Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC 20002

http://gupress.gallaudet.edu

2002 by Gallaudet University

All rights reserved. Published 2002

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

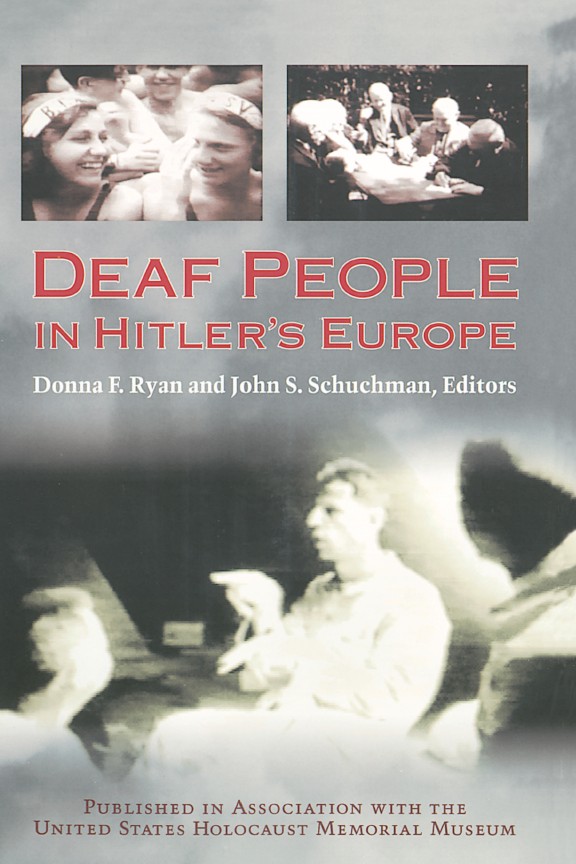

Deaf people in Hitler's Europe / Donna F. Ryan and John S. Schuchman, editors.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-56368-132-3 (soft cover: alk. paper)ISBN 1-56368-126-9 (alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-56368-201-8 (electronic)

1. DeafGermanyHistory20th century. 2. DeafGovernment policyGermany. 3. DeafEuropeHistory20th century. 4. HandicappedGovernment policyGermany. 5. EugenicsGermanyHistory20th century.

I. Ryan, Donna F. II. Schuchman, John S., 1938-

HV2746.D43 2002

940.53'18'0872dc21 2002073884

The assertions, arguments, and conclusions contained herein are those of the volume editors or other contributors. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Cover images from the film Verkannte Menschen (Misjudged People). Used by permission of Landesverband der Gehrlosen Hessen e.V., Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Design and composition: Alcorn Publication Design

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

Preface

Donna F. Ryan

The following collection of essays is the result of several threads of investigation and scholarship woven together at the Deaf People in Hitler's Europe, 19331945 international conference, which took place in Washington, D.C., on June 2124, 1998, under the auspices of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the History and Government Department at Gallaudet University.

The research that led to the conference began when the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum opened in April 1993. The Honors Program at Gallaudet University instituted a special interdisciplinary seminar about the Holocaust to coincide with the opening of the museum. Students in the course, taught by Jane Hurst of the Department of Philosophy and Religion and me, struggled to grasp the enormity of the horror by reading historical, literary, and philosophical texts and by visiting the permanent exhibition at the museum. Toward the end of the semester, Lilly Shirey, a deaf Jewish woman who fled Vienna in 1940 with her deaf mother and sister, came to speak to the class. She had been very young at the time of her escape from Austria, but her retelling of her family history touched students deeply. They understood how imperiled they might have been had they lived in Vienna in 1940, the year that forced sterilization policies were imposed in Austria. Survivor stories are always powerful, but the unique experiences of this family, whose escape was complicated by special difficulties dealing with the authorities, had extraordinary meaning for this class of deaf college students.

The reaction from students led to the collaboration that brought about this project. John S. Schuchman, the son of deaf parents and an expert in deaf community history and videotaped historical interviews with deaf people, agreed to work with me because of my research expertise on the Holocaust. We set out to discover how much research had been done about the deaf experience in Europe during World War II and committed ourselves to trying to get this story the attention it deserved. We hoped to collect extant videotaped interviews with deaf informants and supplement them with new interviews. We learned quickly that the professional oral historians and the deaf community oral historians had little knowledge of or contact with each other. The videotaped interviews with deaf informants at the Fortunoff Archive at Yale University, the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum were conducted carefully by historians who were experts on the Holocaust but who had little knowledge of the deaf community and who usually had to depend on sign language interpreters to communicate. The videotapes of community historians such as Jochen Muhs and Simon Carmel filled in many of those gaps, for the interviewers, themselves members of the deaf community, had the confidence of their informants and the knowledge to pose questions about the experiences of deaf people during the 1930s, including some very sensitive questions about sterilization and the existence of deaf Nazis. But these videotapes were made by individuals working out of their homes and their own pockets, without the benefits that the large oral history projects enjoyed. We hoped to bring these two worlds together to encourage an exchange of information and collaboration.

Between 1993 and 1997, John Schuchman and I undertook several research and speaking trips to Germany, France, Great Britain, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, the Netherlands, Norway, Canada, and several cities in the United States. We learned more about the work of Horst Biesold, a teacher of deaf children whose groundbreaking interviews with deaf German victims of forced sterilization, published in English as Crying Hands, is the most authoritative work on the subject to date. Likewise, the work of Jochen Muhs began to highlight the many ways deaf people responded to the dramatic events unfolding around them. Gerhardt Schatzdorfer and Francine Gaudry, producers of the Bayerischer Rundfunk program for the deaf community, Sehen statt Hren, were kind enough to share their complete footage of interviews for a special segment on deaf Jewish Holocaust survivors living at the Helen Keller Institute in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Several conferences at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Research Institute focused on the activities of doctors and other medical professionals in the Third Reich. They also brought together researchers in the forefront of Holocaust scholarship, including Henry Friedlander, Robert Proctor, Benno Mller-Hill, Gisela Bock, and Patricia Heberer, all of whose work is central to the story of the treatment of people with disabilities, even though they do not focus on deaf people as a separate group. Moreover, the resources of the museum, from the archives and library to its ever-helpful staff, have been of immeasurable help in pulling together this story.

Henry Florsheim, Ruth Stern, Eugene Bergman, David Bloch, and Harry Dunai are among the deaf survivors living in the United States who shared their stories. During our 1997 trip to Hungary, we encountered twelve survivors in Budapest who were willing to share their harrowing and heroic experiences when the Germans arrived in March 1944. After meeting them it was clear that we had to bring together as many of the researchers and survivors as possible. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum agreed that this was a story that needed to be elucidated and told.

The conference included formal academic presentations as well as witness panels, a screening of the 1932 film Verkannte Menschen (Misjudged People), an opportunity for deaf Europeans to formally join the Survivors' Registry at the museum, and a moving ecumenical memorial service for deaf Holocaust victims conducted by Fred Friedman, a deaf rabbi, in the Hall of Witness.

After the conference, it seemed appropriate to publish some of the presentations. For formal spoken English-language papers, the task was simple. But many of the presentations were made in spoken German, German Sign Language, American Sign Language, and Hungarian Sign Language. Moreover, some of the most eloquent and touching moments came during the survivor testimonies. Such panels are not formal presentations and, in this case, there were several sign languages involved, making translation that maintains the tenor of the moment difficult. We have decided to incorporate the testimony in a narrative historical form, as an essay by John Schuchman. A transcript of segments of the interviews appears in the appendix, so that the survivors can also tell their own stories.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.