2016 Georgetown University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

9781626166424 pbk 2018 Georgetown University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miller, Paul D., author.

Title: American power and liberal order : grand strategy in the 21st century / Paul D. Miller.

Description: Washington, D.C. : Georgetown University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016019988 (print) | LCCN 2016024344 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626163423 (hc : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781626163430 (eb)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesForeign relations21st century. | Security, International. | National securityUnited States.

Classification: LCC JZ1480 .M553 2016 (print) | LCC JZ1480 (ebook) | DDC 327.73dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016019988

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

19 189 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 First printing

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design by Jen Huppert.

PREFACE TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION

I frame the central debates in this book as, first, between internationalism and restraint or retrenchment, and, second, between liberal and conservative versions of internationalism. The first debate is the most interesting point of difference among international relations scholars since the end of the Cold War; the second is a more consequential debate among practitioners about how best to implement the bipartisan internationalist consensus that has held since 1945. The first debate is almost purely academic; few policymakers have taken restraint very seriouslyalthough, as I argue in the book, the Obama administration blended liberal internationalist rhetoric with an instinct for restraint reflected in budgetary and deployment decisions.

With impeccable timing, I published this book in August 2016, just before the presidency of Donald J. Trumpand, more so, the nationalist Jacksonian movement to which he has given voiceintroduced new dimensions and complications to these debates. Trumps election and first two years in office have shifted the debate on Americas role in the world. It is no longer only a debate between restraint and engagement or between conservative and liberal versions of internationalism. It is also a debate between nationalism and internationalism. Interestingly, conservative and liberal internationalists have key beliefs in common that differ in crucial ways from nationalism.

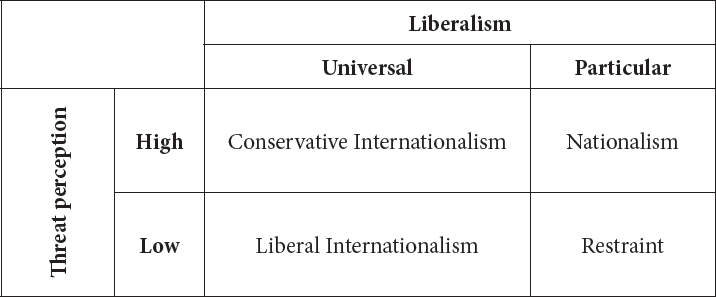

The paperback edition of this book, coming two years into the Trump presidency, is an ideal opportunity to address Trumps record and the nationalist phenomenon he leads. (I address these questions exclusively in this preface; the main body of the book has not been revised.) I suggest we map the terrain by asking two foundational questions. The first and most important is about the ontological status of liberalism and about Americas role in the world. Is liberalism universalizeable, and America its champion? Or is liberalism just another tribal practice, and America has no particular interest in its fate beyond our shores? The second asks, How dangerous is the world? The answer correlates with ones beliefs about the costs of foreign policy initiatives, the relative utility of hard power versus soft power, and the viability of cooperation. At one end of the spectrum are those who think the world is very dangerous, action is difficult, military power is more dependable than

Figure P.1. Grand Strategic Options for the United States

This book weighs the pros and cons of conservative internationalism, liberal internationalism, and restraint, coming out in favor of the first. But the return of American nationalism to the forefront of public debate raises important questions: what is American nationalism, where does it come from, what does it advocate, and how does it differ from, or overlap with, a conservative internationalist approach?

Nationalism and Liberalism

The most important difference between nationalists and internationalists (both conservative and liberal) is that nationalists believe liberal values are not universal, that they cannot find root elsewhere in the world (or, if they can, it is anyway irrelevant), and that the United States should not make their spread part of its foreign policy. As Samuel Huntington argues, the West is unique, not universal. Its ideals are not shared or even admired much elsewhere in the world, in Huntingtons viewand it is foolish, dangerous utopianism to think otherwise.

Trump gave voice to this viewpoint when he claimed in his foreign policy campaign speech in 2016 that American foreign policy began to go wrong with a dangerous idea that we could make western democracies out of countries that had no experience or interests in becoming a western democracy. The effort to foster, champion, or encourage liberalism goes against the tide of history, culture, identity, and civilization, in this view, and it is doomed to founder, as proven by wasteful adventures in Vietnam and Iraq.

Similarly, Trump said in Warsaw in 2017 that our freedom, our civilization, and our survival depend on these bonds of history, culture, and memory.

This line of thinking is solidly in the tradition of thinkers like Edmund Burke, Alexis de Tocqueville, and even Georg Hegel, insofar as these thinkers stressed the cultural and especially religious underpinnings of a regimes characteristics. Hegel, in particular, was keen on divining the national spirits that animated and defined different peoples and suited them to particular forms of government and society. Liberalism is the tribal habit of Western peoples, the received practice of Western history, in this view. We value it because it is ours, not because it possesses intrinsic, transcultural merit. This view is not necessarily extreme: it is reasonable to believe that liberalism is uniquely Western because European thinkers originally explicated its philosophical justifications and most of its institutions first appeared in European nations.

But the intellectual lineage of this view does not make it correct. Trumps view is historically and culturally deterministic, and the facts do not support his determinism. The history of the relationship between liberalism and Western history is just that: history. It is not a deterministic blueprint for the future of liberalism or its prospects outside the West. Non-Western liberalism exists: it is demonstrably possible to have a democracy in a place that did not experience Western history or produce Enlightenment philosophers.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.