Nietzsches Political Skepticism

Nietzsches Political Skepticism

Tamsin Shaw

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2007 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shaw, Tamsin, 1970

Nietzsches political skepticism / Tamsin Shaw.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-1-40082-812-8

1. Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, 18441900Political and social views. 2. Legitimacy of

governments. 3. Authority. I. Title.

JC233.N52S43 2007

320.01dc22 2007018560

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my parents, Robin and Kate Shaw

Abbreviations

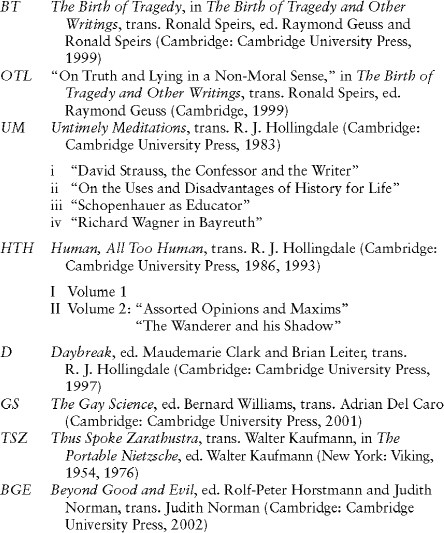

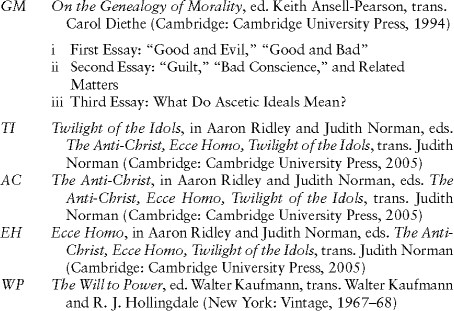

I have used the abbreviations below for Nietzsches works. I have cited the translations listed with some modifications. I have used the Werke:kritische Gesamtausgabe, edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinar, (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1967), which, where cited, I have abbreviated to KGW followed by volume and page number.

In citing Schopenhauer I have used E.F.J. Paynes translation of The Worldas Will and Representation, 2 vols. (New York: Dover, 1958, 1969), which is abbreviated to WWR, followed by volume and page number.

Nietzsches Political Skepticism

Introduction

Without the assistance of priests, no power can become legitimate even today.

Human, All Too Human, I, 472

Nietzsche is a frustrating figure for political theorists. Those who take seriously his insights into morality, culture, and religion have often been struck by the fact that he abstains from developing these insights into a coherent theory of politics. There are two ways in which we might nevertheless try to derive a political theory from his work.

One way would be to uncover an implicit theory underlying his avowed political views. This route has not been widely held to hold much promise. He does, of course, indulge in some strident criticisms of nave or decadent political ideals. But these have often been simply dismissed as being churlish rather than profound.

The other way would be to spell out the political implications of his broader philosophical views. These might be seen to be compatible with his political opinions.

In this book, I would like to defend the view that Nietzsche indeed fails to articulate any positive, normative political theory. It is tempting to assume that there are only uninteresting reasons (lack of understanding, lack of interest, unreflective parochialism) for this failing. But I want to make a case for the claim that there is an interesting reason. I shall argue that, in his early and middle works in particular, Nietzsche articulates a deep political skepticism that can best be described as a skepticism about legitimacy.

In using the term political skepticism, I am not alluding to the established positions that generally go by that name in the Anglophone tradition, such as those associated with Michael Oakeshott and Isaiah Berlin. The former involves a claim about the limitations of technical expertise in politics; Nietzsche, I shall argue, is less concerned with the conflicts that arise when we try to realize our values in political life than with our inability to arrive at a form of politics that is genuinely grounded in normative authority.

His guiding political vision, I shall claim, is oriented around the rise of modern state, which requires normative consensus in order to rule, and a simultaneous process of secularization that seems to make uncoerced consensus impossible. The state has the ideological capacity to manufacture this consensus but no necessary concern that it should involve convergence around the right (as opposed to merely politically expedient) norms.

Nietzsche doubts that secular societies can otherwise generate sufficient consensus. They therefore lack any reliable mechanism for placing real normative constraints on state power. But, I shall argue, he does not want to give up either on the possibility of having stable political authority or on his commitment to an independent source of normative authority. So his political skepticism derives from the fact that he holds both to be necessary but cannot see how they can be compatible.

To many of Nietzsches readers, no doubt, it will sound as though this kind of political skepticism presupposes precisely the kind of normative realism that he has been widely taken to reject. Any interpreter of Nietzsche must face a tricky problem concerning the status of his evaluative claims, particularly in the later works. The anti-objectivist meta-ethics that is suggested there seems to be in conflict with the objectivist-sounding evaluative judgments that he defends. Some interpreters claim that there are readings that can render these aspects of his work compatible, in particular by refusing to take the value judgments at face value. Nietzsche does not mean them, they claim, to express objective normative truths. I shall defend the view that the evidence is mixed, but that the incompatibility thesis provides us with a more plausible and coherent account, as well as one that can help us to make sense of this interesting political dilemma.

If we read Nietzsche, at least in his later period, as a consistent antirealist, we will still encounter a version of the political problem that I have described, concerning an inability to formulate a coherent conception of political legitimacy. On an antirealist view of the status of his own values, Nietzsche must not only lack a normative political theory that can be justified to others, but will also (as we shall see in chapter 4) lack a coherent conception of how his own values might ground political authority.

But even if we take Nietzsches value-criticism to be objectivist in orientation, that is, if we read him as a moral realist, we will arrive (perhaps more surprisingly) at an antitheoretical view of politics. And on this reading we can make sense of the distinctive form of political skepticism that he discovers.

As I have already indicated, there are many different ways in which we might try to assess Nietzsches contribution to political thinking. I do not myself believe that the political skepticism that I am attributing to him will provide an interpretive framework that renders coherent every aspect of his thought, or one that is compatible with all the diverse philosophical and political claims that he makes. But I hope to show that it is at least a sufficiently distinctive and interesting strand in his work to merit examination in its own right.