatima Mernissis book, The Forgotten Queens of Islam, attempted to rescue and to recognise them in history. However, even Mernissi had forgotten the numerous Muslim queens in Southeast Asia, despite the fact thatbesides the sultanahs of Acehthere were indeed many other Muslim queens in Patani, Sukadana, Bone, Jambi, among others. One possible reason for this neglect is the lack of records these women left, compared to the letters and diaries of European queens, and the lack of indigenous records about these Muslim queens in Southeast Asia.

To undertake such a study, one must rely on the European records to supplement the indigenous ones. In the course of the seventeenth century, the Dutch and English East Indies Companies recorded the histories of the individual Malay polities they encountered. These are the most voluminous and invaluable recordsespecially from the Dutch as they were the most dedicated recordersand these are largely intact in the Nationaal Archief in The Hague. Although these sources are available, they are not accessible to those who do not know Dutch, especially classic Dutch, and are unable to read the beautifully written manuscripts by official scribes, illegible to the untrained eye. It took me about a year of intensive training in Old Dutch and palaeography under the TANAP programme at Leiden University before I could transliterate, translate and glean information from these records.

In the course of mining the Dutch and English company records, I was struck by the detailed reports of the company officials relating the vivid happenings at the Aceh court and was intrigued by the role the queens played, especially Sultanah Safiatuddin. The narratives gleaned from these sources not only enabled me to reconstruct a more detailed picture of the reigns of these queens but continue and deepen the conversation begun by earlier scholars. New evidence has allowed me to demonstrate that these women rulers were not mere puppets but ruled in their own right, albeit with serious challenges. Sultanah Safiatuddin nearly lost her life defending her honour when she was accused of committing adultery with an ulama (a religious scholar). The detailed narratives reveal interesting aspects of the queens relations with her male elite (orang kaya) and the foreign envoys, and provide a more nuanced picture of royal-elite relations under female rule, where power was more fluid and contested rather than reflecting the view that power mainly tilted towards the male elite. I gained considerable insight into the male elite and demonstrate that there were many factions among them and much intrigue as they vied for power. The detailed information even described the personal relations between the Dutch, the English and the Acehnese male elite, considerably enriching the narratives, and showed that these personal relations mattered in the bigger scheme of politics and diplomacy, and the contestations for power.

However, one of the difficulties I faced in writing this book was how much of the rich narratives I should leave outgiven the word limits of a book publicationwithout sterilising the narratives, while allowing enough space for my own observations and analysis. In the end, I adopted both a descriptive and an analytical approach. In Chapters 2, 3 and 4, the descriptive narrative illuminates the intimate, at times, emotional relations between the Acehnese elite and the company officials, and the rich discussionseven the dance Commissar Vlamingh had to perform for Safiatuddinreported from audience days that determined how events unfolded and the actions both powers took. The other chapters provide the analytical perspective, explaining why a woman ruler was crowned for the first time in Aceh in 1641 when Southeast Asia was experiencing what Anthony Reid termed as the age of commerce, and why female rule was accepted for 59 years in a Muslim kingdom when it seemed an anathema to Islam. The analysis revisits the notion of the

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699»

Look at similar books to Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sovereign women in a Muslim kingdom : the sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.