Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260

Copyright 2017, University of Pittsburgh Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 13: 978-0-8229-6491-9

ISBN 10: 0-8229-6491-0

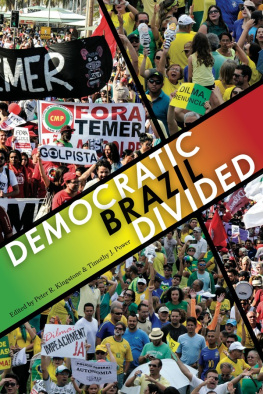

Cover art: Manifestao by Geraldo Magela/Agncia Senado is licensed under CC BY 2.0; #ForaTemerOlimpico by Flickr user IdeasGraves is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Cover design: Joel W. Coggins

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-8290-6 (electronic)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SOME POLITICAL EVENTS happen so suddenly and unexpectedly they shake up much of what we believed to be true. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the Arab Spring both revealed the profound weakness of regimes believed to be much more durable and overturned years or even decades of social science wisdom. Brazils rapid rise from feckless democracy to BRIC and back again is perhaps not as surprising or as disruptive of social science and public wisdom. But it is in the neighborhood.

The simplest way to illustrate the speed of change for us is to chart how our effort to organize, frame, and name this volume changed over the course of the project. When in 2013 we first assembled the contributors to comment on the state of democracy in Brazil, the proposed title of the future volume was Democratic Brazil Ascendanta testament to Brazils stability and global leadership and example for developing countries everywhere, including the coining of the term the Braslia Consensus as a contrast to the much criticized Washington Consensus. The Vinegar Revolution protests of June 2013 had not yet broken out in So Paulo, but then again, nobody predicted this massive wave of demonstrations either. With mounting evidence of economic malaise, social unrest, and corruption, we spent much of 2013 and 2014 wondering whether we were witnessing the exhaustion of a virtuous cycle. Would the ruling Workers Party (PT), which presided over an impressive period of social inclusion after 2003, be able to hold on to power? Was this the end of an era? Dilma Rousseffs reelection in October 2014 should have provided an answer, but in reality it provided only a fleeting veneer of stability, which proved illusory just months later. In 2015 charges of budgetary crimes and the impeachment process brought the PTs dominance of politics to an end and revealed a high level of polarization and anger as Brazilians divided against themselves. Thus, the final name of the volume, Democratic Brazil Divided. We moved from a framing device of ascendance to one of division in only two years.

For our Brazilian colleagues and friends, this period has been painful and has divided friendships, institutions, and even professional associations. For those brasilianistas like ourselves, Brazils sharpening polarization evokes an unwelcome sense of dj vu. The first Democratic Brazil involved a group of young United Statesbased political scientists who had all begun their doctoral research work shortly after the restoration of democracy. We saw ourselves as a distinctive cohort who had no experience of authoritarian Brazil and believed that this lent the volume a cohesive viewpoint. The Brazil we came to know in our research was indeed volatilepolitically and economically. Our more senior colleagues, Brazilian and non-Brazilian, coined a wide variety of phrases to capture the apparent chaos of the late 1980s and early 1990s (including the term above, feckless democracy). Public opinion polls and many scholarly analyses suggested that Brazil was the Latin American laggard in consolidation of democracy.

The twenty-first century, then, brought great satisfaction. Brazil was still a moving target, but we were now charting the important ways in which democracy was indisputably deepening. Both of our earlier volumes capture this sense of progress even amidst great challenges. Indeed, a very important strand of political science literature, driven by leading Brazilian scholars, argued that the political system had always been more governable than critics imagined. This Brazil rested on a functional and even effective form of coalitional presidentialism that brought economic stability and then prosperity, generated and diffused world-leading social policy innovations, and became a regional leader and an emergent global power on the basis of these achievements.

The return of crisiseconomic and politicalhas terrible human consequences, and the circular sense of returning to our starting point as observers of Brazil is disheartening. Yet, beneath the tensions of the moment, we retain the awareness of great strides and of people dedicated to making the country a more democratic, prosperous, and just society. The current volume in the Democratic Brazil series refers to a nation divided, but with the hope that the next iteration returns to celebrating a forward trajectory.

As with the first two volumes of this series, the project began as a series of panels and public presentations. Earlier collaborations took advantage of the annual conferences of the Latin American Studies Association. This iteration benefited instead from the fortuitous fact of Peter Kingstones decision to follow Timothy Power to the United Kingdom in the summer of 2012. Tim had moved to Oxford in 2006, and for the first time in our careers, we found ourselves within a short distance of each other. The result was a two-day conference involving all the contributors, the first day at Kings College London (KCL) and the next day at Oxford. The resulting volume benefited as a result from the lively comments and questions from the knowledgeable and diverse London and Oxford based audiences, including academics, policy makers, diplomats, journalists, and businesspeople. We were also very fortunate to have comments from outstanding discussants drawn from our colleagues and visitors at the two institutions. Leslie Bethell, Olivier Dabne, Mahrukh Doctor, Anthony Hall, Leigh Payne, Miriam Saraiva, Matias Spektor, and Laurence Whitehead all served as chairs and discussants and greatly contributed to the quality of the papers.

We are grateful to Kings College London, the University of Oxford, and Santander Universities UK for financial and logistic support for the conference. But the challenging task of managing a conference over two days in two cities at two universities depended on the flawless coordination of David Robinson of the Latin American Centre (LAC) at Oxford, Jacqueline Armit of Kings Brazil Institute, and Flo Austin of Kings Department of International Development. We are indebted to Alison Walsh, a graduate student at Oxfords Latin American Centre, who prepared the final manuscript for publication. Finally, we are grateful to Peter Kracht and Josh Shanholtzer for their enthusiastic support for the ongoing Democratic Brazil enterprise and their patience as this volume made repeated changes to respond to the rapidly changing landscape of Brazilian democracy.

Peter Kingstone would like to thank KCLs Department of International Development for its support. Tim Power is grateful to the Latin American Centre and to its parent department at Oxford, the School of Interdisciplinary Area Studies.

Finally, as in all our endeavors, we would like to thank our families, Lisa, Ben, and Lara Kingstone and Valria Carvalho Power, for their unflagging love and support.